by Nick Zegarac

“True yesterday, true today, true tomorrow. That’s my definition of a classic.” – Murray Burnett, playwright of ‘Everybody Comes To Rick’s.’

In 1982, writer and devil’s advocate Chuck Ross decided to conduct a minor experiment as to why Hollywood just didn’t seem to be making the kinds of films they used to. Retyping verbatim the script to Casablanca under its’ original title; ‘Everybody Comes to Rick’s’, Ross shopped the property to 217 agencies. Of the 85 who actually read and responded, 38 rejected his submission outright and only 3 thought it would make a good film. Perhaps there’s no accounting for taste – especially if you have none.

Time has indeed ‘gone by’ since the debut of one of the most beloved and enduring masterpieces in American cinema; sixty-four years to b

e exact. In that interim, Casablanca (1943) has transcended the boundaries of mere filmic entertainment to become an imbedded cultural touchstone – not only of the twentieth century, but for all time. The film’s renewed interest is as perennial as the season’s change, and, time has only served to enrich its verisimilitude in war time patriotism, dangerous intrigue and the immediacy of star-crossed lovers caught in a maelstrom of desperation and chaos.

e exact. In that interim, Casablanca (1943) has transcended the boundaries of mere filmic entertainment to become an imbedded cultural touchstone – not only of the twentieth century, but for all time. The film’s renewed interest is as perennial as the season’s change, and, time has only served to enrich its verisimilitude in war time patriotism, dangerous intrigue and the immediacy of star-crossed lovers caught in a maelstrom of desperation and chaos.But at the time the film was being made – who among the artisans involved in its craftsmanship knew that what they were involved in was destined to become cinema magic; certainly not Jack L. Warner, then head of Warner Brothers – who regarded the film as merely one in a pipeline of fifty for the pending year of slated projects. Definitely not Ingrid Bergman; uneasy on two fronts; first – because Humphrey Bogart’s then jealous wife, Mayo Methot had erroneously perceived an affair between her husband and the

luminous Swedish import; and second, because until the very final moments of shooting, it was undecided who Bergman’s character, Ilsa Lund, would be going off with; saloon keeper, Rick (Bogart) or freedom fighter, Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid).

luminous Swedish import; and second, because until the very final moments of shooting, it was undecided who Bergman’s character, Ilsa Lund, would be going off with; saloon keeper, Rick (Bogart) or freedom fighter, Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid).If it were not for the minor foresight of studio reader, Stephen Karnot, ‘Everybody Comes to Rick’s’ might have never been made. Initially, Karnot submitted a glowing 22 page synopsis of the un-produced play by Murray Burnett and Joan Allen to V.P in charge of production, Hal B. Wallis, stating,

“Excellent melodrama. Colorful, timely background,

tense mood, suspense, psychological and physical conflict, tight plotting, sophisticated hokum. A box-office natural – for (Humphrey) Bogart or (James) Cagney, or (George) Raft in out-of-the-usual roles, and perhaps, Mary Astor.”

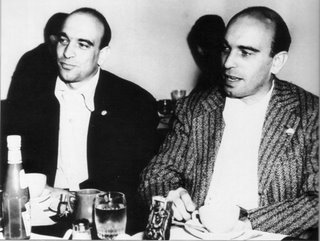

tense mood, suspense, psychological and physical conflict, tight plotting, sophisticated hokum. A box-office natural – for (Humphrey) Bogart or (James) Cagney, or (George) Raft in out-of-the-usual roles, and perhaps, Mary Astor.”Hal B.Wallis (right) mirrored Karnot’s enthusiasm. Perhaps it was his salesmanship savvy that instantly took a shine to it. Wallis was, by 1942 a self-made man whose early career as a traveling salesman had put him in contact with Sam Warner – one of the Warner Brothers. Installed in the studio’s publicity department, outside of three months Wallis was running the show. When Sam died, Wallis was promoted by Jack Warner to full fledged producer – in effect inheriting the mantel of gritty crime serials and frothy Busby Berkeley musicals from Darryl F. Zanuck – who had departed the Warner backlot to co-found 20th Century Fox.

On January 12, 1942, Warner Brothers paid the most ever for an un-produced property - $20,000 for the rights to make the film. Wallis also solicited a litany of popular opinion from his contemporaries on the backlot to help bolster interest in his pet project. Of these solicitations, only Jerry Wald’s suggestion that the script be tailored along the lines of another movie, Algiers (1938) was eventually incorporated. Writer, Robert Buckner’s opinion proved the most cynical, even going so far as to label the story’s protagonist “two parts Hemingway, one part Scott Fitzgerald, and a dash of café Christ.”

For his part, the author of the play, Murray Burnett had penned ‘Everybody Comes to Rick’s’ while touring Europe with his wife. While in the south of France, Burnett and his small party of friends attended Kat Ferrat, a nightclub where a black man warbled pop songs of the day at a piano. In a moment of inspiration Burnett confided, “wouldn’t this be a great setting for a film?”

So it was, and Wallis set about the arduous task of casting the film from Warner’s roster of contract talent. Confusion remains over the initial choices in casting. As screen writers Julius and Philip Epstein began hammering out the snappy dialogue between the principles, an article appeared in the January’s Hollywood Reporter that clearly states Ann Sheridan, Ronald Reagan and Dennis Morgan as Casablanca’s headliners. Possibly, Wallis was under the gun

to announce a cast – any cast - for his pending project. However, in years to follow, Ronald Reagan would deny that he was ever consulted or even approached to star in Casablanca. There also seems to be little doubt that Ingrid Bergman was Wallis first choice for the pivotal role of Ilsa Lund from the start.

to announce a cast – any cast - for his pending project. However, in years to follow, Ronald Reagan would deny that he was ever consulted or even approached to star in Casablanca. There also seems to be little doubt that Ingrid Bergman was Wallis first choice for the pivotal role of Ilsa Lund from the start.Stephan Karnot’s initial recommendation of Humphrey Bogart for the lead left something to be desired – at least, in the minds of Warner executives – since the actor had yet to be cast as a romantic lead. To date, Humphrey DeForest Bogart’s screen image had been that of a derelict or criminal doomed to assassination before the final reel; variations on the Duke Mantee character he had made his own in The Petrified Forest (1934). After a bit of coaxing in the front office, Wallis secured Bogart’s participation on the project – rechristened Casablanca to evoke a sense of the sensual far off mystery that had made Algiers (a 1938 similarly based film costarring Hedy Lamarr and Charles Boyer) such a resounding success.

Wallis also pursued a campaign to secure Ingrid Bergman’s participation. Bergman, who had made a stunning success of David O. Selznick’s English remake of Intermezzo (1936) and had also been exploited to great effect as the subdued but sluttish barmaid, Champagne Ivy in MGM’s remake of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941) was currently riding a crest of overwhelming popularity.

owever, she was also under an iron clad contract to Selznick. To set his wheels in motion, Wallis finagled a meeting between the Epstein Brothers and Selznick at the Selznick Studio. As Julius Epstein later recalled, during the entire first half of their meeting, Selznick seemed more preoccupied with a bowl of soup than in their taut dramatics being unfolded for his benefit. Eventually, however Selznick agreed to the loan out of Bergman, leaving Wallis to pursue the third lead in Casablanca from Warner’s roster of contract players.

Enter Paul George Julius von Henreid – the Viennese leading man currently cast opposite Warner mega-star, Bette Davis in Now Voyager. Henreid had entered the Hollywood mélange at a time when suave European Lotharios were all the rage amongst film fans. He was a protégée of agent, Lew Wasserman and an RKO contract player of some merit, whose reputation grew incrementally with each subsequent film in which he appeared. By 1942, Henreid was, if not on the same level in terms of popularity as his current costar Bette Davis, then in a far more secure place professionally than Humphrey Bogart. Hence, when initially petitioned for the third billed role of freedom fighter Victor Laszlo by Hal Wallis, Henreid politely declined the offer until Wallis agreed to costar billing and a reworking of Henreid’s part.

The backdrop of secondary characters in the film would be fleshed out by Warner’s top contract players including the formidable Sidney Greenstreet as the unscrupulous Signor Ferrari, loveable S.Z. Sakall as Karl, the waiter, and the inimitable Claude Rains as womanizing police prefect, Captain Louie Renault.

Of these, Rains represents a bizarre anomaly within the film community; a character actor who most readily appeared in supporting parts in almost every major Warner film of that period, but who also occasionally transcended his moniker as a ‘character actor’ to star in leading roles, most notably in Universal’s The Invisible Man (1933) and that studio’s pending remake of The Phantom of the Opera (1943).

To direct Casablanca, Hal Wallis assigned resident workhorse, Michael Curtiz (right). The Hungarian born zeitgeist was a man of many great ideas but very few patience. Irascible but dynamic, Curtiz had been chiefly responsible for some of the studio’s most successful and enduring films. He had helped mold the rough hewn talent of Errol Flynn from his first venture, Captain Blood (1935) to the actor’s greatest success, The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). Indeed, Curtiz was the busiest man on the Warner backlot. However, on Casablanca his penchant for threadbare tolerance was tested on more than one occasion.

By all accounts, Casablanca was a project mired in perpetual chaotic planning. The Epstein brothers (right)had barely finished the first half of their screenplay when they were called away to work on Frank Capra’s wartime patriotic documentary series, Why We Fight. Dividing their time between these projects and Casablanca greatly slowed the pace of their output.

To compensate for their absence, Hal Wallis hired resident screenwriter Howard Koch to help fill in the blanks. However, upon further consideration of the script, Wallis

also turned to Casey Robinson to bolster the romantic elements of the story which had been truncated thus far in favor of the anti-Nazi propaganda angle. Robinson’s great contribution to Casablanca was its Paris flashback sequence. In the brief span of fifteen minutes, Robinson managed to summate the emotional depth of an intimate relationship on the verge of total eclipse. The flashback also features one of the film’s best remembered lines; Bogart’s tenderly affectionate, “Here’s looking at you, kid.”

also turned to Casey Robinson to bolster the romantic elements of the story which had been truncated thus far in favor of the anti-Nazi propaganda angle. Robinson’s great contribution to Casablanca was its Paris flashback sequence. In the brief span of fifteen minutes, Robinson managed to summate the emotional depth of an intimate relationship on the verge of total eclipse. The flashback also features one of the film’s best remembered lines; Bogart’s tenderly affectionate, “Here’s looking at you, kid.”Perhaps, in part, due to Mayo Methot’s constant jealous scrutiny, Humphrey Bogart avoided any personal contact with his leading lady either in between takes or off the set throughout the entire shoot. Distraught over her inability to better understand the man she is supposed to be in love with, Ingrid Bergman screened The Maltese Falcon (1941) as research. Of her professional working relationship with Bogart, Bergman would later comment, “I kissed him, but I never knew him.” While this sort of backstage ambivalence may have seemed awkward, on camera it managed to generate sparks of turgid animosity that effectively translated to frustrated romantic love.

Of the film’s pivotal romantic climax, in which Ilsa confronts Rick in his upstairs apartment – demanding the letters of transit at gunpoint, only to be reduced into a passionate embrace - the Epstein brothers were confronted by the Breen Censorship Code and asked to remove any reference that would imply Rick and Ilsa had spent the night together. To appease this request, the Epstein’s inserted a brief shot of a light atop the airport tower rotating in the foggy night, hence establishing a passage of time sufficient enough for audiences to draw their own conclusion about what had transpired between the two ex-lovers.

Casey Robinson’s treatment of Rick and Ilsa’s love affair was further fleshed out by resident composer Max Steiner’s lush and evocative scoring. Like Michael Curtiz, Max Steiner was a talent and a commodity relentlessly pursued within the Hollywood community.

Initially, Murray Burnett had written his choices of music for the film in the margins of his screenplay. These included ‘As Time Goes By,’ a 1931 song that had little impact on the hit parade of its day. In scoring Casablanca, Steiner interpolated refrains of ‘As Time Goes By’ throughout the film even though he had been told that the song might be excised from the final cut. However, the deftness with which Steiner managed to make the underscoring of the song central to the film’s overall dramatic and romantic themes ensured that ‘As Time Goes By’ would remain in tact.

No comments:

Post a Comment