The lengthy gestation period in preproduction on The Wizard of Oz is a textbook example of the intrinsic collaborative efforts that cumulatively functioned under the studio system during its glory days. Whether contemplating the lush costumes created by resident fashion guru Gilbert Adrian or the intricate makeup applications developed under Jack Dawn, MGM’s supremacy in the industry and its veritable and diverse army of artisans and craftsman practically guaranteed that Frank L. Baum’s novel would receive meticulous attention to every last detail.

This assessment of Metro’s formidable stock company by no means suggests that the incubation of Oz on celluloid was either a foregone, direct or finite conclusion. On the contrary, The Wizard of Oz had one of the most arduous, stagnated and demanding production schedules of any motion picture before or since its time.

In truth, studio mogul, Louis B. Mayer had not desired to translate The Wizard of Oz to film. Recognizing the enormity of its undertaking, and the unsteady appeal of what had already been done on celluloid, Mayer resisted the idea for as long as he could. His apprehensions were well founded. Previous attempts at casting humans as fantasy creatures in adaptations of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (1933) and Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935) has been costly box office failures.

The genesis of Oz on film derived from a trajectory of interests. As early as 1937, Arthur Freed had expressed his to Mayer. A successful songwriter by 1938, Freed had recently been elevated to the stature of fledgling producer – a move that bode well with Freed’s aspirations to remake relative unknown Judy Garland a musical star. Although Freed had written many of the standards in pop music of his generation, as a producer his bankable box office had yet to be proven.

In his attempts to gain Mayer’s acceptance, Freed repeatedly pointed to the financial and critical accolades reaped by Walt Disney on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) – a project not unlike Oz that had begun with overwhelming critical backlash from the press, who had dubbed the project in its infancy as ‘Disney’s folly.’ Enter Mervyn LeRoy – a quantifiable producer that Mayer had wooed away from Warner Brothers.

When asked by Mayer what projects he would consider, LeRoy pitched The Wizard of Oz. The rest of the details in Oz’s early gestation are a bit sketchy, even after considering interoffice memos. Ultimately, Mayer relented. MGM vice-president Eddie Mannix acquired the rights from Samuel Goldwyn on February 18, 1938 and the project progressed. LeRoy assumed producer responsibilities with Arthur Freed as his unaccredited assistant.

The early development of narrative concepts for Oz contains some interesting anomalies. Arthur Freed

concocted two original characters not in Baum’s books the operatic ‘Princess of Oz’ and laconic Prince. Possibly, the former was in deference to preliminary suggestions by Loew’s President Nicholas Schenck, that Deanna Durbin should be considered for the part of Dorothy. The latter was clearly a joint venture between Arthur Freed and Mervyn LeRoy, both ambitious to launch the career of their protégée, MGM contract player, Kenny Baker.

concocted two original characters not in Baum’s books the operatic ‘Princess of Oz’ and laconic Prince. Possibly, the former was in deference to preliminary suggestions by Loew’s President Nicholas Schenck, that Deanna Durbin should be considered for the part of Dorothy. The latter was clearly a joint venture between Arthur Freed and Mervyn LeRoy, both ambitious to launch the career of their protégée, MGM contract player, Kenny Baker.Schenck also orchestrated a meeting with Fox President Darryl F. Zanuck to discuss the possibility of a loan out of Shirley Temple for the role. Although ill-equipped

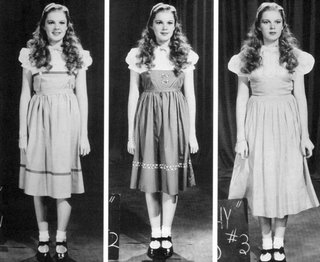

musically to handle the demands of Dorothy, Temple was much closer in age to Baum’s heroine as written than Judy Garland. While Freed worked behind the scenes to deflate these alternative choices for the lead and plump up Garland’s acceptance, the rest of the cast was beginning to take shape.

musically to handle the demands of Dorothy, Temple was much closer in age to Baum’s heroine as written than Judy Garland. While Freed worked behind the scenes to deflate these alternative choices for the lead and plump up Garland’s acceptance, the rest of the cast was beginning to take shape.The initial mismatching of Vaudevillians Ray Bolger as the Tin Man and Buddy Ebsen as the Scarecrow was remedied during preliminary talks in which an impassioned Bolger pleaded with Mayer and LeRoy and won his case. When asked by gossip columnist Hedda Hopper what he (Ebsen) would now do, cast as the Tin Man, Ebsen’s laconic reply was “Suffer.” His snap assessment was not too far off.

Although Mervyn LeRoy briefly toyed with the idea of having Leo (the lion featured in MGM’s corporate trademark) cast and dubbed as Oz’s Cowardly Lion, early memos suggest that comedic powerhouse Bert Lahr had already secured that part before the former concept could be given ample consideration.

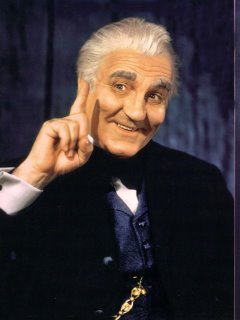

Casting choices for the part of the Wizard varied – though Arthur Freed had always wanted Frank Morgan. LeRoy had hoped for Ed Wynn. Briefly, the studio also considered W.C. Fields, who had made a stunning success apart from his usual persona as Mr. Micawber in MGM’s David Copperfield (1935). Even Wallace Beery stepped forward for consideration.

As for Glinda, the good witch of the North; casting choices veered from stage actress Beatrice Lillie to comedienne Fanny Brice. Ultimately, the former Mrs. Florence Ziegfeld – MGM contract player Billie Burke was assimilated into the role. Freed had first proposed Edna May Oliver for the Wicked Witch of the West. Contract player, Gale Sondergaard tested for the role – revamped from ugly to slinky to suit her persona. Ultimately, Freed and LeRoy chose ugliness, a move that forced Sondergaard out of the running and gave former school teacher Margaret Hamilton the role of a life time.

Initially, the writing credits on Oz had been assigned first to Irving Brecher, then Herman Mankiewicz. Dissatisfied almost immediately with Brecher, and then Mankiewicz – whose draft departed from Baum’s intimate simplicity – Mervyn LeRoy quietly employed Ogden Nash and Noel Langley on a rival script that would serve as the basis for the finished film.

Throughout these rewrites many of the superfluous and nonsensical characters that had been inserted over the course of Oz’s preliminary phase were eliminated – including subplots involving Miss Gulch’s niece, Sylvia, and Bulbo, the Wicked Witch’s incompetent son who desires to ascend the throne of the Emerald City. To smooth out the final shooting script, Freed and LeRoy assigned Florence Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf to the project. Their contributions included the creation of Professor Marvel – introducing Frank Morgan/the Wizard at the start of the film.

Meanwhile the musical portion of Oz was beginning to take shape. Freed had wanted Jerome Kern. Along the way many luminaries were considered, included Mack Gordon, Al Warren, Harry Revel, and even Freed’s former collaborator, Nacio Herb Brown, Eventually, the honors when to Harold Arlen and E. Y. Harburg.

As Oz moved from preproduction to actual shoot, the complexities that had seemed unmanageable so far were about to unravel into behind the scenes chaos.

No comments:

Post a Comment