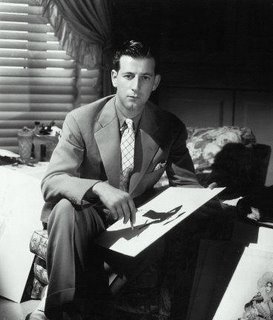

By the mid-1930s Irving Thalberg commanded the respect, prestige and authority of most moguls in Hollywood – all, it seems but those of L.B. Mayer. Although Mayer could quietly admire Thalberg’s zeal for producing some of the finest movies ever made, he was furthermore to the point merely tolerant of his executive’s talent in producing one money maker after the next for the studio. The point of contention that frequently brought the two men to the edge of blows was Thalberg’s magnificent obsession with mounting Norma Shearer's film career.

MGM produced and released 52 films per annum – an absolutely staggering output by contemporary estimates. Mayer believed in this factory-like assembly of art. Thalberg did not. Moreover, Thalberg desired to make fewer films but make them more lavish than their competitors. Ultimately, Mayer’s edict ruled; 52 movies were produced each year under his reign but many were given lavish budgets.

Midway through the decade Thalberg’s contract was renegotiated and his duties severely curtailed. Mayer used Thalberg’s health as his excuse to prune back Thalberg’s influence over all film output – a move that infuriated the young genius and arguably lead to his second attack while on holiday. Under this new agreement, the producer responsibilities were splintered between men loyal to Mayer and his son in law, David O. Selznick, and those remaining loyal to and working under Thalberg. This passive/aggressive ‘clash of the wills’ ultimately culminated in two of the studio’s most exquisitely handsome films; Romeo & Juliet, made in 1936 and starring Norma Shearer and Leslie Howard, and, Marie Antoinette, begun at the same time but delayed repeatedly until 1938).

Mayer, who shared in Thalberg’s interests for costume dramas did not care for his spending in excess and daily Mayer observed that Marie Antoinette was increasingly becoming a project of personal excesses. Undoubtedly, Marie Antoinette would be big. But would it threaten to bankrupt the studio?

For Marie Antoinette, Thalberg envisioned a four hour Technicolor epic to be road showed – a practice made popular more in the 1950s than 30s, marked by its exclusive engagement instead of an immediate general release. As a patron, one paid more for a road show. It came with the expectation of a floor show, an overture, intermission and a commemorative program. As an attendee, one was expected to dress up for the event. Hence, in deportment and accoutrements, Thalberg envisioned his film as an event akin to live theater.

A point of distinction that cannot be overlooked in Thalberg’s preproduction on Marie Antoinette was his fastidious determination to mount the film with an uncanny and firm grasp on historical settings. Together with producer Hunt Stromberg, Thalberg amassed a small library of text books on 18th century France. Most films of the 30s - either produced at MGM or elsewhere, were not as concerned with this level of accuracy. In fact, sitting in observance of films from this vintage reveals period settings very much derived from the imaginative art departments of the studios.

Take a film like Ernest Lubitsch’s The Merry Widow as example; made in 1934 by MGM and supposedly taking place within the fictional Russian province of Marshovia, and later, Paris. From Moscow to Versailles, the sets in the film are pure art deco – full of smooth lines, rounded corners, yet candle lit as they must have been in 1885, the year the story The Merry Widow supposedly takes place. This strange blend of early 20th century art noveau and deco influences combined with trappings from some misplaced historical vintage are precisely what make such rigid critiques in historical analysis impossible and frustrating for those foolish enough to pursue the undertaking. Yet, as an audience we accept the very smooth crisp polish on the floors, the ultra modern look of Jeanette MacDonald’s boudoir, in The Merry Widow as example – even though they are hopelessly and haplessly incongruous with the time in which the story should he taking place.

However, Thalberg emphatically did not want such a clash of design to exist in Marie Antoinette. His intent for the preservation of the integrity of the film’s surroundings was very much there from the start. MGM’s head of research, Nathalie Bucknail, disseminated materials assembled by Thalberg and Stromberg to all departments; 59, 277 specific reports on historical research, 1,538 books and approximately 10,615 photographs. Carter Spetner and Dave Barkell made prints from many of these pictures and replicated their art work in both the tapestries and paintings seen in the film.

MGM’s formidable art director Cedric Gibbons and his associate William Horning designed and supervised the construction of 98 full size sets – many depicting the palace of Versailles. The curiosity in this enormous undertaking, especially given to Thalberg’s attention in authenticity, was that none were an exact replica. The real entrance to Versailles for example, has no grand staircase as the one seen in the film. There is also no famed hall of mirrors, which would have been virtually impossible to photograph without seeing technicians and crew reflected back in the glass. Regardless of this artistic license, the sets proved authentic enough to earn Gibbons the respect and seal of approval from the French government.

In later years, MGM recycled portions of Marie Antoinette’s sets in many of their subsequent releases. Antoinette’s bedroom, for example, became the hotel suite for servicemen in Anchors Aweigh and a ballroom in For Me And My Gal. The throne room of Versailles appeared as the great hall in The Swan and C.K Dexterhaven’s grand foyer in High Society. Many backdrops in Ninotchka and its remake Silk Stockings derive their elegance from Marie Antoinette. Numerous props, costumes and sets reappeared throughout the cost cutting 1950s in films supposed taking place somewhere in Europe – among these, Scaramouche (1954), An American in Paris (1951) and Gigi (1959). Mayer may have been incensed over Thalberg’s initial spending, but he was well compensated in the mileage he got from that stock pile.

Edwin Willis, head of the prop department, spent three months in France purchasing a stunning assortment of antiques, furnishings, paintings, statues, scrolls, art objects, and even original letters – in the end, the largest consignment of antiques to ever clear LA Harbor customs.

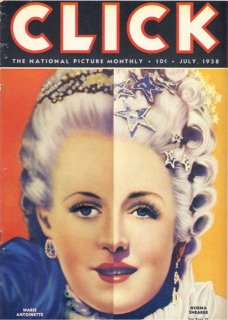

Thalberg had Gibbon’s art department import expert wood carvers – from Europe to reproduced lavish frames and moldings for palace interiors. Charles Holland, the studio’s chief draper, supervised the sewing of elaborate festoons from brocades, fringes, galloons and gimps purchased in France by Willis. Max Factor & Co. made 903 ornamental white wigs for the principal actors and another 1,200 less ornate ones for the extras.

One of the most remarkable aspects about Marie Antoinette is its score by Herbert Stothart, who was to MGM what Max Steiner had been during this same period over at Warner Brothers – a work horse. Stothart’s “in-house” musical styling effectively set the pace and tone of all MGM films from the earliest talkies until Stothart’s death in 1949. A Broadway composer who abandoned the stage for movies – because it paid better and he probably realized, like so many actors, directors, etc. that films have a greater immortality than works of the stage, Stothart’s great gift to American cinema has been his very light touch –

so much, that some say his compositions all but disappear on the screen.

so much, that some say his compositions all but disappear on the screen.For Marie Antoinette – Stothart’s forte derives from evoking the over indulgent grandeur depicted in the visuals and topping it with pomp and circumstance all his own. There’s a genuine epic quality in his orchestral handlings of the initial arrival to Versailles, the marriage processional and Marie’s various balls and parties.

The other great contribution that has yet to be acknowledged herein was that of MGM’s resident fashion guru: Gilbert Adrian, known distinctly (like Garbo) by only his last name.

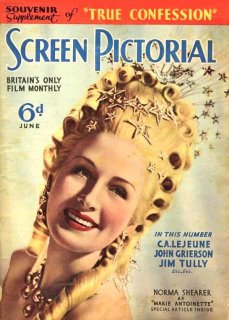

“Clothes are a woman’s first duty to herself.” Norma Shearer once declared, “It is when she is conscious of being well dressed that she can do her best work and get that superiority complex that makes for success.”

Arguably, no one wore clothes better than Shearer and equally, no one designed them with quite as much aplomb as Gilbert Adrian.

Within a few short years of his arrival to MGM in 1928, Adrian had invented the concept of the one man costume designer/couturier and was one of two men Thalberg chose to accredit with the MGM style in a 1932 Fortune magazine interview.

By 1938 Adrian was at the top of his game, setting so many trends in women’s fashion that sixty years later designers continue to borrow from his wealth of inspiration to create some of their own. The pill box hat designed for Garbo in 1932, as example, was resurrected by Halston for Jackie Kennedy in the 1960s, and in 1978, Adrian was honored with the very first retrospective of fashion at the Smithsonian.

Part of Adrian’s early success at MGM was that he realized clothing could not be theatrical with the advent of sound. As Adrian explained, “all the designers are thinking of fashion in terms of dramatic moments instead of genuine, real moments that occur in life. What I am attempting to create for the screen are ultra modern clothes that will be adaptable for the street.”

On Marie Antoinette, Adrian began his research into the period with a journey to the Royal Archives in Vienna. Effectively, he recognized that the French court during Antoinette’s reign was a gilded menagerie for gaudy fashions and he was determined to recreate this magnum opus in frivolity to its last detail on celluloid. To this end, Adrian designed literally thousands of costumes – most of them very cumbersome to maneuver in; 34 worn by Norma Shearer.

Purchasing mass quantities of silk, embroidered velvets and gold and silver lace, Adrian also hired a small army of French seamstresses to recreate the patterns worn by the real Antoinette, and employed a milliner from Russia’s Imperial Opera Company to provide guidance for hats and headdresses. Weighing in at just under 110 pounds, Shearer’s wedding dress – with its 500 yards of hand-embroidered white satin covering a steel-wired harness specifically manufactured for the occasion, added a staggering 108 pounds to her 5 foot 3 inch frame.

In fact, for each of Shearer’s 34 costumes, a special metal hanger had to be invented.

L.B. Mayer, a fairly practical and patient man, who believed that his motto of “do it big and give it class” extended only in so far as to outdo the rest of Hollywood’s output, might have put a stop to Thalberg’s extravagance at this point.

But on Sept. 14, 1936 Mother Nature remedied his concerns. Irving Thalberg died of a massive heart attack at the age of 37, leaving the unfinished trappings to Mayer’s discretion. Norma Shearer, understandably shaken by the loss, departed MGM for nearly a year during which time Mayer made several key alterations to the film that foreshortened its critical and financial success.

First to go was Thalberg’s desire to shoot the film in Technicolor. Aside from being a laboriously and cumbersome photographic process in those early years, Technicolor was incredibly expensive. A studio could expect to nearly triple its costs by shooting in color. With all the extravagance incurred by MGM thus far, Mayer was decidedly not interested in tripling anything except profits. The problem in

revising the shoot for black and white was that all the sets and costumes had been designed with Technicolor in mind. A black and white movie has its sharply contrasted image quality partly because of the lighting techniques employed on the set, but primarily because costumes and sets have been painted in colors that will photograph a certain density in black and white. As a result, most of the film as it appears today registers in tonalities of gray (or silver) rather than in the burgeoning severity of true B&W.

revising the shoot for black and white was that all the sets and costumes had been designed with Technicolor in mind. A black and white movie has its sharply contrasted image quality partly because of the lighting techniques employed on the set, but primarily because costumes and sets have been painted in colors that will photograph a certain density in black and white. As a result, most of the film as it appears today registers in tonalities of gray (or silver) rather than in the burgeoning severity of true B&W.Mayer’s next course of action was to prune the film’s running time down from four yours to just over two without a fanfare, intermission or entr’acte. But by far the most damaging decision Mayer made after Thalberg’s death was to replace director, Sidney Franklin with Woody S. Van Dyke, affectionately known around the lot as ‘One-Take Woody’. Franklin, who had been on the project from the start, had protested Mayer cutting the shooting schedule from ninety days to barely two months. But more importantly, Van Dyke was known for his frugal approach to making movies and his overall ability to commit a project to celluloid on or before the cut off date.

Norma Shearer reluctantly agreed to Van Dyke and forever afterward regretted her diplomacy on the matter. In their working methods, Shearer and Van Dyke were at opposite ends of the artistic spectrum – she, desiring time to rehearse and shoot to get it just right; he anxious to move on to the next shot after only one or two rehearsals.

Perhaps, in part to compensate for these ego-crushing frustrations on set, Norma attempted a flirtatious romance with costar Tyrone Power. Her advances were ill-timed and ill-received by Power and merely added to tensions throughout the shoot. In fact, at one point, Power teased that he would demand “stunt pay” to accompany Shearer to the premiere. Following that event, the film was screened briefly as a road show, then quickly dumped on the market as a regular feature where it did respectable business at ‘popular prices’.

The premiere had been as impressively mounted as the film itself - a lavish affair at the Carthay Circle Theater – complete with statuary and props imported from MGM’s prop department and lined with sprays of flowers. All of Hollywood turned out for the big night. Norma did indeed arrive on the arm of Tyrone Power – looking rather uncomfortable - but dapper, nevertheless. It was a long awaited premiere: three years in prep’ and two years in the making. Arguably the critics expected more from the film. A few criticized the fudging of historical fact, a point of contention that is often strangely overlooked in other period movies.

On celluloid, history is usually sufficiently cleansed of its more unpleasant aspects – particularly during Hollywood’s golden era. John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln as example, only deals with

Abraham’s ascendance from country attorney to aspiring politico, without even acknowledging the bitter end to come.

Abraham’s ascendance from country attorney to aspiring politico, without even acknowledging the bitter end to come.The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn marks a quaint snapshot of the old south that is absent of lynch mobs and carpetbaggers. Destry Rides Again and Dodge City celebrate the old west as a lusty battalion of virtuous prostitutes, playful codgers and rough-neck men wearing black. What became of the carnage that evicted Native Americans from their lands - remains a question mark unexplored by the likes of Errol Flynn, Randolph Scott or John Wayne.

So if Marie Antoinette did not entirely adhere to the true facts of history, given the climate of the 30s output in American movies – that slight is not only forgivable, but expected at some level.

In hindsight, Marie Antoinette was Norma Shearer’s second-to-last flowering as MGM’s ‘queen of the lot.’ Although she could have continued to make movies throughout the 1940s, Shearer was far more business savvy than most of her contemporaries, and certainly more of a tough cookie than recent critics have often given her credit for.

Possibly, L.B. Mayer was holding a bit of a personal grudge against Norma for having to pay out Thalberg’s shares in studio profits. Mayer’s replacement of director, Sidney Franklin with Van Dyke signaled just one way he might have felt he could exude a control over her waning career or, at the very least, make it known that the remainder of her stay at Metro would be an uncomfortable one.

But Norma too probably realized that the days of more mature

actresses reigning as stars had come to a glittering end. By the late thirties all the big name female talent that had put MGM on the map – Garbo included – had left that magic kingdom. Joan Crawford, Norma’s greatest rival, would be ousted from MGM a few years after her departure – though Crawford’s enduring legacy would continue to flourish at Warner Brothers and Columbia.

actresses reigning as stars had come to a glittering end. By the late thirties all the big name female talent that had put MGM on the map – Garbo included – had left that magic kingdom. Joan Crawford, Norma’s greatest rival, would be ousted from MGM a few years after her departure – though Crawford’s enduring legacy would continue to flourish at Warner Brothers and Columbia.She was, however, the rarity and not the reigning example.On the whole then, it can safely be said that Norma left MGM with little regrets. Producer David O. Selznick thought he might offer her the part of Scarlett O'Hara outright, but public objection killed that deal. Throughout the 40s, Norma seemed to suddenly lose her interest in film making. She continued to turn down meaty roles in films like Mrs. Miniver (1942) and retired permanently from the screen that same year to marry Sun Valley ski instructor Martin Arrouge who was twenty-years her junior. From then on - Hollywood did not take up her time.

No comments:

Post a Comment