by Nick Zegarac

“When you are down and out something always turns up…and it is usually the noses of your friends.”

– Orson Welles

It is said of time, that it heals all wounds - perhaps. Certainly in the case of critical respect over Citizen Kane and, to a lesser extent, The Magnificent Ambersons, time has revised the wealth of subtext infused in both projects and exercised fully by Orson Welles’ creative zeal. But for their time, neither film seemed worthy of his preceding reputation as a genius. With back to back flops to his detriment, RKO – no longer interested in Welles’ services as a film maker - unceremoniously let it be known throughout the industry that they considered their ex ‘boy wonder’ a terrible risk.

The snub might have ended any other career, but not Welles’. Although he did suffer under scrutiny from the studio system as an independent film maker from the tarnishing of his reputation, as an actor, Welles was very much in demand.

20th Century-Fox exploited Welles as the embittered Rochester in their production of Jane Eyre (1942) which Welles also directed, though he received no public credit for his efforts behind the camera. Welles also appeared to reasonably good effect, alongside his Mercury Theater troupe in a thriller he produced, Journey Into Fear (1943). He co-wrote the film with Joseph Cotten. Although Welles would emphatically deny that he co-directed the film, certain sequences bear his ambitious hallmark for expressionism. A modest hit, Welles eventually dismissed Journey Into Fear as merely a passable venture.

If Welles professional career was mired at various levels of mediocrity, his personal life appeared to be on the upswing. He became smitten with resident Columbia Studios love goddess, Rita Hayworth. Admiring her beauty, Welles ambitiously courted Hayworth under the watchful eye of Columbia studio chief, Harry Cohn, who broached the union with minimal trepidation in the hopes that it would fast fizzle. Instead, Welles and Hayworth married on September 7, 1943.

MGM offered Welles an opportunity to direct and costar as the spurious man of mystery in The Stranger(1946), typecasting that would stick with similar parts in Tomorrow Is Forever (1946) and later, Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949). Determined to deliver a commercially viable film on time and under budget, The Stranger proved to be Welles’ only profitable project. Yet, it is an artistically unsatisfying addition to his film cannon and lacks his inimitable savvy for inventive staging, mood and setting.

At this junction in his career, Welles began dividing his time between Hollywood and New York. His latest Broadway venture was an expensively mounted co-production with producer/showman Michael Todd: Around the World in Eighty Days. Unfortunately for the pair, midway through the planning stages, Todd ran out of money. Enter Harry Cohn with an offer to secure Welles services for another thriller along the lines of The Stranger. Welles reportedly gambled with Cohn to secure money needed to complete his venture with Todd. In return, Welles agreed to produce, direct and star in The Lady from Shanghai (1947); a macabre thriller based on the novel ‘If I Die Before I Wake.’ The project began in earnest and mutual respect but quietly degenerated into confusion and debacle behind the scenes.

Rita Hayworth was cast as Elsa Rosalie Bannister against Welles objections. He had conceived the film as a low budget thriller. However, Hayworth’s participation ensured two criteria – first; that the film would have to be mounted on a more ambitious scale, and – second; that the plot would need to conform more steadily to the public’s expectations from a Hayworth Grade-A movie.

On the home front, Hayworth and Welles’ stormy marriage had quietly disintegrated prior to pre-production. Hayworth had hoped that working together would reunite them romantically. To this end, she even allowed Welles to cut and dye her trademark red tresses blonde. When Harry Cohn discovered this alteration he was furious, openly grumbling that “I’ll never do this again. What’s the point of allowing a man to be director, star and producer? I might as well be janitor!”

However, Cohn lavished more concern over the film’s spiraling budget and what he perceived to be Welles over indulgences on insignificant aspect of the production. For example, Welles had originally conceived an elaborate funhouse sequence to round out the film’s climactic confrontation between Elsa and Michael (his character). The sequence incorporated some very bizarre visual elements, including a room entirely constructed from dangling arms and a half decapitated skull with a blonde wig and cigarette vaguely resembling Hayworth’s character. These details were supplied by Welles, who actually devised and painted portions of the funhouse set himself. Cohn thought the added expense extremely wasteful.

Welles’ rough cut on The Lady from Shanghai ran nearly two and a half hours – a last straw in excess that Harry Cohn would simply not tolerate. Relieving Welles of his directorial duties, Cohn had his own editor hack into the film with ruthless indecision, reducing its running time to barely 98 minutes and cropping the aforementioned funhouse sequence to a brief ‘hall of mirrors’ finale. The Lady from Shanghai was released to tepid box office response and ruthless reviews. Yet, the legend and myth surrounding The Lady from Shanghai, that it “cost a fortune, lost a fortune and ended Welles’ career at any of the major studios” is quite false.

In reality, the film cost no more than any other Rita Hayworth film of the period. While it is true that The Lady from Shanghai was not a financial success, in Hollywood the failure did little to curb Welles’ popularity as an actor. He appeared in Othello (1952), staged a low budget version of King Lear (1953) for television, appeared to good effect in the cult classic, Mr. Arkadin (1955) and even found time to host and star in an episode of television’s Ford Star Jubilee. What is undeniable about The Lady from Shanghai is that it proved the final undoing of the Welles/Hayworth union. The couple were divorced on December 1, 1948. The film also marked the second to last time Welles would be allowed to direct, produce and star in a project of his own choice.

“Movie directing is the perfect refuge for the mediocre.” – Orson Welles

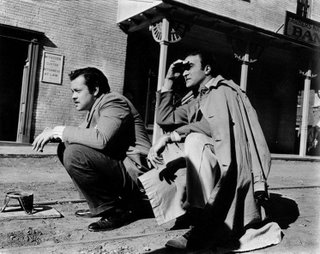

That final venture in front of and behind the camera was Touch of Evil (1958) for Universal Studios. Yet again, the plague of mediocrity fell upon him. Despite the fact that some of Hollywood’s most popular talents (Charlton Heston, Janet Leigh, Akim Tamaroff, Marlene Dietrich and Zsa Zsa Gabor) rallied their considerable talent and time on the project, Welles’ preceding reputation as a tyrannical force of nature eventually forced his dismissal during post production. The film was re-edited according the studio’s likes and unceremoniously dumped on the market to abysmal public response. Welles Hollywood tenure had officially come to an end.

“I hate television. I hate it as much as I hate peanuts. But I can’t stop eating peanuts.”

– Orson Welles

Appearing sporadically on television, most noticeably as a magician in Hollywood's Magic Castle and as a guest on I Love Lucy, Welles became something of a public recluse – his weight the brunt of jokes on The Tonight Show, his connoisseur’s palette exploited for commercial endorsements. “My doctor told me to stop having intimate dinners for four,” Welles regularly mused, “Unless there are three other people.” Throughout the 1950s, Welles made several valiant attempts to launch himself in independently funded projects, including a film adaptation of Don Quixote. But these were either scrapped prior to completion or outwardly rejected by the changing powers in Hollywood.

One of Welles last notable film appearances was as Cardinal Wolsey in Fred Zinnemann’s Oscar winning, A Man for All Seasons (1966) – an all too brief but nevertheless brilliantly realized performance. In 1971 the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences bestowed an honorary Oscar on Welles for ‘superlative artistry and versatility in the creation of motion pictures’ – an epitaph bitterly at odds with Welles costarring status in Jim Henson’s The Muppet Movie (1979). Reflecting on his award, Welles admitted, “Now I am an old Christmas tree, the roots of which have died. They just come along and while the little needles fall off, replace them with medallions.”

In his final decade, Welles increasingly appeared as a narrator on television or as the self-deprecating wit of fine wine and any other product that required a Hollywood relic to endorse it. “I have an early call tomorrow,” Welles once told a reporter, “For a commercial. Dog food, I think. No, I do not eat from the can on camera but I celebrate the contents. Yes, I have fallen that low.” Welles was also one of the first Hollywood alumni to be outspoken against the process of colorizing black and white movies. “Keep Ted Turner and his goddamn Crayolas away from my movies!” he said. He died of a heart attack on October 10, 1985 at age 70.

The Time Has Come for Parting…

“I passionately hate the idea of being with it. I think an artist has always to be out of step with his time.”

– Orson Welles

Inevitably, the legacy of Orson Welles focuses on Citizen Kane – the film once criticized as too controversial but since praised regularly as the greatest American movie of all time. More recently, The Magnificent Ambersons has risen in critical estimation; and there is much to recommend The Lady from Shanghai as well. Yet, few pause to ponder Welles beyond films or recall that his genius was further reaching than the art of motion pictures.

To be certain, after conquering the venues of live theater and radio, movies represented a logical extension for Welles’ formidable talents in 1940.

“I started at the top,” Welles would later explain, “…and worked my way down.”

Kane is a grand experiment; a film truly ahead of its time. But Welles ultimately became the embodiment of greater triumphs that sadly, did not materialize. In the final analysis, the character of Charles Foster Kane foreshadows the life of Orson Welles more readily and with greater accuracy than it does William Randolph Hearst’s. Kane illustrates, perhaps with divine perversity, how greatness at varying strengths, conviction and blind determination can be so easily dismantled with one fell swoop of mediocrity’s mighty hand.

“A film is never really any good…” Welles once said “…unless the camera is an eye in the head of a poet.”

Orson Welles illustrated that point with at least one definitive classic.

2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment