Like most producers, Joseph Pasternak preferred to showcase familiar talent that he admired in subsequent projects. While Gene Kelly’s constant reinvention of his character and dance steps ran into some minor conflict with Pasternak’s ‘just shoot it’ approach, the producer’s mutual respect for soprano Kathryn Grayson ensured that the two would reunited on subsequent projects. Kelly’s own bravado may have only been partly to blame. Moreover, it was his contemporary stylistic approach that Pasternak probably found off putting.

Pasternak followed Anchors Aweigh with a minor – if delightful – musical, Two Sisters from Boston (1946) in which Kathryn Grayson’s aspirations of becoming an opera singer are realized only after she lies to her family about having already risen through the ranks onto greatness. The film costars winsome June Allyson and stoic Metropolitan Opera’s Heldentenor, Lauritz Melchior whom Pasternak had showcased previously in The Thrill of Romance and would use again in support on Luxury Liner (1948).

Pasternak’s final offering for 1946 was Holiday in Mexico, the final collaborative effort between him and director George Sidney. It was a frothy epically mounted super-production that capitalized on the U.S.’s fascination with Latin music. The film costars Walter Pigeon as Jeffrey Evans, an ambassador whose precocious daughter, Christine (Jane Powell) becomes the subject of great concern when she launches into a humorously misguided affair with her much too old for her idol, Jose Iturbi. Adopting the same star-making principles as he had done with Deanna Durbin, on this occasion Pasternak was given very solid material in the personage of Jane Powell. Winsome, adorable and a superior actress to Durbin, Powell’s rendition of the light classics (including Ave Marie - sublimely executed as a candle lit processional with an ensemble of several hundred) made the film an outstandingly visual landmark musical.

For the next two years Pasternak’s production unit was the busiest on the MGM lot – second only to Arthur Freed – indulging his every whim in lightweight popular entertainments that often showcased Powell, Melchior and Grayson. Powell in particular had one of her biggest successes with Pasternak’s A Date With Judy (1948) in which she sang the Oscar winning, It’s A Most Unusual Day. Pasternak also found a moment to produce one of Judy Garland’s minor projects; In The Good Old Summertime (1949). A musical remake of The Shop Around the Corner (1940) ‘Summertime’ cast Garland as Veronica Fischer – a shop girl whose love for a secret admirer is equaled by her disgust for boss, Andrew Larkin (Van Johnson); both the same person. Admittedly Pasternak’s fiery disposition had been known in the past to get the better of him with temperamental stars. Garland was at this point in her career famous for absences from the set. However, Pasternak’s overwhelming respect for Garland as a talent and his empathy for her as a commodity of the studio system on this occasion prevailed.

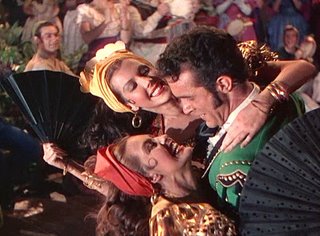

Pasternak’s one misfire from this vintage was The Kissing Bandit (1948), an erroneous and miscast fable that told the tale of a demure countryman, Ricardo (Frank Sinatra) who is expected to take up his family’s honor by following in his father’s footsteps as a rapscallion with the ladies. Delightfully obtuse, but marred by a rather lackluster score (its one musical salvation, the erotic Dance of the Furies performed by Ricardo Montalbaun, Ann Miller and Cyd Charisse) and changing audience tastes, the film was an abysmal financial and critical flop at a time when Arthur Freed’s career was just beginning to enter its golden period. With the debut of The Kissing Bandit, the balance in the professional rivalry between Pasternak and Freed – which had thus far been on par, appeared to have shifted awa

y from Pasternak’s favor.

y from Pasternak’s favor.Although his projects had already begun to bear the hallmark of ‘tried and true’ to the point of becoming repetitiously similar, Pasternak would round out the decade with a new find – one worthy of discovery. A star of the first magnitude debuted when Mario Lanza took center stage opposite Kathryn Grayson in That Midnight Kiss (1949). A schmaltzy semi-autobiographical account of Lanza’s own rags to riches story, the film cast the diminutive tenor as truck driver Johnny Donnetti. The fact that within the context of the story Donnetti was destined not to remain a truck driver for very long proved secondary to the earth shattering vocals Lanza provided for the film. His duets with Grayson, ‘They Didn’t Believe Me’ and ‘Love is Music’ drew crowds around the block and once again resurrected musical operetta from the dustbins.

Seemingly secure in his ability to create successors to the mantel of MGM’s most popular operatic team; Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy, Pasternak reteamed Lanza with Grayson one year later for The Toast of New Orleans (1950) a film in which the operatic duo severely clashed off stage, despite warbling the romantic pop tune ‘Be My Love’ with convincing passion on screen. Lanza’s swollen ego was perhaps partly to blame, but Grayson emphatically refused to work with him again and tragically, never did.

In the early 1950s, Pasternak bid farewell to several lucrative associations which had established his career at MGM. The first of these was his sad goodbye to Judy Garland. Her erratic behavior brought on by a chronic addiction to studio sanctioned prescription sedatives and weight loss drugs had effectively dismantled Garland’s reputation on the backlot from total professional to unmitigated problem.

After being replaced by Betty Hutton in Annie Get Your Gun (1950) Garland had retreated to a sanitarium for a brief rest before being assigned to the Pasternak unit for Summer Stock (1950) the film that proved to be her last at MGM. A throwback to her earlier teaming with Mickey Rooney and the ‘hey kids – let’s put on a show’ barnyard musical, Garland was cast as Jane Falbury – a country girl whose farm is invaded by show people trucked in from New York by her star struck younger sister Abigail (Gloria DeHaven).

Originally intended as a reunion film between Garland and Rooney, the latter’s star power had fallen on hard times in recent years, forcing MGM to reconsider and recast the role of Broadway producer Joe Ross with Gene Kelly. Rested, though hardly recuperated, Garland entered the production with high hopes. She quickly found it difficult to cope. Once again, Pasternak’s admiration for his star prevailed over what might otherwise have been a very ugly clash of wills.

“I had to handle her (Garland) differently than anybody else,” Pasternak later mused, “Delay with Judy is something that is within her - something you know she can’t help. Everybody at the studio said to me: ‘How can you stand these delays?’ I replied: ‘When I look at the rushes, I pray she’ll come back any day.”

Summer Stock would prove a resounding success for both Garland and Pasternak and one of the few high points of the producer’s 1950s tenure. In 1951, there was only one such cause to celebrate; the opera laden glossy bio-pic, The Great Caruso for which Mario Lanza sang no less than 27 arias, occasionally accompanied by a dubbed Ann Blyth. Pasternak’s other two offerings; Skirts Ahoy and Rich and Young and Pretty were easy enough on the mind and the ear, but each came at a transitional moment in Hollywood where this sort of polite fluff was increasingly proving to find less of an audience willing to partake at the box office.

More problematic on all fronts was Pasternak’s attem

pted glossy remake of The Merry Widow (1952) that cast a non-singing Lana Turner and only moderately talented Fernando Lamas in the roles immortalized on screen in the 30s by Jeanette MacDonald and Maurice Chevalier. Undaunted by the tepid response to their teaming, Pasternak tried again one year later with Latin Lovers (1953) an infinitely better suited vehicle that did respectable box office. The mold had unofficially been broken: with few exceptions Pasternak would not return to frothy musical operettas again.

pted glossy remake of The Merry Widow (1952) that cast a non-singing Lana Turner and only moderately talented Fernando Lamas in the roles immortalized on screen in the 30s by Jeanette MacDonald and Maurice Chevalier. Undaunted by the tepid response to their teaming, Pasternak tried again one year later with Latin Lovers (1953) an infinitely better suited vehicle that did respectable box office. The mold had unofficially been broken: with few exceptions Pasternak would not return to frothy musical operettas again.Pasternak officially bowed out of producing Esther Williams popular acquacade series with Easy to Love (1953) a film shot almost entirely on location at Florida’s Cypress Gardens that looked undeniably good on the big screen. But aside from Williams lavish water ski finale there was remarkably precious little else by way of added sass or brilliance to recommend the piece. It failed to come to life, except in fits and sparks.

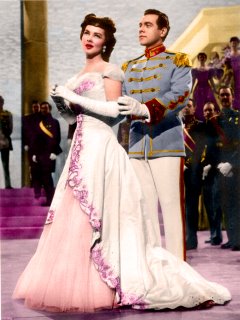

So too did the marriage between Mario Lanza and Pasternak quickly degenerate during preliminary production on The Student Prince. Lanza, whose weight was known to wildly fluctuate between film roles, had by this point become an unmanageable egotist both on and off the set. After recording all of his vocals for the pending project, Lanza was unceremoniously replaced by the more lanky Edmund Purdon whose lip-syncing to Lanza’s vocals proved quite acceptable after several strained moments of curious indecision.

The last of Pasternak’s discoveries to divest from their mutual association was Jane Powell. By all accounts she had been the most complicit and compliant of Pasternak’s protégés. However, as with most of her contemporaries, Powell’s talents as a singer had increasingly fallen on deaf ears at the box office. By the mid fifties, the Hollywood musical was in another transitional phase, buffeted by fewer original productions and a downscaling in studio investment in favor of acquiring pre-sold Broadway shows that could be transplanted to film. Pasternak’s Small Town Girl (1953) which cast Powell opposite Bobby Van and Ann Miller was enough of a diversion to reap in modest returns.

But Athena (1954); the clunky tale of two sisters, (Powell and Debbie Reynolds) who decided to open a health spa in the country proved to be a tiresome, if modest, flop. The last collaboration between Pasternak and Powell – Hit The

Deck (1955) was a celebrated and inspired musical offering, a delightful romp which attempted to resurrect the Anchors Aweigh formula that Freed had more recently exploited to good effect with On The Town (1949). The well, however, had been visited once too often. Though Hit The Deck did moderate box office it was sadly underrated, providing further proof to the ever-changing studio management that Pasternak had worn out his welcome.

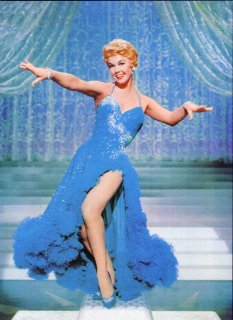

Deck (1955) was a celebrated and inspired musical offering, a delightful romp which attempted to resurrect the Anchors Aweigh formula that Freed had more recently exploited to good effect with On The Town (1949). The well, however, had been visited once too often. Though Hit The Deck did moderate box office it was sadly underrated, providing further proof to the ever-changing studio management that Pasternak had worn out his welcome.A slight reprieve came by way of Pasternak’s other musical of the year, Love Me Or Leave Me (1955). It told the embittered/embattled tale of torch singer Ruth Etting, whose marriage to mid-sized mobster Marty Snyder proves her undoing. Melodramatic, but fairly accurate in its account, the film was Doris Day’s most successful post Warner Brothers musical to date. Unfortunately for Pasternak, he followed its success with one of his worst offerings, The Opposite Sex (1956) a bizarrely charm free remake of The Women (1939) with June Allyson in the Mary Haines role immortalized by Norma Shearer. Pasternak’s next few ventures were not much better: Ten Thousand Bedrooms and This Could Be The Night (both in 1957), and, Party Girl and Ask Any Girl (both in 1958) increasingly out of touch with popular

tastes.

tastes.As Pasternak entered the more liberally minded 1960s, he continued to indulge sentimental stories with two of his best; Please Don’t Eat The Daisies and Where The Boys Are (both in 1960). The former was a featherweight but popular non-musical in which Kate (Doris Day), the wife of a successful playwright, Lawrence MacKay (David Niven), suspects that her husband may be having an affair with Broadway pinup, Deborah Vaughn (Janis Paige). The latter film has since become a time capsule for a bit of fluff and nonsense about four college girls seeking lasting love on the beach.

As for the rest of Pasternak’s 60s film output, it was a mixed bag at best, most apart from the musical genre that he had helped to cultivate and develop along side Arthur Freed during its heyday. Pasternak’s last stab at the musical was a Teutonic failure; Billy Rose’s Jumbo (1962) which attempted unsuccessfully to reunite Doris Day with the big old fashioned musical. Despite an excellent score and some fine performances, the ‘big show’ was hampered by last minute studio cutbacks that effectively reduced the film to a poor cousin to Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth (1952). In between his film work, Pasternak found time to produce three Oscar telecasts for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). An avid amateur chef he also penned the book Cooking with Love and Paprika. It was published in 1966.

Pasternak’s last noteworthy film of the decade was The Courtship of Eddie’s Father (1963) a comedy/romance directed by Vincente Minnelli that charted the course of a young Ron Howard desperately trying to align his lonely father (Glenn Ford) with a romantic liaison who would eventually become his stepmother. In his waning years, Pasternak continued to produce movies at MGM, at least attempting to tap into ‘the new music’ by producing three of Elvis Presley’s later efforts, including Girl Happy (1965).

Failing health and age effectively forced Pasternak into retirement after 1968’s The Sweet Ride. Diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, Pasternak chose to live out the remainder of his life almost in seclusion. Though he lived for two more decades it was hardly an existence wished for his emeritus years. Still, Pasternak could revel in the fact that he had produced some 90 films – most with considerable merit, all branded by his inimitable flare and zest for life itself – two worthy of Oscar nominations. He was still regarded by many in and outside of the Hollywood community to be a film pioneer in the musical genre.

On September 13th 1991, Joseph Pasternak passed away from complications of Parkinsons Disease. He was a mere six days shy of his 90th birthday. What is perhaps most noteworthy about the best of Pasternak’s musicals today is how unlike anything else of their vintage or beyond they are – as distinct as the personage of Garbo, as poignant as that throbbing intonation derived from a Garland ballad. At their best then, the films of Joseph Pasternak continue to resonate with some sort of magically infused promise for a better tomorrow; elevating mediocrity to a place where only angels from that removed and forgotten past continue to sing – their championed voices raised in exaltations far beyond the confines of the world that gave birth to them in the first place.

What remains true of a Pasternak musical, then and now, is not their adherence to time-honored traditions that became mired in the fallout of changing audience tastes, but that each film has endured the onslaught of that change – transcending the time in which they were conceived and the era – far more aged - that they hark back to. Pasternak’s movies are therefore not the pop-culture pot boilers of any decade, as often described. They are, and remain, epic tone poems relevant for all time.

@Nick Zegarac 2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment