picture this is in 20 years.”

picture this is in 20 years.”– George Stevens after winning his Best Director Oscar for A Place in the Sun (1951).

Among his many formidable attributes, director George Stevens was a humanist; a “ten plus” so described by actress Jane Withers, and above all else, a compassionate storyteller. For although he could frequently adopt the immoveable persona of a block of granite – primarily about elements in the film-making process that he felt most passionate – in life, Stevens was a witty, literate and comical presence; a director who could be tough on crew, but emphatically appreciated and admired the craftsmanship of actors.

At the core of his meticulous planning was a solid commitment to the structure and visual design of a film. He was often prone to improvisation on the set and emphatically resisted the urge to pre-conceive anything beyond the general framework of any film which he had given considerable thought to. Yet George Stevens' editorial comment on life was always bigger and nobler than life itself, placing human aspirations, dilemmas and the courage to solve them at the forefront of his narrative design.

“A motion picture should be respected as being more than a tool for selling soap, toothpaste, deodorant, used cars, beer and the whole gamut of products advertised on television.”

George Stevens once confided, that given the option of having to sacrifice his authority over one of the three primary principles in film making (1): preproduction, (2): directing, (3): postproduction that he would give up the directing every time. “If the script is good, the actors are good I can get in the editing room and make it work.” Despite such a claim, it seems unlikely that Stevens would have ever contemplated surrendering any part of the creative process to lesser hands – for he was a man unfamiliar with compromise, particularly in the realms of

personal integrity.

personal integrity.He was born George Cooper Stevens in Oakland California on December 18, 1904 and raised in San Francisco. His modest hobby of photography translated into a small business and, at age 17, a chance to be an assistant camera man at Hal Roach Studios on “Rex: The King of Wild Horses” an early serialized western adventure yarn. “There were no unions,” Stevens later explained, “so it was possible to become an assistant cameraman if you happened to find out just when they were starting a picture.”

Honing his craft as a cinematographer over the next few years, Stevens

photographed most of the early Laurel and Hardy comedies, turning some of his attention to ‘gag’ (comedy) writing. Colleague and friend, Joseph L. Mankiwiecz commented that “He was remarkably funny, but with a sarcasm that I wouldn’t have liked to have been on the other end of.”

photographed most of the early Laurel and Hardy comedies, turning some of his attention to ‘gag’ (comedy) writing. Colleague and friend, Joseph L. Mankiwiecz commented that “He was remarkably funny, but with a sarcasm that I wouldn’t have liked to have been on the other end of.”Of his own fallibility, Stevens once said, “I see myself capable of arrogance and brutality...That's a fierce thing, to discover within yourself that which you despise the most in others.” Yet, those cast and crew who knew him best were perhaps unaware of either that ‘arrogance’ or ‘brutality’. Instead, what they experienced was a man’s unerring belief in his own talents and his great passion for living.

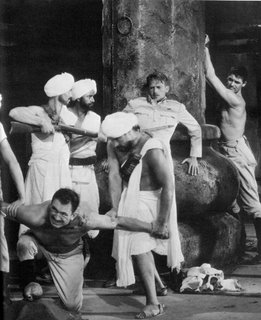

At the age of 23, George Stevens began his directorial career at RKO with Alice Adams (1935) a poignantly introspective melodrama about a wallflower desperate to be accepted in café society. His tenure progressed along side his tastes in genres running the gamut from dizzy screwball comedies (Vivacious Lady 1938), to light-hearted musicals (Swing Time 1936) and the enthralling action/adventure, Gunga Din 1939.

Despite these critical and financial successes, Stevens was under constant scrutiny from RKO to pare down his dedication to shooting a lot of film. What is perhaps most remarkable about Steven’s place within the studio system is that he was one of a few individuals who stood firm against artistic encroachment without suffering any sort of repercussions. Lacking any sense of economy and, with the ingrained perception that the artistic achievement inherent in any film is primarily the domain of its director, Stevens generally ignored such ‘suggestions’ from his bosses, especially since they did not bode well with his own frame of reference.

Departing RKO, Steven’s freelanced at MGM with the first memorable teaming of Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn in Woman of the Year (1942). A move to Columbia Pictures did little to alter his solid chemistry at the box office. He directed back to back comedy classics; The More The Merrier (1942) and the Oscar nominated, The Talk of the Town (1943). But his greatest passion of the period was his blind faith in the newly created Director’s Guild.

His light-hearted approach to film making was forever altered after screening Triumph of the Will – Leni Riefenstahl’s potent Nazi propaganda film. Reportedly, Stevens enlisted in the Armed Forces the very next day, receiving a commission from General Eisenhower as a Major for a film unit affectionately nicknamed ‘The Stevens Irregulars.’ Documenting D-Day at Normandy, the Battle of the Bulge and the crossing of the Rein, it was the liberation of Nazi prisoners from Dakow that most affected his later film work. From thereon, his projects increasingly took on the flavoring of an impassive and pervasive sadness.

George Stevens return to civilian life also led to a change of venue. No long content to be at the whim of impatient studio executives whom he felt neither understood nor accepted his meticulous and methodical pacing on the set, or his extravagance in coverage of each particular scene, Stevens launched the independent production company Liberty Films together with directors William Wyler and Frank Capra. Beginning with 1948s I Remember Mama, the tone of Stevens’ films became darker and more serious. Yet, if the comedic panache that exemplified his earlier works had been jettisoned, Stevens retained his compassionate embrace of human ideals that had always made his stories so compelling.

He topped out his Hollywood tenure in the 1950s with four quintessentially dramatic and emblematic films of the period that have since acquired a longevity and poignancy apart from their vintage; the intimately brooding and tragic, A Place in the Sun (1951); the revisionist take on manly heroism in the old west in Shane (1953); the resplendent and sprawling redux on culture and clash of sensibilities in Giant (1956); and the profoundly personal approach to one of WWII’s great personal losses in The Diary of Anne Frank (1959).

Stevens would make only two more films before his death from a heart attack on March 8 1975; The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) and The Only Game in Town (1970). Although in retrospect neither seems to entirely fit the bill of his enduring legac

y – each is blessed with Stevens’ uncompromising compassion for the human spirit. It is that quality primarily that has made so many of Stevens’ contributions to the tapestry of American film art an impressive and ever renewing wellspring of inspiration for audiences and film makers alike.

y – each is blessed with Stevens’ uncompromising compassion for the human spirit. It is that quality primarily that has made so many of Stevens’ contributions to the tapestry of American film art an impressive and ever renewing wellspring of inspiration for audiences and film makers alike.“If you could put a man into three words,” director and friend Rouben Mamoulian reasoned, “Honor, talent, courtesy. Those three were the outstanding ingredients of George. He was a stylist. His films are biographical. You see it from a more poetic point of view. It’s life elevated a step up…making the invisible visible.”

@ Nick Zegarac 2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment