A Cabinet full of tarnished dirty little secrets

by Nick Zegarac

Garbo never won an Academy Award. Neither did Alfred Hitchcock.

Alan Ladd, Joseph Cotten and Marilyn Monroe were never even nominated.

Difficult to say what turns the crank of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences (AMPAS) – especially these days when such a target rich environment of raw talent is increasingly hard to come by. And who can justify what performance or film is more worthy of the little gold statuette when pitted against another running along side it, particularly when contenders are from a variety of genres. The Oscars are really the old apples to oranges analogy run amuck.

Reflecting ever so lightly on the hypocrisies associated with Oscar, director Peter Bogdanovich commented, “the way I see it, there’s only one place that does it right. Every year in Barcelona they give awards for poetry. The third prize is a silver rose…the second, a gold one. First prize, the one for the best poem of all, is a real rose.”

Bogdanovich was of course drawing a parallel between ‘real or genuine’ art and the ‘real’ rose, as opposed to manufactured business masquerading as art and the copy of a rose. But by its very essence, film is a copy without any original. It is shadow and light, a flickering spirit that suddenly appears with the dimming of the house lights that evaporates just as quickly after the final fade out. Contemporary talent is like that too. It’s disposable. The days of a Joan Crawford, chewing up the scenery for nearly five decades are decidedly over. And what is made in terms of film output for public consumption now is not so much film art but film product; a slick packaged bit of temporary diversion – often, not well-crafted.

But, back to Oscar, dear Oscar…Oscar Dearest. From the moment that golden boy appeared on the scene in 1927 he became a cultural relic of controversy for the idle idols in movie-land. In those early years the awards ceremony was a private affair, just a simple (at least by Hollywood’s standards) gathering either at the Ambassador Hotel or Cocoanut Grove, put on by the men and women in the industry to acknowledge one another for their ‘hard’ work. But by the late 1930s that ‘little’ ceremony had become the all-consuming festival of morbid fascination with fame - achieving and maintaining it through award status - that quickly extending its tenacity beyond the borders of make-believe.

“You know,” Cary Grant mused, “There is something embarrassing about all these wealthy people publicly congratulating each other.”

He was being polite. But mystery author, Raymond Chandler, whose books had successfully been translated into popcorn sellers, hit closer to the truth. “If you can go past those awful idiot faces on the bleachers outside the theater without a sense of the collapse of human intelligence; and…see half the police force…gathered to protect the golden ones from the mob…and still feel like the picture business is worth the attention of one single intelligent artistic mind, then in the picture business you certainly belong because this sort of vulgarity…from which the Oscars are made, is the inevitable price Hollywood exacts from each of its serfs.”

Yet how many people today recognize what the Academy is really all about. In truth, AMPAS began its life as a sort of ‘guild-busting company union’ – a private organization funded mostly by MGM’s vast resources and primarily designed to maintain control over its artists (or rather, keep them under the proverbial thumb of studios by maintaining a level of disproportionate productivity from its stars. Consider, that the average star personage in Hollywood during the 30s made no less than three movies a year, and, was expected to fulfill obligations on a coast to coast itinerary involving press promotions, public and radio appearances.

Rarely did stars choose these venues or, for that matter, the contents of the films they appeared in. Rather, they were assigned and moved about the lucrative game board of fame and residual returns by their mogul bosses like chess pieces, without any control over how their careers were handled. If any star protested the restraints, well…there was always AMPAS to suggest who should win and who should be excluded from Hollywood’s most coveted award’s ceremony. The less likely you were to receive a nomination, the less popular you became in the eyes of your adoring fans; the less popular, the less lucrative for the studio; the least lucrative resulting in a complete cancellation of one’s contract. Hence, stardom was predicated on a star’s compliance with a smile.

Even Academy-sanctioned columnist Murray Ross was hard pressed to maintain the façade for AMPAS as a benevolent awards provider, stating in print, “The Academy was obviously never meant to be a thoroughly democratic organization.”

And democratic it never has been. By the end of the 30s AMPAS was on the verge of collapse, thanks to the shortsightedness of studio moguls – who had lost the race against union guilds and therefore viewed their association with AMPAS dissolvable; their financial investment in it - pointless. By 1952, as an organization free of studio intervention – and badly needed studio funds - AMPAS was struggling to maintain its yearly honors.

But then came television; for a hundred thousand dollars NBC adopted Oscar as its yearly mascot and from that point on the awards became the property of the studio’s arch nemesis. Audiences stayed home in droves to see the yearly cavalcade of stars like Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Elizabeth Taylor and Ingrid Bergman for free in the comfort of their living rooms. It’s not a pretty piece in Oscar’s ‘all that glitters’ history, but it is history nevertheless.

However, all this backstage intrigue paled to the horse race in front of the cameras. “I’m sure that Mary (Pickford) watched Janet (Gaynor) mount the podium and thought ‘Gee, that would be fun, I’ll have to get one’” TCM host Robert Osborne speculated while still a columnist for The Hollywood Reporter, “That’s all it took. And soon the competition was cutthroat.”

In the old days, Oscar voting was entirely a matter of studio support. Moguls decided which films and stars they would ‘push’ for the Oscar race, and which they would quietly shuffle to the back of their deck – regardless of the innate value in their performance.

Bette Davis figures prominently in an early Oscar scandal. When Davis proved, on loan out to RKO, that her performance in Of Human Bondage was statuette worthy pulp, her alma mater, Warner Bros. quietly refused to back her with votes. The edict on high had a trickle down effect to every star and contract player working at the studio. Nearly three times the size of RKO’s voting roster, the ousting of Davis from even a ‘nomination’ consideration was complete – despite the artistry infused into her craft. “My bosses certainly didn’t help by sending instructions to all their personnel to vote for somebody else,” Davis would bitterly exclaim decades later.

Yet, perhaps Hollywood itself was unprepared for the shifting balance of power; one that saw audience popularity gradually shift from its mature stars to the boy’s club seated in their director’s chairs. You see, the talent both in front of and behind the camera had grown younger throughout the late sixties and early seventies while AMPAS’s voting roster primarily remained the same; comprised of warhorses from the studio’s golden age. This is primarily why the overwhelming infusion of teen and twenty-something talent that set box office cash registers ringing in the early eighties (Molly Ringwald, Eric Stolz, Emilio Estevez, Ally Sheedy, Michael J. Fox, Rob Lowe, Sean Penn, et al) were completely overlooked by their own studios when it came time to mount serious campaigns for awards contenders.

“To tell you the truth it burns my guts,” director Henry Hathaway explained in an interview, “A director is like a painter. In a painting it’s the skill and workmanship that stands out – not the painter…a director belongs behind the camera.”

His remarks were indirect references for Steven Spielberg and his meteoric rise in Hollywood. More popular than most of his contemporaries, Spielberg’s work was quietly despised by the alumni voters who unanimously boycotted such stellar efforts as Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T. and even the director’s attempt to outdo the old timers with old time – though decidedly more masterfully crafted entertainment, with The Color Purple.

The latter was a particularly obvious snub. Spielberg failed to earn a Best Director’s nod even as The Color Purple racked up 11 nominations, including Best Picture. Hence, the L.A. Examiner, who had never been fans of Spielberg were forced to expose the oversight in print with “if a movie has eleven nominations, someone has to be responsible!”

None of Spielberg’s early works was considered beyond the nomination stage – a telling sign that Oscar remained a closed party for a very select controlling interest. In restrained reflection on his losses then, Spielberg confided, “There’s always a backlash against anything that makes more than $50 million…and history is always more weighty than popcorn.” That was Spielberg’s polite way of saying that he understood why the lugubrious epic, Gandhi beat out E.T. for the Best Picture of that year.

In recent years the Academy has attempted to refurbish their tarnished image in much the same way Hollywood and the city of Los Angeles have made strides to renovate their crumbling façade with a new coat of paint so that it more readily reflects the town built on make-believe, not winos and rent-by-the-hour love affairs that overtook its streets and alleys in the late 60s and 70s.

Oscar itself has returned to the ‘glory days’ of glamour that once made the ceremony seem more sedately supreme and regally opulent than any of the underpinning goings-on ever were. After the scant and minimalist downplaying of the 1980s, when most celebrities eschewed limousines for carpools and ignored their fans by descending unannounced into the cement bowels of a parking garage beneath the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, the red carpet has once again been laid downtown, this time in front of the lavish Kodak Theatre.

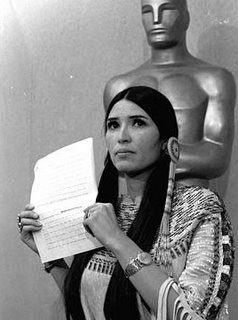

Excitement too has made its comeback into the proceedings - even if it is cut from the same cloth of ‘mindless vulgarity’ that Raymond Chandler would have preferred remained forgotten and buried. And while the quality of film product (for it can hardly be considered more the art than the commodity these days) remains debatable, one thing is for certain – the hard sell and rigorous campaigning of studio PR can still put over the most iconoclastic bit of self-indulgent tripe as award-worthy. But I still prefer the days when all the rhetoric and politics of the likes of a Sacheen Littlefeather were played in the open for the generated shock value and muckraker’s embarrassment it personified. At least then the tone of dissension was both palpable and obvious. Today, who knows what’s going on behind that velvet curtain?

Pearls of Wisdom from the Oscar Closet

“For my second and third pictures I won Academy Awards. Nothing worse could have happened to me.” – Luise Rainer

“It’s really important to remember that we make films for artistic reasons and not to win a little gold statuette.” – Martin Scorsese

“Acting in films is not a goddamn horse race and that’s what makes the Academy Awards so very wrong!” – Richard Burton

“To hell with it! They didn’t nominate me so fuck it. Let’s have fun.” – Cher

“The real show is backstage and out there in the audience. It’s written on the faces of the losers, in the hearts of the winners and told in whispers behind perfumed hands.” – Dorothy Kilgallen

“The Oscar was a marvelous concept. It was supposed to make our business more dignified. But it quickly became just another monetary spectacle.” – Joan Fontaine

“It encourages the public to think that the award is more important to the actor than the work for which he was nominated.” – George C. Scott

@2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment