Orson Welles

by Nick Zegarac

“I’ve wasted the greater part of my life looking for money and trying to get money; trying to make my work on this terribly expensive bait box which is a movie. And I’ve spent too much energy on things that have nothing to do with making a movie. It’s about 2% movie making and 98% hustling. It’s no way to spend a life.”

– Orson Welles

Arguably, the career of Orson Welles is best summated as maniacal impetus shattered with willful precision and self-destructiveness. No other aspiring filmmaker arriving at the golden foothills of Hollywood’s paradise circa 1940 was so widely embraced or publicly revered. Celebrated as ‘lightening in a bottle,’ Welles’ meteoric rise to prominence was perhaps doomed to an equally cataclysmic end.At least, such is the discretion of reflections bestowed on Welles’ legacy by film scholars in hindsight.

“The word genius was whispered into my ear, the first thing I ever heard, while I was still mewling in my crib,” Welles would later explain, “So it never occurred to me that I wasn’t until middle age.”

As diverse as Welles talents were (actor, director, producer, star) his was a legacy systematically and deliberately dismantled behind the scenes almost from the moment he crossed that threshold. Within a few short years of his arrival in Hollywood, Welles would be discredited as a fake whose ego was much larger than his talent. To what extent Welles contributed his own downfall remains a topic open for discussion. Although there can be little doubt about his imminent foresight and vision for uniqueness and quality on film, when it came to networking the Hollywood community to his advantage, Welles was perhaps ill prepared to deal with the order of moguls lurking beneath Tinsel Town’s loose superficialities. He was, after all that has been written and said of the man, a person used to getting things done his own way.

He was born to affluence as George Orson Welles in Kenosha, Wisconsin on May 6, 1915. His father Richard Head Welles was a successful inventor; his mother a skilled concert pianist. Groomed as a child protégée on par with the geniuses of Mozart, Einstein and Proust, Welles’ youth became the repository of rumors that quickly filtered into truths within a child’s fertile imagination. However, at the age of nine Orson lost his most ardent admirer when his mother died. For the next few years he became a world traveler – a cook’s tour that ended at the age of 15 when his father died of acute alcoholism.

Becoming the young charge of prominent Chicago physician Dr. Maurice Bernstein in 1931, the rest of Welles’ youth remains something of a sporadic mystery in events. He graduated from The Todd School in Woodstock, Illinois, but little is known about his boyhood friends or burgeoning relationships with young women. His early life of privilege was rumored to include an education on the art of magic from no less an authority than Harry Houdini and an ambitious masterwork that Welles penned on the history of live theater. Yet, formal education seemed to bore him. “They teach anything in universities these days,” Welles reflected, “You can major in mud pies.”

Welles rejected various offers to attend college, choosing instead a trip to Ireland. If his mind was intellectually fastidious, his heart and spirit could not be tamed to any one pursuit. After several failed attempts at carving out an acting career on either the London or New York stage, Welles traveled to Morocco - then Spain where he briefly toyed with aspirations as a bull fighter.

On the recommendation of playwrights Thornton Wilder and Alexander Woollcott, Katherine Cornell's prestigious repertory road company agreed to cast Welles in a minor role for his New York debut as Tybalt in 1934. But Welles’ greatest personal triumph of this early period was his involvement with the Federal Theater Project; a depression era work program that was part of the WPA. Assuming the reigns of an all-black production of Shakespeare’s Macbeth at the Lafayette Theater in Harlem, Welles inadvertently fell under repeated criticism from William Randolph Hearst’s media network for his gauche attempts to impose high brow entertainment on the low brow masses.

“I want to give the audience a hint of a scene,” Welles explained, “Give them too much and they won’t contribute anything themselves. Give them just a suggestion and you get them working with you. That’s what gives the theater meaning: when it becomes a social act.”

Despite open and relentless criticism – and a physical assault on his person one night after rehearsals – Welles’ off Broadway debut of the ‘voodoo’ Macbeth achieved a level of notoriety and critical praise that shocked even his most ardent detractors.

Delving head first into his new found professional success and popularity, Welles was often a tyrannical presence in his pursuit of perfectionism. “I don’t say we all ought to misbehave,” Welles would later recollect, “But we ought to look as though we could.”

His personal life was quite another matter. A fledgling first marriage to Virginia Nicholson was already crumbing. When Welles was not rehearsing a new play or appearing on the radio (as the voice of The Shadow and countless other characters for CBS and NBC), or realizing his first dream; the establishment of his own repertory company ‘The Mercury Players’ (in 1937), the young zeitgeist drank, ate and womanized to excess.

By most accounts Welles was untamed – with a relentless drive and desire to advance his stature, whatever the emotional, physical or psychological costs. However, at the crux of his debaucheries remained a curious anomaly; that despite Welles’ zest for engaging in conflict with whatever force of nature dared get in his way, he always managed to escape the maelstrom unscathed and, in fact, more celebrated than ever.

“Nobody who takes on anything big and tough can afford to be modest.”

– Orson Welles

In 1938, the second monumental hiccup in his career catapulted Welles to instant stardom in a town he had yet to set foot inside. Debuting his version of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds – ingeniously disguised as legitimate news on his nightly ‘The Mercury Theatre On The Air’ radio program, Welles managed to cajole, then terrorize his listening audience under the aegis that the fictionalized events being enacted were actually taking place. Despite the incredulous testimony and retraction that Welles was forced to offer to the press in an interview immediately following his broadcast, he had known fifteen minutes into it that his words had generated minor mayhem across the country – and he had relished every minute of that affixed giddy excitement. “Everybody else who tried that was thrown in jail,” Orson later mused, “I got a contract.”

At the age of 25, Welles was offered a contract with unprecedented amenities at RKO Studios, including complete autonomy and free reign to choose any project his heart desired. However, like most deals that seem too good to be true at the start, Welles’ signing with RKO proved to be just that. Dubbed the “would-be genius” by gossip columnist (and Hearst stooge) Louella Parsons, Welles initial proposal for an avant guarde retelling of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (as seen entirely from the protagonist’s point of view) was met with indifference first, then outright rejection from studio heads. Welles next suggested Smiler With A Knife – a British thriller loosely based on Jack the Ripper. Once again, RKO balked at the idea.

Seemingly bored with his stalemate, Welles indulged himself in the superficial pursuits of celebrity. He began courting Hollywood star, Dolores Del Rio during this hiatus. Their romance was short lived. “We’re born alone,” Welles would later reflect, “We live alone. We die alone. Only through our love and friendship can we create the illusion for the moment that we’re not alone.”

Far more lucrative (and ultimately destructive) was Welles association with screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz whom he had met at a party. The burly gambler/drinker complimented Welles’ own penchant for excess. But Mankiewicz’s thorough disgust for Hollywood bureaucracy in general increasingly exacerbated Welles own growing distemper and dissatisfaction with RKO.

Together, Welles and Mankiewicz generated the script that would ultimately become Citizen Kane (1941). Infusing their fiction with a thin veneer of truth derived from the life of William Randolph Hearst, Welles and Mankiewicz concocted a scathing portrait of a man crushed beneath the weight of his own appetites. Ensconced in Xanadu, the film’s fictional version of Hearst’s own pleasure palace San Simeon, Kane is a reclusive destructive and shattered individual – a man so lost in his own state of embittered loneliness that he possesses no sense of reality beyond his own finger tips.

That many of the film’s sequences bore little resemblance to Heart’s actual life circumstances was a moot point. There was enough of Hearst in Kane to infuriate the baron of yellow-journalism to distraction. Mankiewicz’s motives for giving a copy of Kane’s script to actor Charles Lederer, the nephew of Marion Davies, the woman who shared Hearst’s life, remains unclear. There can be little to suggest that he could not have foreseen the impending boycott of the film that was to follow.

Particularly in Mankiewicz’s reconstituted portrait of Davies, Citizen Kane created a heartless and dim-witted flaxen alcoholic as her screen substitute – wholly incendiary and far removed from the real life woman. Mankiewicz even found room in the script to insert a reference to ‘Rosebud;’ the affectionate nickname Hearst is rumored to have labeled Davies’ private parts. In the film, Rosebud is a sleigh glimpsed at the start of the story. It represents the singular object Kane values more than all his worldly riches. The sleigh resurfaces at the end of the film, as auctioneers rummage through Xanadu’s treasures they wantonly toss it into an incinerator – presumably, because it seems to have no monetary value.

RKO green lit Citizen Kane for approximately $687,000 – a grand sum for its time. Together with cinematographer, Gregg Tolland, Welles set about envisioning a most ambitious departure in style and design. Even today, the film’s deep focus cinematography and stark use of lighting, coupled with minimalist sets, evoke a quiet spirit and mood of stark isolation that is unlike anything seen on the screen. Welles ensured complete secrecy by operating on a closed set. But when Louella Parson’s rival gossip queen, Hedda Hopper received the privilege of pre-screening Kane (and declaring it a masterwork) Parson’s demanded like treatment. Her response hardly echoed that of her competitor. Instead, Parson’s frantically wired Hearst that he must stop Kane’s general release at any and all costs.

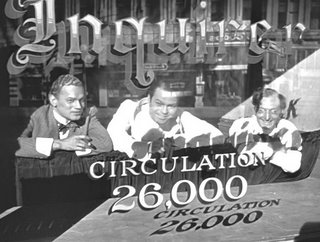

Hearst’s publishing empire then spanned and dominated circulation across the United States. He had already made the Hollywood moguls cower with the prospect of making or breaking their careers on a whim, using whatever means of intimidation suited him best. A man of finite determination and iron will Hearst’s reputation for getting what he wanted had been well established by the time Parson’s edict became his law against Citizen Kane. Upon rallying the elite in the film industry to his cause, Hearst demanded that RKO destroy every known print of Citizen Kane. MGM’s L.B. Mayer reportedly offered the studio $800,000 for the original camera negative.

Aware of the fervor and gaining momentum in controversy, RKO studio executives held an emergency meeting in New York where Welles vehemently defended his project. Publicly, RKO concurred with Welles and sent the film into general release. Privately, however, the FBI opened a file on Welles’ at the behest of Hearst. His newspapers daily condemned the genius, first as a suspected communist, then as a possible homosexual and sodomite; thoroughly unfounded allegations that nevertheless made RKO wary by association.

Even though Kane was released to acclaim from the New York critics, its circulation was limited thanks to Hearst’s pursuant litany of hollow but threatening legal actions against any theater brave enough to show the film. Nominated for nine Oscars, the film was denied virtually all except one: the win for Best screenplay. The Academy’s snub, coupled with RKO’s negative losses of $150,000 confirmed Citizen Kane as a commercial failure. The studio quietly withdrew it from circulation. It remained buried and forgotten for nearly a decade.

Disheartened by the film’s financial debacle and the way RKO had unceremoniously yanked Kane from circulation without a fight, but still owing the studio another project, Welles' dove headstrong into The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) – a $1 million sordid tale of incestuous familial relations at the turn of the century. An adaptation of Booth Tarkington’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, the film was widely perceived as a ‘safe’ follow-up to recoup losses incurred by Kane.

The story concerns a handsome though somewhat unpredictable Eugene Morgan (Joseph Cotten) who desires marriage to Isabel Amberson (Dolores Costello); a daughter born to affluence who marries stuffy but safe millionaire Wilbur Minafer (Don Dillaway) instead. Their only child, George (Tim Holt), develops into a compulsively obsessive manipulator. Upon Wilbur’s death, the mature and now financially successful, Eugene returns to ask for Isabel’s hand once again. Resenting their burgeoning romance, George and his Aunt Fanny (Agnes Moorehead) thwart the relationship before tragedy befalls the family clan. The novel had been a haunting sprawling saga peppered in private secrets and public debauchery.

However, during postproduction, and at the behest of Nelson Rockefeller, Welles left the United States to begin shooting a documentary for the United States war effort entitled ‘It’s All True’ with the understanding that all editorial decisions regarding The Magnificent Ambersons would be made with his complicity via telegram. Instead, RKO relieved Welles’ staff of the project and promptly installed Robert Wise, who excised over fifty minutes of footage. The final insult was a tack-on upbeat ending – reshot after Welles departure from the project that Welles categorically abhorred and admonished in a litany of memos. The film, incoherent with its re-shot and re-edited continuity was released to the general public without much fanfare. It quietly came and went, failing to recoup its production costs.

As for ‘It’s All True;’ RKO deemed Welles’ rough assembly of silent footage as worthless and scrapped the project. This footage remained undiscovered in their vaults for nearly forty years, mislabeled as ‘stock.’ However, not long before Welles’ death 314 cans of film, virtually all of the surviving footage was rediscovered and released in 1991 under the same title. The footage provides tempting insight into one of many Welles’ butchered masterpieces that might have been.

No comments:

Post a Comment