– Max Steiner

Though many may not immediately recognize the name Max Steiner he is imbedded in the collective cultural celebration of classic Hollywood – as indelibly unique as the directorial prowess of Hitchcock or adept at stirring the emotional finesse as the terpsichorean proficiencies of Fred Astaire.

Even today, the contributions of film score composers remains an almost forgotten and most regularly overlooked enigma in the process of creating screen art. But in Steiner’s time the contributions of many of his contemporaries was practically invisible. If, as composer Max Steiner suggests, an entire world history exists in every man, then his personal history in score and song has been the most glorious romanticized adventure we are ever likely to know.

Born Maximillian Raoul Walter Steiner in Vienna, Austria on May 10, 1888, Steiner came by his craft with all the rich endowments of that ancient flower: high European artistry in musical composition, and with an affluent background in theatrical endeavors.

Both his grandfather and father favored the theatrical arts. Steiner’s father, Gabor actually became a lucrative producer of operettas. As a child, Max Steiner was immersed in composition studies at Vienna's famed Hochschule Music Academy. In fact, he completed his four year program in little over a year – a prolific efficiency that would serve him well once installed in Hollywood.

By the age of 16 Steiner had already composed an original operetta, The Beautiful Greek Girl. Ironically, Gabor’s lack of enthusiasm in the son’s project led Max to negotiate a lucrative deal with his father’s competitor. He conducted the show’s opening night performance. The show ran for a solid year. It was the beginning of greatness.

In four short years, Steiner would be critically hailed as a musical genius. Feeling that his future would best be served by a move, Steiner traveled to London England, but soon became dissatisfied with his decision. He immigrated to New York where he quickly became one of the top orchestral arrangers on Broadway, working for the elite; Victor Herbert, the Schuberts and Florenz Ziegfeld. Steiner also conducted original productions for Irving Berlin, George Gershwin and Jerome Kern.

GOING HOLLYWOOD

“There is nothing more effective in motion picture music than sudden changes in mood cleverly handled, providing, of course, they are consistent with the story”

– Max Steiner

By 1929, his popularity on the Great White Way had garnered the attentions of Hollywood. William LeBaron, then head of production at RKO, hired Steiner as musical supervisor on the film version of Rio Rita. It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship. Steiner remained at RKO for the next seven years contributing fanfares and musical cues for some of the studio’s top melodramas, comedies and musicals. He also inherited an early personal success after Jerome Kern turned down the opportunity to write the score for Cimarron (1931). Though he received no screen credit for his efforts, Steiner’s music was celebrated by musicologists.

However, it should be pointed out that Cimarron represented a departure for Steiner and not the norm. During this tenure at RKO Steiner wrote mostly main

and end title music for features while his contemporary Alfred Newman had already scored Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights (1931) and was then experimenting with dramatic music for Samuel Goldwyn's Street Scene (1931).

and end title music for features while his contemporary Alfred Newman had already scored Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights (1931) and was then experimenting with dramatic music for Samuel Goldwyn's Street Scene (1931).In 1932 RKO experienced a minor corporate shakeup. Passionate and power driven future mogul in the making, David O. Selznick was now in charge of production. Impatient to alter the chemistry of the studio’s film output, Selznick’s first move was to employ Steiner’s musical prowess for several dramatic sequences in Gregory LaCava’s Symphony of Six Million (1932).

However, film scoring was a concept new to most of his executive board who thought it extravagant and wasteful to employ a composer for such a lengthy endeavor. To help bolster his stance on the project, Selznick had Steiner provide a sample score for the first reel – a scene where actor Gregory Ratoff’s character undergoes an unsuccessful operation. His decision and Steiner’s stealth as a composer easily made believers from those same set of skeptics. Steiner went on to score the rest of Symphony of Six Million and was shortly thereafter assigned to King Vidor's Bird of Paradise (1932, right); the first full score Steiner actually wrote, earning him the moniker of ‘Dean of Film Music’.

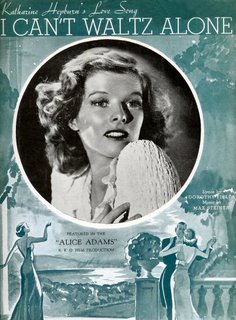

Steiner’s great gift to the new medium derived from his ability to incorporate traditional melodies with his own unique and original compositions. That seamless blending, coupled with Steiner’s infusion of the leitmotif (a Wagnerian principle in composition, whereby multiple characters are given their own distinct theme that is played whenever they enter a scene) created the hallmark for Steiner’s innovative and endearing film scores of this

vintage. Steiner’s first run of this latter concept emerged triumphant with a cue he wrote during Katharine Hepburn’s Hamlet soliloquy in Morning Glory (1933); an astute and intuitive cue that idyllically conveyed the pending solemn mood.

vintage. Steiner’s first run of this latter concept emerged triumphant with a cue he wrote during Katharine Hepburn’s Hamlet soliloquy in Morning Glory (1933); an astute and intuitive cue that idyllically conveyed the pending solemn mood.In contrast, Steiner’s buoyant cues for the 1933 version of Little Women, proved evocative strands centralized around the film’s key character of Josephine March (right), creating as it were a maypole of musical activity about which the rest of the score effervescently evolved. Steiner’s composition for Little Women proved so idyllic that when Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer remade the property in 1948, composer Adolph Deutsch’s contributions to that version were essentially limited in the creation of subtle variations on Steiner’s original material. One of Steiner’s longest and most enduring scores from the 1930s is King Kong (1933).

“This I wrote in two weeks,” Steiner would muse in an interview, “…the music recording cost around fifty thousand dollars…the studio attributed at least twenty-five percent of its success to the music.”

At 75 minutes, it remains as ambitious and all encompassing a masterwork as any from that period, with multiple themes and interwoven agitato sequences. Crucially, Steiner’s dense textuality leant an air of finite confirmation to the supernatural and a strangely sympathetic chord for the towering seventh wonder of the world. King Kong’s score is also noteworthy for the fact that it was one of those rare instances where film critics paused a moment in their reviews from that usual ignorance afforded composition to bestow their accolades on Steiner.

Perhaps wit and gifted pianist, Oscar Levant coined the brevity of the film’s score best when he wrote that “King Kong should have been billed as ‘Music by Max Steiner’ with accompanying pictures.”

Throughout the early to mid-1930s, Steiner continued to make immeasurable contributions to RKO’s film output with varying degrees of notoriety. He was involved in a supervisory capacity on several of the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musicals. He defined and sustained the air of dramatic tension so integral to The Most Dangerous Game (1932); generated a looming sense of melodramatic tragedy and empathy in What Price Hollywood? (1932), and effectively captured a genuine sense of sexual ambiguity to Katharine Hepburn’s gender-bending performance in Christopher Strong (1933).

Ever striving to expand the boundaries of film scoring, Steiner, the innovator’s musical scoring for Of Human Bondage (1934) developed a musical illustration of the club-footed Philip Carey (Leslie Howard). His contributions on John Ford's The Lost Patrol (1934) – which had been ill received without musical scoring during a sneak preview - so effectively enhanced the overall sense of adventure that Steiner was honored with his first Oscar nomination. The following year, Steiner collaborated with Ford again, this time on the tale of Irish rebellion and betrayal; The Informer. Steiner’s musical blending of overt gregariousness, evocative pseudo-ethnic themes and intricately woven subconscious effects easily won him his first Academy Award.

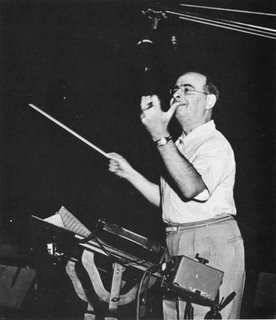

“When a picture is finished and edited it is turned over to me,” Steiner explained, “I have the film put through a measuring machine and then a cue sheet created which gives me the exact time to the split second in which the action takes place and words are spoken. While these cue sheets are being made I being to work on themes for the different characters and scenes…I also try to digest what I have seen and try to plan the music for the picture. Once all my themes are set I am apt to discard them and compose others, because frequently, after I have worked on a picture for a little while my feelings towards it change.”

Today, Steiner’s cues for The Informer have won the dubious distinction of being most often scornfully referred to as ‘Mickey-Mousing’(a term describing the oft’ heavy handed way musical compositions should not directly accompany the literal action on the screen).

The final notable composition in Steiner’s RKO canon is The Three Musketeers (1935), an 80 minute symphonic masterpiece in which Steiner received sole musical credit. But in 1936 Steiner departed RKO at the behest of David O. Selznick(right), who had recently inaugurated his own studio - Selznick International Pictures. The decampment was a mixed blessing.

Although it allowed Steiner a lull in the hectic pacing he had endured, the move also meant that Steiner would frequently have to endure Selznick’s overzealousness to meddle in his work on a creative level. For someone with Steiner’s immense talent and speed for creating masterworks, this stalemate was, if not damaging, then perhaps more tiresome than the breakneck speed he had become accustom to at RKO.

After a promising start Selznick loaned Steiner to Warner Brothers for The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) – a bold and garish composition that embodied the feisty pervasive cavalier attitude of Errol Flynn. The following year Steiner exercised his creative juices on a more subtle musical palette for the original A Star Is Born (1937). On this endeavor Steiner found Selznick’s involvement particularly meddlesome. After listening to Steiner’s compositions, Selznick began dropping cues and excising whole portions of scoring from other films to include in place of the work Steiner had committed to.

Seizing upon Steiner’s immediate dissatisfaction with Selznick, Jack L. Warner bought out Steiner’s contract under the condition that he would score one picture per annum for his old nemesis.

THE STEINER LEGACY

AT WARNER BROTHERS

“There are no rules and won’t be as long as music continues to assume more and more importance in pictures and the development of sound continues to make such rapid strides.” – Max Steiner

The thirty-year association between Max Steiner and Warner Brothers is perhaps the greatest marriage between artist and dream factory ever put on film. Beginning with his memorably defined fanfare for the famous Warner Shield in 1937 (first played before the main titles of Tovarich) Steiner’s reputation as a composer grew exponentially in leaps and bounds.

In defacto, Steiner became the ‘Warner sound’ during its most lucrative tenure. Applied at the speed of a race horse, Steiner’s compositions veered in tone and temperament from the gritty pulsating timber applied to Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), to the sprawling vast embracement of the old west, so indelibly ingrained in his score for Dodge City (1939) and the emotionally charged leitmotif Steiner scored for one of Bette Davis’ best loved and most fondly remembered weepy, Dark Victory (1939).

Yet, while the speed and variety of the Warner slate of projects, and the relative freedom afforded his creative process bode well with Steiner’s own work ethic, of all his noteworthy achievements at that studio thus far, arguably the greatest effort was put forth during this early Warner tenure came upon Steiner’s return to Selznick International for Gone With The Wind (1939); a watershed composition brimming in hearty memorable themes, intricately designed and complimentary leitmotifs, and, Steiner’s own affinity for melodic waltzes and marches.

Despite the fact that some of the lesser musical cues were

written by Heinz Roemheld and Adolph Deutsch to meet Selznick’s Christmas deadline world premiere, at 190 minutes Steiner’s compositions for Gone With The Wind are undeniably his lengthiest. Amazingly, Steiner also managed to compose all of the cues for Selznick’s other pending film project of that year – a remake of the Swedish film Intermezzo (1939) also starring Leslie Howard and in which debuted one of the most radiate and talented of soon-to-be American film stars – Ingrid Bergman.

written by Heinz Roemheld and Adolph Deutsch to meet Selznick’s Christmas deadline world premiere, at 190 minutes Steiner’s compositions for Gone With The Wind are undeniably his lengthiest. Amazingly, Steiner also managed to compose all of the cues for Selznick’s other pending film project of that year – a remake of the Swedish film Intermezzo (1939) also starring Leslie Howard and in which debuted one of the most radiate and talented of soon-to-be American film stars – Ingrid Bergman.It is one of Hollywood’s great ironies that from a film so richly entrenched in Academy Award history, that Max Steiner did not receive the Oscar for his efforts on Gone With The Wind. Despite the films’ most instantly recognizable main title set to the now immortal Tara’s theme, the Oscar went to Herbert Stothart for MGM’s The Wizard of Oz (a forgivable loss).

In truth, Steiner’s theme for Tara was a musical offshoot of something he had previously composed in 1938 for a little seen and easily forgotten melodrama entitled, Crime School. Perhaps lacking in the foresight to recognize Tara’s staying power, Steiner also employed a variation on it in They Made Me A Criminal (1939). But perhaps the greatest of irony between Steiner and the Academy came five years later, when Steiner won the Oscar for his compositions on David O. Selznick’s wartime masterpiece, Since You Went Away (1944) – a film in which no other participant took home the gold statuette.

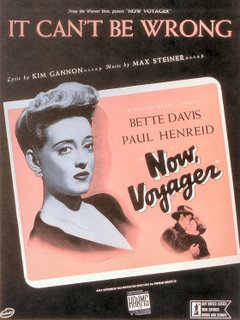

In between these two Selznick hallmarks, Steiner became comfortably entrenched at Warner Brothers where he continued to deliver magic with an impressive speed and regularity behind the scenes for a diverse cavalcade of films; The Letter (1940), Dive Bomber (1941), Sergeant York (1941), They Died With Their Boots On (1941), Casablanca (1942), Now Voyager (1942) and Mildred Pierce (1945) among many others. In the mid-1950s Steiner's unbelievable output quietly receded to a trickle, in part due to his quiet divorce from Warner Brothers that made him a freelance agent by 1954.

For nearly six years, Steiner limited himself to writing compositions for one or two pictures a year. But in 1958 he returned to Warner Brothers to score their traditional feature films and also do a bit of work in the then new medium of television.

However, many were surprised to learn that by the end of the decade Hollywood’s most prolific composer was financially ruined – thanks to Steiner’s penchant for doling out cases of brandy and cigarettes and his affinity for exercising retail therapy with the plastic. Total bankruptcy was averted when Steiner's theme song for A Summer Place (1959) became an unqualified hit, selling in excess of a million copies.

To date, only two other ‘songs’ that Steiner had written were as popular: It Can't Be Wrong from Now Voyager (1942) and As Long As I Live from Saratoga Trunk (1945). However, Warner Brothers – not Steiner – owned the rights to both of these songs. As a result, Steiner had been paid one flat fee for the entire score to both films without the benefit of royalties from repurposing both songs (which the studio liberally did in other films and its Looney Tunes cartoons). But for Theme From A Summer Place, Steiner negotiated a royalty deal that made him very rich, despite the fact that the Percy Faith recording led many to deduce that Faith, not Steiner had actually written the piece.

“Our profession is not always ‘a bed of roses’ and looks much easier to the layman than it really is,” Steiner once commented, “The work is hard and exacting and when the dreaded release date is upon us, sleep is a thing unknown.”

Still, there is little to doubt that Steiner relished that continued deadline frenzy which brought out the best in his compositions. He continued to score films until a spat with director/producer William Conrad on Two On A Guillotine (1965) effectively ended his tenure by choice.

By now Steiner was lucrative and successful enough to choose for himself and what he chose was retirement from the film industry. Steiner’s suspicions that he was no longer a composer of either great esteem or in great demand were erroneously confirmed a year later when he interviewed for a pending project on George

Custer and was obtusely asked whether he had ever scored a western. Blinded by glaucoma in his final years, Steiner passed away peacefully on December 28, 1971.

Custer and was obtusely asked whether he had ever scored a western. Blinded by glaucoma in his final years, Steiner passed away peacefully on December 28, 1971.A decade later, in July of 1980, Brigham Young University hosted an evening of film scores by Steiner to resounding applause. But more importantly, the event introduced a whole new generation to Steiner’s immeasurable contribution to American motion pictures.

Hence, while the musical men of admiration in Steiner era were Mozart, Bach, Brahms and their like, today’s aspiring composers look toward Steiner (among other luminaries of his period) for inspiration. While names like Eric Korngold, Alfred Newman and Miklos Rosza undeniably belong in that echelon, arguably its ‘Dean’ remains Max Steiner.

@2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment