The Early Anatomy

of a Showman

by Nick Zegarac

It has been said of showmen, that they uniformly possess three inherent qualities which make them indelible titans: blind courage coupled with a gambling spirit, especially in the face of certain debacle; tyrannical drive to reinvent and elevate themselves from humble beginnings; and, a crass dispensation for the niceties of everyday life. One might also ascribe an innate sense of smug superiority to this roster. Certainly, these criteria hold true for Michael Todd.

Born Avrom Hirsch Goldbogen in Minneapolis Minnesota on June 22, 1909, Todd had already gambled, made and lost a fortune as the purveyor of bad taste with a series of girlie stage spectacles. Reportedly something of a rough hewn bruiser and ladies man, Todd relied heavily on these myths about his reputation to remake himself larger than life. Ever the adroit promoter, when it was suggested that he may have had something to do with his first wife Bertha Freeman’s mysterious death, Todd willingly played into the obscurity of the allegations, confident that even scandal could only serve to advance his career. If it was timing that ultimately made Mike Todd rich and famous – then timing he most definitely had. For Todd was involved with mistress, actress Joan Blondell at the time Bertha died. He eventually married Blondell on July 5, 1947, barely a year later.

Through sheer will and colossal cheek, Todd transformed his carnival-esque background into that of a boorish Broadway impresario, responsible for launching an expensive but abysmal failure with his stage version of Around

the World in 80 Days in 1946. Ironically, this Jules Verne property would become his greatest personal triumph as a film producer a scant ten years later.

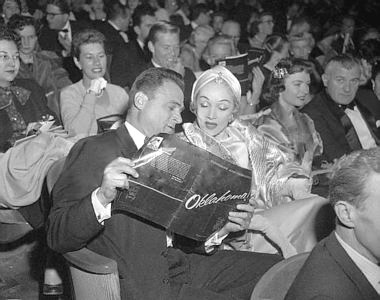

the World in 80 Days in 1946. Ironically, this Jules Verne property would become his greatest personal triumph as a film producer a scant ten years later.Frequently living beyond his means, Todd twice went bankrupt; first as a young man during the Great Depression with a $1 million deficit derived from his construction business, then again at the cusp of the 1950s, when his spiraling debts incurred through gambling and wanton spending threatened to overwhelm him. Yet, two great salvations came Todd’s way at precisely this moment in his precarious perched career; the first was violet-eyed actress and soul mate, Elizabeth Taylor. The other was Todd A-O; the invention that reinvented Michael Todd as Hollywood’s newest zeitgeist.

…of ‘scope’ and quality

20th Century’s Fox wins the race

In 1954, 20th Century-Fox production chief, Darryl F. Zanuck shocked the film industry with the debut of Cinemascope – an anamorphic widescreen filming and projection process, designed to lure back the movie’s dwindling market share from television.

Despite the fact that there was nothing new about Zanuck’s launch (for Henri Chrétien’s process had been around and even tested since the late 1920s and early 30s, and there had even been sporadic attempts to expand the size of theater screens ever since; though none had proven more successful to that point than Cinerama stunning debut in 1952), Mike Todd remained unconvinced of ‘scope’s’ supremacy. However, the rest of Hollywood struggled to catch up. Many moguls merely opted to pay Zanuck and Fox under a rental agreement for the ‘loan out’ of Cinemascope lens and equipment. Todd had very different ideas.

After all, Todd was, among his many ventures, a heavy stockholder and initial investor in Cinerama – the widescreen wonder that had started it all. But with Cinemascope’s unexpected and very sudden burst in popularity Cinerama suffered a proportionate downturn in public interest and lack of studio investment to produce new films in the three camera process.

For Todd, the problem was not simply that he had been outplayed in the forum of popular opinion, though it must have upset his gambler’s lucky streak to be outdone and undone so quickly by a competitor. Despite its ease of operation, especially when compared to Cinerama’s cumbersome three-camera setup, Cinemascope’s promise of widescreen spectacle was less appealing for Todd because it failed to capture the vibrancy in color and sharpness that Cinerama had easily reproduced.

The sharpest portion of a projected Cinemascope image was its middle, with a gradual and rather obvious blurring of the image it advanced to the outer edges of the screen. Fox had been clever to time its shots accordingly so that audiences were rarely given the opportunity to critique these discrepancies in image quality. Hence, while the economy of Cinemascope interested Todd greatly, the overall quality of the image failed to live up to his weighty expectations.

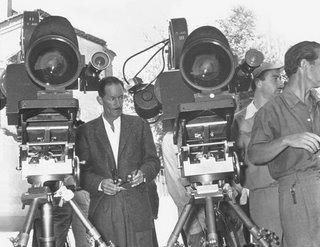

Divesting himself of his Cinerama stock, Todd approached Massachusetts’ American Optical developer and CEO, Brian O’Brien with a $100,000 check to finance a new and improved photographic process Todd himself crudely dubbed as “Cinerama out of one hole.” After considerable debate and gestation, O’Brien and Todd decided that their new venture would incorporate a combination of technical elements that had been around since the late 1920s.

During the depression and war, 65mm film gauge had been considered a wasteful extravagance. But with the newly infused capital of the booming 1950s, 65mm was resurrected from its historical oblivion along with the Mitchell BFC camera that had been in mothballs since 1931. Unlike conventional movie cameras, which photographed action at 24 frames per second (fps), the Mitchell recorded its visual information at 30fps, thus producing a sharper flicker-free image. For Todd the improvement in clarity was a sideline to his centralized fascination for the ninety pound, 12.7mm ‘bug-eye’ lens that virtually captured the same 128 degree vista as three-camera Cinerama.

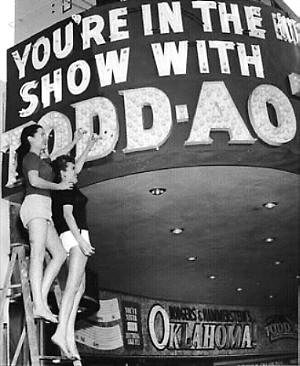

Heavily influenced by Todd’s lingering aspiration to duplicate the intricate precision of Cinerama’s projection, his newly christened process, Todd A-O (Todd American Optical) featured a deeply curved screen and stereophonic sound system almost identical to Cinerama’s, with specially rectified prints made exclusively for theatres where normally high projection booths would have otherwise resulted in considerable dimensional distortions on the screen.

No comments:

Post a Comment