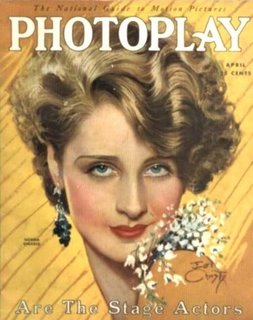

It was the costly film ever attempted by any studio; a sumptuous feast for the eyes, destined for the annals of film immortality. In every detail, it should have been the most magnificent spectacle ever created; and, although arguably it fell short of these superlatives, Marie Antoinette proved to be just as turbulent an undertaking as those last fateful days inside the French court of Versailles. As an artifact of the 1930s, Marie Antoinette figures prominently in the legacy of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer; the studio with “more stars than there are in heaven,” dedicating this magnum opus to its greatest star of that period and ‘queen of the lot’ – the lovely and talented Norma Shearer.

Any intelligent critique of Marie Antoinette must begin with the back story regarding MGM’s hierarchy. For it is a fairly secure assumption that the project would never have been undertaken without the persistence of Vice President, Irving G. Thalberg. At a diminutive five feet, eleven inches

in height – Thalberg was not terribly prepossessing in stature. He was, also very young.

in height – Thalberg was not terribly prepossessing in stature. He was, also very young.Indeed, the first time Norma Shearer met Thalberg she thought she was speaking to an office boy. After showing her the way to his office, Thalberg quietly too his seat behind the imposing desk, explaining, “I am Irving Thalberg.”

He was born Irving Grant Thalberg in Brooklyn New York on May 30 1899, of German extraction and cursed with a fragile heart that would later lead to other ailments. He was, as actress Luis Rainer once described him, “a fine, intelligent, marvelous, extraordinary” individual with an insatiable appetite for great literature and an almost manic thirst for knowledge.

There was something of the fatalist in Thalberg too. He was convinced he would not live to see 30 – a prophecy that was not far of its projected mark. There was also something of the skeptic in him. For example, immediately following the Warner Brothers release of The Jazz Singer (the first talking picture in 1929) – Thalberg issued a statement to the trade papers saying that “the talking picture has its place…but I do not believe it will ever replace

silent movies any more than I believe Technicolor will replace B&W”.

silent movies any more than I believe Technicolor will replace B&W”. In hindsight, Thalberg’s statement seems rash and dismissive and in retrospect, decidedly misguided on both accounts.

However, there was not much else during his all too brief tenure that the ‘boy genius’ got wrong. Ditching college for a chance at a high level executive position under Carl Laemmle then the president of Universal Studios, Thalberg rose through the ranks quickly. Unfortunately, Laemmle had a son, Carl Jr. and soon Thalberg realized that the autonomy and control he craved would never be his at Universal.

So, in 1924 Thalberg signed with Louis B. Mayer, and the fledgling studio MGM. The conglomerate of Metro Pictures, L.B. Mayer Productions and Samuel Goldwyn Pictures had recently incurred great difficulties on two elephantine projects; Eric Von Stroheim’s Greed and the original silent version of Ben-Hur.

Driven by work, Thalberg quickly gained control into every facet of the motion picture business. Apart from exuding an almost invisible manipulation of the studio’s daily operations, Thalberg also possessed an uncanny knack for choosing stories that made money; the net result - MGM was the only studio to show a profit during the Great Depression.

However, if Thalberg was the ultimate puppet master of his domain, he was also gracious and insistent about remaining conspicuous throughout the creative process. He once said, “credit you give yourself isn’t worth a damn” and too this end, no film made during his tenure ever carried his producer credit. (The exceptions: The Good Earth (1938) and Goodbye Mr. Chips (1939) bear a fond dedication to Thalberg, affixed to the main titles after his death). Though Thalberg’s personal participation in individual projects was arguably minimal; the one exception was his fastidious personalization in the films involving his wife, Norma Shearer.

Shearer was born Edith Norma Shearer in Montreal Canada, on August 10, 1902. She won a beauty contest at age fourteen, but reportedly was rejected in the follies by Broadway impresario, Florenz Ziegfeld Jr in 1920, for having a lazy eye and somewhat ‘fattish’ legs. Undaunted by this early rejection and persistent to a fault, Norma’s extra work in movies brought her to the attention of Thalberg in 1923. From their aforementioned auspicious initial meeting, Norma made her romantic intentions well known around the backlot - “I’m out to get him.” In 1927, she did just that in a private (by Hollywood standards, anyway) cerimony.

NORMA & IRVING …a love story

In many respects, Norma and Irving were ideally suited, but particularly in the business of making movies. Both were headstrong. Yet, each complimented the other in private life. Thalberg truly worshiped Norma as a star that he could mold.

She acquiesced – at least partly, to his request to retire from the movies after marriage – by playing the role of the doting wife and mother in between films – laying out his clothes before they went out in the evening. By 1929, Thalberg’s commitment to his wife’s career had transformed Shearer respectable popularity into a star of the first magnitude. Her one and only Oscar win for The Divorcee (1930) cemented L.B. Mayer’s belief in her bankable as well. He had initially had his doubts.

But any and all speculation regarding Shearer’s staying power – and her tenable position as ‘queen of the lot’ was eclipsed by a review in the New York Times, immortalized her acting prowess with “There is no other personality quite like Norma Shearer. When you check the stars and the leading women of all the other studios today this fact becomes all the more apparent. She is always sparkling, gay, always clever, always a trifle naughty, stopping just at the right second, advocating the right thing to do for every woman…to live, laugh, love as her heart dictates, quite the sort who makes her own conventions, the type who can do the very thing that in other women would be cheap or common.”

FACT OR FICTION

– the ‘REEL’ to ‘REAL’ of MARIE ANTOINETTE

If the moniker ‘queen of the lot’ had effectively stuck to Norma’s reputation by this time, then Thalberg’s extravagant obsessions in mounting his lavish production rivaled those artistic precepts born from the monarch in history.

Queen Marie Antoinette was born on All Souls' Day, November 2nd 1755, in Vienna and baptized under the names Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna. She was the youngest daughter of Maria Theresa and Emperor Franz Stephan. As an Archduchess she grew into a life of sublime privilege, her marriage to Louis Auguste, the dauphin of France, more an affair of state than an affair of the heart.

Ironically, her schooling was limited, though she dabbled in music most proficiently and even played a duet with child protégée Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in the Palace of Schönbrunn. On April 21, 1770 Maria left Vienna for France, never to return. En route to her new home she was the guest of Cardinal Louis de Rohan, the man who would later crucify her reputation with the French people over the so-called “Diamond Necklace Affair.”

A court of intrigues and temptations, Versailles captivated Maria’s fascination with superficiality. Without formal education or, for that matter, self control, Maria became the brunt of insipid gossip. Her husband, the Dauphin Louis-Auguste, was a backward young man with a bit of cruel streak. Whether from sexual frigidity or just an innate detestation from being forced to marry anyone, the future king of France did not consummate his marriage to Antoinette for seven years.

In the film, Marie Antoinette, there remains a marvelous scene of pure fiction in which Madame Du Barry, King Louis 15th’s mistress, sends the king’s son and Maria an empty cradle as an obvious snub on their second anniversary. The inscription reads: “as it is obvious this cart you are unable to fill, go back to your schnitzel and kraut, leave the duties to some baggage that will.” During the first half of the film, Du Barry is very much conceived as the story’s villain. Gifted character actress Gladys George puts a rather spiteful spin on Du Barry that is driven by greed and generally out to conquer the monarchy.

In fact, Madame Comtesse Jeanne Du Barry was a courtesan of illegitimate birth and the mistress of Jean Du Barry before gaining Louis 15th’s favor in 1768. A social climber, who lacked in both the venom and ambition of her predecessor, Mme de Pompadour, Du Barry married her lover's brother, Guillaume, comte Du Barry in 1769. Her influence over the king was minimal, though she did become his lover. In the film, Du Barry drives a wedge between father and son.

She is portrayed as a conniving manipulative shrew of formidable power within the French court. In reality, she was arrested by the Revolutionary Tribunal on charges of treason and guillotined in 1793.

In 1774, King Louis 15th died. Dauphin Louis Auguste ascended the throne and Maria became Queen of France. Her mother, the Empress petitioned prudence and decorum from her daughter in a litany of correspondence, but Marie would have none of it. In fact, her self indulgences escalated even though her reputation with the people of France had already by this time degenerated into that of a wanton foreigner.

It behooves pointing out that in the filmic Antoinette, Maria’s carefree naughtiness is made as rebuttal for the rejection she’s received from her husband. By the time Louis 15th expires, the filmic Marie has resorted to having one intimate love affair (presumably unbeknownst to anyone in or out of the French court) with Count Axel Ferson. Hence, by the time Louis-Auguste becomes king in the film Marie has mended her wicked ways.

The intrinsic logic behind MGM’s revisionist history is acceptable, if not by purist standards at least by Hollywood’s. Norma Shearer’s early career had leant itself to playing déclassé women bordering on femme fatales. But in 1934 the Catholic League of Decency and the Hayes Office for self regulation in motion picture entertainment had made it clear that “the tawdry, the cheap and the vulgar” would no longer be acceptable parts of the filmic cannon. All women of late 30s vintage would either have to become ladies or die trying. Hence, by the time Marie Antoinette premiered, the expectation that the queen would be a benevolent ruler was a given.

Norma’s interpretation of Antoinette is very Christ-like. For example, the quotation most readily recanted by the real Antoinette is her blunt and thoroughly obtuse rebuttal with regards to what should be done about the starving populace of France – “Let them eat cake!” However, this line is never uttered in the film solidify the fiction that Antoinette was not a wanton, but rather a martyr whose greatest sin was to be at the wrong place at the wrong time.

This saintly critique is ascribed to the1785 notorious “Diamond Necklace Affair.” History explains that the Cardinal de Rohan was duped by a trickster named Jeanne de la Motte into purchasing a lavish necklace in the queen’s name. Rohan, who had fallen from the queen’s good graces, believed that la Motte’s commission meant a return to favor with her majesty. Instead, la Motte smuggled the jewels to England. When the expected payment for the necklace failed to materialize, the jeweler took his claim to the crown.

Appalled by the deception, Marie ordered that Cardinal de Rohan to stand trial – a fateful error in judgment. For although Jeanne de la Motte was convicted of the crime - the cardinal was acquitted by the Parliament of Paris – a miscarriage of justice openly celebrated as a victory over “that Austrian”; the general consensus, that Marie had been involved at some level in the conspiracy and had used Rohan as her scapegoat.

After Marie’s earlier extravagances had bankrupted the royal treasury the Estates-General emphatically refused to vote on an increase in taxes. Instead they swore an oath to give France a constitution. The seeds of revolution had been planted. Forced into abdication, Louis 16th attempted an appeasement by agreeing to a constitutional monarchy. But the Revolution attacked the Catholic Church; a move akin to turning against the king. Fearing for their lives, on June 20th, 1791, the royals fled Paris; apprehended en route and incarcerated in the Temple Prison. On January 21st, 1793, Louis was publicly beheaded.

In the film, these final elements of court intrigue and daring escape are interwoven into the fictional romantic hero of Count Ferson, played by 20th Century-Fox heartthrob, Tyrone Power, and the villainous Duke Phillipe d'Orleans, played by character actor, Joseph Schildkraut. Ferson is arguably the film’s most flawed attempt at fashioning romance, but Phillipe bears further discussion in historical fact.

In life, Louis Philippe Joseph duc d’Orlean was born to prominence on April 13, 1747 and called Philippe Égalité. He was a member of a cadet branch for the House of Bourbon, the dynasty then ruling France and actively supported the revolution. Schildkraut’s Philippe becomes the demigod that replaces Gladys George’s Du Barry as the heavy in the film. After the affair of the necklace Phillipe is offered a sizable portion of the king’s estate in return for his influence in helping to quell the revolutionary flames; regency never granted in historical fact. Perceived as something of a patriot, Philippe was nonetheless guillotined.

On October 14th 1793 Marie Antoinette was formally charged with high treason and illicit sexual practices. This

latter charge was tacked on to dissolve any remaining sympathies that women might have with Marie as a mother. There are few who would disagree that the last days of France’s monarchy were tumultuous and chaotic. Yet, in the film, this chaos is barely glimpsed, but instead left to Norma Shearer’s prowess as an actress to convey, almost entirely without words as she is being lead to the guillotine; her face bearing such deep emotional scars – such a strange and virulent concoction of sheer terror and complete surrender – that its cumulative effect is one of accepted lost innocence caught in a maelstrom of brutality.

latter charge was tacked on to dissolve any remaining sympathies that women might have with Marie as a mother. There are few who would disagree that the last days of France’s monarchy were tumultuous and chaotic. Yet, in the film, this chaos is barely glimpsed, but instead left to Norma Shearer’s prowess as an actress to convey, almost entirely without words as she is being lead to the guillotine; her face bearing such deep emotional scars – such a strange and virulent concoction of sheer terror and complete surrender – that its cumulative effect is one of accepted lost innocence caught in a maelstrom of brutality.On Oct. 16th, 1793, the day of her execution, the real Marie Antoinette wrote a letter of farewell to her sister-in-law, Madame Elisabeth, who was still in the Temple prison. The loose translation is “I have just been condemned, not to a shameful death, which can only apply to felons, but rather to finding your brother again. I seek forgiveness from all whom I know, for every harm I may have unwittingly caused. Adieu, good, gentle sister......I embrace you with all my heart as well as the poor, dear children...."

No comments:

Post a Comment