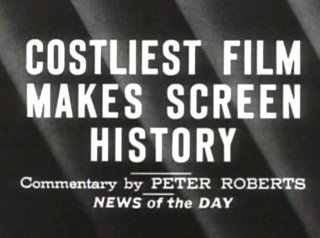

The 1925 version of Ben-Hur had been a troubled project inherited by MGM, produced by J.J Cohn and directed by Fred Niblo in Rome and at the newly amalgamated Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios in Culver City California. A colossal undertaking buffeted by costly delays and epic mistakes – most generating grand spectacle readily apparent in the final cut – Ben-Hur became a box office sensation, though at a then unheard of cost of $4

million it took several reissues for the film to break even in general release.

million it took several reissues for the film to break even in general release.MGM had spared no expense, employing over 3000 extras, investing in the costly 2-strip Technicolor process and even going so far as to construct full size Roman war ships for the sea battle sequence. Even if the film proved costly – which it did - in 1925, MGM was on the upswing – a film empire in the making. Such prestige afforded could only serve to bolster their stature for quality craftsmanship par excellence within the industry.

Fast forward to 1958 - MGM and the rest of Hollywood are in a state of quiet confused chaos. Most of the founding moguls, including L.B. Mayer have been ousted from their controlling interests. Television has cut theater attendance by nearly half. Production costs have skyrocketed in direct proportion to a downturn in much needed profits. The star system has become a thing of the past with talent contracted out on a picture by picture basis. By all accounts, the golden era is fast approaching extinction.

It was into this artistic malaise that two great happenings occurred within a few short years of one another. The first was MGM’s own gamble on Quo Vadis, director Mervyn LeRoy’s costly though lucrative 1951 religious themed spectacle shot entirely in Rome; the second was 20th Century-Fox’s debut of their newly christened widescreen process, Cinemascope with another Biblically-themed show – The Robe (1953). The critical and financial success of both these ventures, coupled with every studio’s scramble to incorporate the new anamorphic aspect ratio into their own mainstream productions by the mid-decade, had fueled producer Sam Zimbalist’s interests in remaking Ben-Hur for the postwar generation.

Zimbalist had been a cutter on the 1925 version. Like William Wyler he came to the subject reasonably well versed in what it took to create a spectacle. Of his own involvement on the project, in an interview conducted near the end of his life, Wyler playfully mused, “I thought it would be interesting to see if I could make a Cecil B. DeMille picture.”

However, in choosing Wyler to direct, Zimbalist had made a fortuitous decision that guaranteed a more intimate center to the impact of the narrative. William Wyler’s great gift to the American cinema had always been his ability to humanize a good story and make it live on the screen.

As it had done in 1925, Rome loaned its facilities to the elephantine production once again. Cinecitta Studios became home to 125 American cast and crew; the hub of activity so vast and expansive in its scope of 300 sets, that it dwarfed even the monumental pedigree of Oscar-winning art director Edward Carfagno’s efforts on Quo Vadis. Most of these sets were constructed from wood and stucco masquerading as brick, mortar and cement. The city of Jerusalem set alone covered ten square city blocks, consumed more than 40,000 cubic feet of lumber, 250 miles of metal tubing and over 1 million pounds of plaster. Although these sets were massive in scale, matte paintings were also used to enhance their grandeur in the final film.

Of all the sets constructed, the one which gave Carfagno particular satisfaction was Arius’s garden terrace – a lavish marble and granite paradise, complete with stage area and fully functional fountains. To add an air of authenticity, during the party sequence where Arius adopts Judah as his son the company invited distinguished members of the Italian aristocracy to attend in full costume. The allure of such a mammoth undertaking generated a party atmosphere on the set.

Occasionally however, Carfagno’s meticulous attention to every detail lapsed. Such as the time he placed a ripe tomato for a flourish of red on Judah’s dinner table, only to be abruptly advised by a historian that the tomato had not yet been invented in the history of cross pollination.

During the making of the 1925 Ben-Hur, the full scale sea battle had posed a genuine risk to health and safety of both cast and crew – particularly during one harrowing instance when a full size galley in the Mediterranean accidentally caught fire, sending panicked extras diving into the sea. For the 1959 version, this battle was almost entirely restaged in miniature inside a man-made tank that allowed for strict controlled conditions. For the interior sets of the great ships, 600 extras were employed as ores men. While all this manic activity in preproduction continued behind the scenes, one key element of the film seemed to be stagnated almost from the start – the development of an adequate script.

From the beginning, Wyler and Zimbalist had expressed their grave concerns to MGM; that, of the forty odd scripts submitted for consideration, even the one written by Karl Tunberg - eventually chosen as the basis for the film - was in serious need of revision. At the quiet behest of Zimbalist, friend and author Gore Vidal was hired to rehabilitate Tunberg’s draft. It was Vidal, for example, who reconceived the platonic boyhood relationship between Judah Ben-Hur and the Roman tribune, Messala as a ‘lover’s quarrel’ – so coined as to hint of a homosexual undertone responsible for their embittered divide later on. The production code of the day did not permit overt references to homosexuality – hence, Vidal’s take merely relied on long gazes between the two actors and a somewhat effeminate playful banter that quickly degenerated into Messala’s feelings of being spurned.

Near the end of the rewriting stage, blacklisted screenwriter Christopher Fry was quietly put on the payroll by Zimbalist, who together with Fry, eventually contributed to the shaping of much of the tone, texture and structure of the finished product. Fry’s great contribution was in altering the contemporary strain of dialogue to suit the period, but never in a way so that social exchanges between characters became Shakespearean or theatrical. Unfortunately for Fry, MGM balked at affording any screen credit beyond that already given to Karl Tunberg. Throughout shooting, William Wyler made repeated attempts to reinstate Fry’s credit to the film but to no avail. On the eve of the Academy Awards, Fry could perhaps breathe a smug sign of relief that, regardless of his formidable contributions to the script, Tunberg did not receive an Oscar for his efforts.

BEN-WHO? – CASTING ISSUES AND GETTING UNDERWAY

“It's eighty percent script and twenty percent you get great actors. There's nothing else to it.” – William Wyler

In retrospect, the most astonishing aspect of Ben-Hur’s preproduction is how close audiences came to never seeing Charlton Heston assume the title role. Despite Heston’s formidable handling of Moses in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956), MGM initially sought Paul Newman as their lead. Newman had by this time proven himself a formidable powerhouse at the box office with popular turns in Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), Cat on A Hot Tin Roof (1958) and The Long Hot Summer (1958).

However, prior to any of these successes, Newman had made the disastrous The Silver Chalice (1954) – a would-be epic in which Roman garb and togas seemed an ill fit for the actor. When approached with the prospect of donning similar garb for Ben-Hur, Newman flatly refused, saying, “Never again will I act a movie in a cocktail dress!”

Second tier choices for the plum role were then offered to Marlon Brando, Kirk Douglas, Burt Lancaster and Rock Hudson. In some cases, the actors simply turned down the part. In other instances, they were unavailable due to prior commitments at the time when Ben-Hur was scheduled to begin its lengthy shoot in Rome. In an unprecedented move, MGM conducted an open call – wading through a litany of svelte Italian strong men whose formidable girth and muscularity paled to their deplorable mastery of the English language. Finally, it was William Wyler who suggested Charlton Heston for the lead. Heston and Wyler had just completed The Big Country (1958) – a sprawling western in which Heston had proven himself leading man material.

It was roughly at this junction in the film’s gestation that Sam Zimbalist suffered a fatal heart attack. MGM rushed in J.J. Cohn whose easygoing nature bode well with Wyler’s congenial showmanship. The two got on famously and the production began shooting. In keeping with the times, one aspect of the script that remained a concern for Wyler even as shooting commenced was its religious connotation. Expert consultants and specialists were employed from the Vatican, as well as the Protestant and Jewish faiths to ensure the utmost sensitivity to all religions.

In reshaping Judah’s conversion to Christianity, Wyler also took considerable care in the representation of the Christ figure – shooting actor Claude Heater, who portrayed Jesus, only from the back and never with any spoken words of dialogue. To convey Christ’s genuineness, Wyler relied solely on Miklos Rozsa’s evocative compositions.

Hungarian born, Rozsa had been a child protégée who began studying composition at the Leipzig Conservatory in 1926. After settling in London England in 1935, Rosza met fellow Hungarian, Alexander Korda who commissioned him for the film; Knight Without Armor (1937). While composing for The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Rosza moved to California foregrounding his unobtrusive style that cleverly amplified and augmented the visuals of many a 1940s film noir.

On Ben-Hur, Rozsa created one of the richest, most deeply haunting and profoundly grand compositions ever recorded for film. The first fifteen minutes of score provide the perfect contrast that is Judah’s conflict throughout the story; Rosza’s introductory ‘star of Bethlehem’ motif with its ethereal choral mass, and, the bombastic and slightly garish pomp and circumstance of authoritarian Roman rule, cleverly featured beneath the main title sequence.

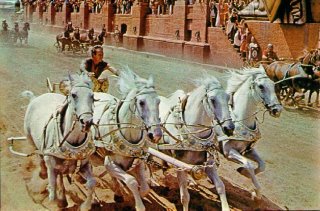

As the day neared for the shooting of the climactic chariot race sequence, second unit director Yakima Canutt and Charlton Heston rehearsed a team of horses around the massive Circus Maximus that Carfagno had built on the backlots at Cinecitta. While both Heston and Stephen Boyd (Messala) did a fair amount of the driving during the execution of this sequence, the more ambitious stunts were left in the capable hands of Canutt’s son; stuntman Joe Canutt. Despite endless planning and rehearsals, two accidents occurred during this shoot.

The first involvement Joe, whose failure to slow his team of horses around a hair pin turn literally tossed the stunt man into the air for a few harrowing moments. The second casualty during the shoot was one of MGM’s massive Camera 65 widescreen cameras. Worth a whopping $100,000 and stationed at the edge of another hairpin turn, the camera was trampled under the hooves of galloping horses when several charioteers lost control of their steeds.

FARED-WELL and CODA

Upon its release, the New York Times simply glowed, describing Ben-Hur as “by far the most stirring of the Bible-fiction epics!” Perhaps no greater accolade could have been afforded William Wyler – although the Academy Award for Best Director probably came close. To be certain, Wyler’s Roman saga is unlike any of the others to emerge from that heady obsession that Hollywood once had with ancient civilizations. From end to end, the film is teaming with life.

Wyler once commented that “story dictates technique”- but this is an oversimplification of ‘the Wyler touch.’

Hence, when one considers his films in totem in recollection today, and Ben-Hur in particular, they are far more tales of intimacy than scale. Ben-Hur is the perfect example; it is a poignant familial saga that functions very much like a quiet parlor drama. The size of the production is never once allowed to overshadow or eclipse any ‘minor’ detail. “I like to do stories that have a personal appeal,” Wyler once commented, but then again, that goes without saying.

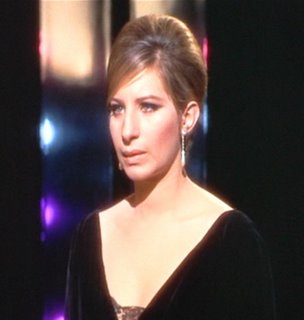

In the last decade of his career, William Wyler showed little signs of slowing down. He remade ‘These Three’ under its original title as the more honest and engrossing, The Children's Hour (1961). He explored bigotry in The Collector (1965), returned to the romantic comedy with the modestly successful, How To Steal A Million (1966) and had his final mega hit with Barbara Streisand’s debut, Funny Girl (1968).

His last film, The Liberation of L.B. Jones (1970), was a minor failure, and although he dreamed of making more movies, ill health precluded William Wyler from ever assuming the directorial reigns again. Content to spend the rest of his life vacationing with his family, William Wyler died on July 27, 1981 at his home in Beverly Hills. He is arguably best remembered today for Ben-Hur – the intimate epic: but it is one of many immortal classics in his canon of truly inspired accomplishments.

@Nick Zegarac 2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment