“I’m really lost about Esther Williams’ work in the movies. But if nothing else they had to be terribly dangerous.” – Time Magazine review for Million Dollar Mermaid (1952).

Today, Esther Williams would be among the first to admit that any snap analysis of her career as a serious actress is ‘all wet.’ “All they ever did for me at MGM was change my leading man and the water in my pool.” Though she was a ravishing beauty, seemingly flawless (at least on the surface) and groomed in the halcyon days of the star system, still waters ran very deep in both Esther’s life and career.

Her open admission that, at the behest of Cary Grant, she attempted radical psychotherapy with LSD (then a legitimate prescription medication) to alleviate depression is but one of Esther’s many no nonsense reflections. Of her three pragmatic divorces from husbands Leonard Kovner, Ben Gage and Fernando Lamas, Esther has since reassessed her “naïve expectations, misplaced trust, passionate love and need for a safe haven.” She has emerged like that on-camera persona of the sea nymph with

formidable stealth above and below the waterline, a resilient and vital woman of perennial youthfulness and frank sophistication.

formidable stealth above and below the waterline, a resilient and vital woman of perennial youthfulness and frank sophistication.“I don’t know to this day how I managed to fit into those bathing suits when I was pregnant…diving off platforms with Ben (her first son) in Neptune’s Daughter, going underwater in silver lame with Kim (her first son) in Pagan Love Song and learning how to water ski with Susie (daughter) in Easy to Love…and somehow I stayed a size ten through it all.”

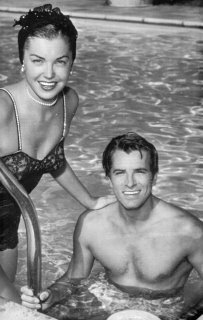

Born in Los Angeles on August 8, 1922, Esther Williams grew up with an innate love of swimming fostered by frequent visits to her local playground pool and beaches. By age 16 she had

already racked up three national championships. Although she qualified for the 1940 Olympics, the encroachment of World War II forced a cancellation of the games and Esther’s hopes for international fame as a swimmer. Cheesecake photos taken for local newspapers caught the eye of legendary showman Billy Rose who co-starred Esther with another hopeful, Johnny Weismuller in his lavish San Francisco Aquacade.

already racked up three national championships. Although she qualified for the 1940 Olympics, the encroachment of World War II forced a cancellation of the games and Esther’s hopes for international fame as a swimmer. Cheesecake photos taken for local newspapers caught the eye of legendary showman Billy Rose who co-starred Esther with another hopeful, Johnny Weismuller in his lavish San Francisco Aquacade.The overwhelming success of this

spectacle was not lost on MGM executives and talent scouts who offered Esther a screen test. As with a host of starlets that had gone before her (Judy Garland, Ann Rutherford, Lana Turner), Esther’s film debut was in a minor cameo opposite Mickey Rooney in Andy Hardy’s Double Life (1942). However, when screen scenarists approached the front offices with the concept of an entire film built around a swimmer (Bathing Beauty) the idea was met with skepticism from L.B. Mayer.

spectacle was not lost on MGM executives and talent scouts who offered Esther a screen test. As with a host of starlets that had gone before her (Judy Garland, Ann Rutherford, Lana Turner), Esther’s film debut was in a minor cameo opposite Mickey Rooney in Andy Hardy’s Double Life (1942). However, when screen scenarists approached the front offices with the concept of an entire film built around a swimmer (Bathing Beauty) the idea was met with skepticism from L.B. Mayer.“How the hell do you make pictures in a pool?” Mayer reportedly asked. “The same way Darryl F. Zanuck does with Sonja Henie and ice skates,” he was told.

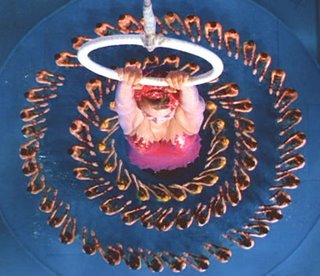

In the retrospective echelons of screen musicals, Bathing Beauty has since proven to be a minor sensation. At the time of its release it was both a colossal critical and commercial success – second only in box office returns to 1944’s reissue of Gone With The Wind. But contrary to popular rumor, it was not the first time a poolside spectacle had been attempted for the movies. That accolade falls first to Samuel Goldwyn’s The Kid From Spain 1932, and then

Warner Brothers Footlight Parade (1933). The irony of having Williams water ballets staged by the man responsible for these lavish water sequences – Busby Berkeley – was not lost on L.B. Mayer who, though a gambling man, always believed in hedging his bets.

Warner Brothers Footlight Parade (1933). The irony of having Williams water ballets staged by the man responsible for these lavish water sequences – Busby Berkeley – was not lost on L.B. Mayer who, though a gambling man, always believed in hedging his bets.However, Bathing Beauty (1944) did feature the first ‘water ballet’ in Technicolor; a splashy sequence involving fountains and fire, and a veritable army of swimmers bedecked in epic kitsch. The overwhelming success of the film launched Williams’ career as a movie star, making her the number one pin-up girl in the country and the most popular entertainer amongst film exhibitors for nearly two decades and 26 films.

“I always thought every picture I made was going to be the last one,”

Williams mused. However, what is often overlooked about Esther Williams – the performer, is the fact that she is far more than a one note wonder. True, her forte was swimming. But she was also a spirited and vivacious dancer, a convincing dramatic actress and one of the wittiest raconteurs ever to appear on or off camera. Her adept comedic styling elevated many a mundane and conventional plot and, since her tenure at MGM, have made for colorful reflections about the film industry.

Williams mused. However, what is often overlooked about Esther Williams – the performer, is the fact that she is far more than a one note wonder. True, her forte was swimming. But she was also a spirited and vivacious dancer, a convincing dramatic actress and one of the wittiest raconteurs ever to appear on or off camera. Her adept comedic styling elevated many a mundane and conventional plot and, since her tenure at MGM, have made for colorful reflections about the film industry.At MGM, Esther was given few opportunities to dry off. The public’s demand to see her in ever-increasingly lavish and more complex water ballets even necessitated the inclusion of a very brief and restrained pool sequence in the period musical, Take Me Out To The Ballgame (1949). By 1950, Esther had been effectively christened America’s Mermaid. Capitalizing on that moniker, MGM exploited her to spectacular effect in the biopic of Australian swimming sensation Annette Kellerman: Million Dollar Mermaid (1950). But the film also presented Esther with her first brush with death.

To date, every one of her underwater sequences had been meticulously pre-planned and storyboarded to allow Esther ample time to dive below surface, h

it her mark and then come up for air. However, at the behest of Williams the sequences in Million Dollar Mermaid were stacked together, occasionally two or three at a time so that she would hold her breath for increasingly longer intervals. During one of these stacked sequences, Williams discovered what divers refer to as ‘the rapture’ – a sudden compression of the lung tissue that does not allow for more air to enter its passage ways.

it her mark and then come up for air. However, at the behest of Williams the sequences in Million Dollar Mermaid were stacked together, occasionally two or three at a time so that she would hold her breath for increasingly longer intervals. During one of these stacked sequences, Williams discovered what divers refer to as ‘the rapture’ – a sudden compression of the lung tissue that does not allow for more air to enter its passage ways.Filming Esther through one of the many underwater portholes in the saucer pool, director Mervyn LeRoy and his staff were unaware that Williams was, in effect, drowning before their very eyes until she lifelessly sank out of camera range to the bottom. Reportedly, even then LeRoy was unconvinced as to what was actually taking place. “Esther…what the hell are you doing? We can’t keep you in focus at the bottom of the pool. We’re not lit for that!”

On her next project, Texas Carnival (1952) Esther again encountered a near fatal calamity during the filming of a dream sequence. In it, Esther is seen as the blithe

spirit of co-star Howard Keel’s daydreams, effortlessly floating in and out of his bedroom in a white negligee. To achieve the effect, two identical bedroom sets were built – one on dry land, where Howard Keel pretended to take his nap; the other inside a blackened pool with a roof to sufficiently keep out excess light. Unfortunately, the designers of this set left no space between its ceiling and the water line. The only means of escape for air was through a single trap door that also had been painted black, making it virtually impossible to locate underwater. “I don’t think you know the meaning of panic,” Williams later mused, “…until you’re out of air and can’t see any way out.”

spirit of co-star Howard Keel’s daydreams, effortlessly floating in and out of his bedroom in a white negligee. To achieve the effect, two identical bedroom sets were built – one on dry land, where Howard Keel pretended to take his nap; the other inside a blackened pool with a roof to sufficiently keep out excess light. Unfortunately, the designers of this set left no space between its ceiling and the water line. The only means of escape for air was through a single trap door that also had been painted black, making it virtually impossible to locate underwater. “I don’t think you know the meaning of panic,” Williams later mused, “…until you’re out of air and can’t see any way out.”Though she was still a top box office

draw and would continue to make aquacade movies well into the mid-1950s, Million Dollar Mermaid was the final unqualified success in Esther’s crown. By 1953’s Easy to Love, changing audience tastes, dwindling box office receipts from musicals in general, the end of the star system, and, the infusion of television culture had all conspired to undermine her reputation as a saleable commodity.

draw and would continue to make aquacade movies well into the mid-1950s, Million Dollar Mermaid was the final unqualified success in Esther’s crown. By 1953’s Easy to Love, changing audience tastes, dwindling box office receipts from musicals in general, the end of the star system, and, the infusion of television culture had all conspired to undermine her reputation as a saleable commodity.MGM thrust her into Jupiter’s Darling (1955) an abysmally miscast retread of the lover’s triangle between Fabius (George Sanders), defender of Rome, his lover Amytis

(Williams) and the venomous conqueror, Hannibal (Howard Keel). Opposed to the project from the start, Esther’s rift with L.B. Mayer’s replacement, Dore Schary reached a critical junction shortly before filming began. “He (Schary) was very smooth, almost snide and very condescending, but in one way we were equal. I didn’t respect the pictures he made (and he knew it) and he didn’t respect the pictures I made (and I knew it).” The film’s critical and financial misfire effectively ended the studio’s cycle of ‘everybody into the pool’ decadence that had made Esther Williams an overnight sensation a mere decade earlier.

(Williams) and the venomous conqueror, Hannibal (Howard Keel). Opposed to the project from the start, Esther’s rift with L.B. Mayer’s replacement, Dore Schary reached a critical junction shortly before filming began. “He (Schary) was very smooth, almost snide and very condescending, but in one way we were equal. I didn’t respect the pictures he made (and he knew it) and he didn’t respect the pictures I made (and I knew it).” The film’s critical and financial misfire effectively ended the studio’s cycle of ‘everybody into the pool’ decadence that had made Esther Williams an overnight sensation a mere decade earlier.Although she attempted – and for the most part succeeded in fabricating a legitimate camera persona as a serious actress in 1956’s The Unguarded Mom

ent – an unremarkable ‘who done it’, and 1958’s maudlin melodrama, Raw Wind in Eden, tepid box office response to both projects effectively killed off the remainder of her options and MGM unceremoniously dropped her contract. Worse, mismanagement of her estate by second husband Ben Gage had left Esther in a financial debacle. She owed money everywhere, but chiefly to the IRS. Undaunted, Esther effectively retired from movies to be Mrs. Fernando Lamas on New Years Eve, 1969.

ent – an unremarkable ‘who done it’, and 1958’s maudlin melodrama, Raw Wind in Eden, tepid box office response to both projects effectively killed off the remainder of her options and MGM unceremoniously dropped her contract. Worse, mismanagement of her estate by second husband Ben Gage had left Esther in a financial debacle. She owed money everywhere, but chiefly to the IRS. Undaunted, Esther effectively retired from movies to be Mrs. Fernando Lamas on New Years Eve, 1969.“It’s a lonely business…this stardom,

because you never really feel that it’s safe to confide in anyone. Husbands don’t want to know, even if they’re not the source of the problem. Friends cant’ keep secrets. Even therapists were known to go to the press. You learned not to trust anyone with your confidences and risk busting that pretty pink bubble the studio had constructed around you and your outwardly perfect personal life. The public desperately wanted to believe that you lived a fairy tale…a projection of all their romantic fantasies, so much so that despite everything, you tried to believe it yourself.”

because you never really feel that it’s safe to confide in anyone. Husbands don’t want to know, even if they’re not the source of the problem. Friends cant’ keep secrets. Even therapists were known to go to the press. You learned not to trust anyone with your confidences and risk busting that pretty pink bubble the studio had constructed around you and your outwardly perfect personal life. The public desperately wanted to believe that you lived a fairy tale…a projection of all their romantic fantasies, so much so that despite everything, you tried to believe it yourself.”However, Esther proved

that she had a head for enterprise. She indulged in lucrative department store modeling and attached her name to a line of above-ground swimming pools. She also developed her own line of swimwear. At product launches, openings and benefits she was easily a star attraction.

that she had a head for enterprise. She indulged in lucrative department store modeling and attached her name to a line of above-ground swimming pools. She also developed her own line of swimwear. At product launches, openings and benefits she was easily a star attraction.“When I go to business conventions for my products, it sometimes takes me over four hours to sign all the autographs and pose for pictures. Everyone wants a photo for their store, and I never turn anyone down, no matter how long it takes.”

Despite her considerable success, Esther’s bitter

divorce from MGM festered for sometime afterwards. When the studio released its compendium tribute to the great MGM musicals of the past - That’s Entertainment! (1974), in which sequences from many of Williams’ films figured prominently, Esther sued the studio for their unauthorized use. By 1994, that rift had healed to the extent where Esther agreed to narrate one of the sequences for That’s Entertainment Part 3.

divorce from MGM festered for sometime afterwards. When the studio released its compendium tribute to the great MGM musicals of the past - That’s Entertainment! (1974), in which sequences from many of Williams’ films figured prominently, Esther sued the studio for their unauthorized use. By 1994, that rift had healed to the extent where Esther agreed to narrate one of the sequences for That’s Entertainment Part 3.After Fernando Lamas’ death in 1982, Esther Williams took a very brief hiatus from the limelight. Though she committed to a

Barbara Walters Special and guest appearances on the Dinah Shore Show, perhaps the best snapshot from this later period has Esther entering a local butcher shop, only to be asked the proverbial backstabbing question that befalls most stars in the autumn of their careers – “Didn’t you used to be Esther Williams?”

Barbara Walters Special and guest appearances on the Dinah Shore Show, perhaps the best snapshot from this later period has Esther entering a local butcher shop, only to be asked the proverbial backstabbing question that befalls most stars in the autumn of their careers – “Didn’t you used to be Esther Williams?”“Yes. I used to be” says Esther.

“What the hell happened to you?” the butcher continues, “You’ve gotten older.”

To which Esther replied, “Have you looked in the mirror lately? You’ve gotten older too!”

In her autobiography, Esther would conclude, “What the public expects and what is healthy for an individual are two very different things…I always took it for granted that there would be a life after Hollywood.”

And so there has. Frank funny and as vital as ever, Esther Williams has

endured the waning years of stardom as a top attraction on the interview, lecture and talk show circuit. Her candid, self-effacing and unpretentious observations about Hollywood’s so called golden age are a unique glimpse into that otherwise mythological paradise. Despite, or perhaps, because of the hardships along the way, Esther Williams in life has emerged as something her on screen persona arguably never was; a truly great lady.

endured the waning years of stardom as a top attraction on the interview, lecture and talk show circuit. Her candid, self-effacing and unpretentious observations about Hollywood’s so called golden age are a unique glimpse into that otherwise mythological paradise. Despite, or perhaps, because of the hardships along the way, Esther Williams in life has emerged as something her on screen persona arguably never was; a truly great lady.“I think the joy that showed through in my swimming movies comes from my lifelong love of the water. No matter what I was doing, the best I felt all day was when I was swimming. Of course I still swim. Only now I go in when I have the pool to myself.”

@2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment