by Nick Zegarac

"An audience is never wrong. An individual member of it may be an imbecile, but a thousand imbeciles together in the dark—that is critical genius!"

- Billy Wilder

In retrospect, Billy Wilder’s 1950 film masterpiece, Sunset Boulevard serves as a bridge for audiences’ interpretation of that mythical Mecca in motion pictures; between those heady glamour days of golden Hollywood and the corrupt cynical shell of its current incarnation. To some extent, the film capital of the world has always been a flamboyant repository for forgotten daydreams and refurbished nightmares.

The very nature of the business of making movies is firmly predicated on generating a perpetual popularity contest through the perennial exploitation of people. Stars are worth money because they attract an audience. However, when the prevailing wind of fickle adoration shifts, stars become has-beens overnight, or – as the character of Joe Gillis (William Holden) in Sunset Boulevard refers to them – “the waxworks.”

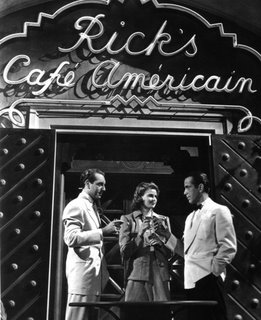

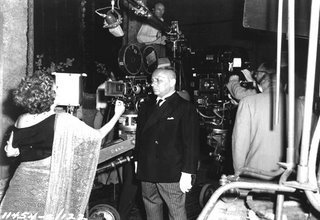

Apart from its importance as a work of art then, Sunset Boulevard is a film generously peppered in Hollywood folklore and verisimilitude. From its cameo performances by forgotten silent stars, H.B. Warner, Anna Q. Nilsson and Buster Keaton, to its almost unobtrusive insertion of directorial giant Cecil B. DeMille (playing himself, and actually on the set of his own production of Samson and Delilah) as Norma’s Janus-faced confident, the film abounds in bittersweet reflections made all the more relevant with each passing year. DeMille (right) was not particularly keen on lending his participation.

In fact, he only agreed to be in the film for $10,000 and a new Cadillac – a fee doubled to $20,000 after Wilder asked DeMille for a close up. “I have ten commandments too” Wilder would later muse, “The first nine are, thou shalt not bore. The tenth is, thou shalt have right of final cut.”

DeMille did, however, lend his own air of authenticity to his brief appearance. Upon meeting Norma Desmond at the door of Stage 18 he greets the actress with “Hello, young fella” – a term of endearment DeMille used often with Gloria Swanson during her heady days on the Paramount backlot.

Though much of the story is executed on carefully constructed sets inside Paramount soundstages, Billy Wilder effective use of several key locations throughout Hollywood - including the famed Schwab’s Drug Store – firmly establish the tale as ‘a story about Hollywood’.

Even the Isotta-Fraschini antique car that doubles as Norma’s limousine comes with an interesting back story. The car had once belonged to socialite Peggy Hopkins Joyce; a present from lover, automobile magnate Walter Chrysler. At a 1929 cost of $50,000 (worth half a million today) the car was the most expensive luxury automobile made for many years to come. Only six currently exist in the United States, including the one used in the film (on display in Las Vegas). In Sunset Boulevard, Wilder’s screenplay makes reference to the fact that the automobile is desired for ‘some Bing Crosby picture’ – a subtle snub to ‘der Bingle’ who had once crossed Wilder’s path by rewriting some of his dialogue on The Emperor Waltz (1948).

“If you're going to tell people the truth, be funny or they'll kill you.” - Billy Wilder

Through his directorial prowess, his sardonic wit and his use in structure of the classic Hollywood narrative, Billy Wilder’s interpretation of both the town and the industry in which he toiled remains one of the most scathing indictments on that dream-like façade behind which lurks a more decrepit sardonic wonderland.

Reportedly, after pre-screening the film for a group of his contemporaries, Wilder was besot by the full wrath of then MGM President Louie B. Mayer who admonished the director’s hutsba at casting an unflattering light on the industry with “You bastard! How could you do that?!?” Reflecting on the minor confrontation years later, Wilder would muse, “If there’s anything I hate more than being taken seriously, it’s being taken too seriously.”

Indeed, L.B. Mayer

had missed that point. Wilder had no misgivings about presenting his embittered take on the land of make-believe to the world at large. Wilder was, after all, the sole survivor in his family after Adolph Hitler’s ethnic cleansing.

had missed that point. Wilder had no misgivings about presenting his embittered take on the land of make-believe to the world at large. Wilder was, after all, the sole survivor in his family after Adolph Hitler’s ethnic cleansing.He was a hardened refugee imbued with a clairvoyance that, even at an early age, probably precluded his initial thoughts of become a lawyer. Instead, Wilder took up as a reporter for a Viennese tabloid newspaper in Berlin. Employing his quick shot, no holds barred style, Wilder graduated from journalism to script writing at UFA Studios in 1929. If it were not for Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, Wilder might never have emigrated - first to Paris and then the U.S.

Speaking no English upon his arrival in Hollywood, Wilder made a quick study of the language, in part due to his friendship with actor Peter Lorre with whom he shared an apartment. A chance meeting with writer Charles Brackett began a friendship in 1938 that soon blossomed into a lucrative writing partnership responsible for Garbo’s comedic Ninotchka(1939) and Barbara Stanwyck’s electrifying, Ball of Fire (1941). By 1942, Brackett had become a producer and Wilder began directing. Wilder’s first big success as a director was the now classic film noir, Double Indemnity (1943), but it was his Oscar win for The Lost Weekend (1945) that paved the way for Sunset Boulevard – a film that no studio prior to his win had wanted to make.

As originally scripted, Sunset Boulevard was to have opened with a scene shot in the Los Angeles county morgue. The body of screenwriter Joe Gillis (William Holden) is wheeled in on a stretcher and shortly thereafter begins an inner dialogue with the other corpses. The sequence was meant to explain how Joe has come to his untimely end. However, reportedly this intro was quietly laughed off the screen during a sneak preview, forcing Wilder to re-conceive the start of his film with the now famous shot of Joe’s body floating face down in the swimming pool of forgotten has-been, Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson).

As it exists in the film today, the pool sequence proved something of quiet dilemma for Wilder and his technicians to figure out. The pool itself was constructed by the Paramount film crew on the property of an abandon estate built by William Jenkin in 1924 for a then unheard of sum of $250,000. At the time Sunset Boulevard began filming, the home belonged to Jean Getty, the widow of oil tycoon J. Paul Getty. The house and grounds were located – not in the 10000 block of Sunset Blvd. as the film proclaims, but - on the 3800 block of Wilshire where a gas station currently stands.

As no proper

plumbing existed, the pool built by Paramount’s craftsmen was never fully functional. However, Wilder had wanted to show Joe’s body from an underwater perspective. After considerable experimentation, it was discovered that if the water was maintained at forty degrees a mirror could be laid at the bottom of the pool into which Wilder and his crew could photograph the action from top side at the edge with minimal distortion.

plumbing existed, the pool built by Paramount’s craftsmen was never fully functional. However, Wilder had wanted to show Joe’s body from an underwater perspective. After considerable experimentation, it was discovered that if the water was maintained at forty degrees a mirror could be laid at the bottom of the pool into which Wilder and his crew could photograph the action from top side at the edge with minimal distortion.Today, it seems quite impossible to consider anyone but William Holden and Gloria Swanson as the washed up writer and forgotten diva respectively. But at the time pre-production began, Mae West was among the first

offered the role of Norma Desmond. West’s penchant for rewriting her own dialogue precluded Wilder from accepting her in the part. Pola Negri was next considered until Wilder realized her Polish accent was too thick. Even America’s sweetheart of the silent era, Mary Pickford was briefly considered, before an inspired afternoon tea in the garden of director George Cukor provided the ideal choice in casting. It is Cukor who must get credit for recommending Swanson to Wilder, a role that will forever be associated with the actress’s name.

offered the role of Norma Desmond. West’s penchant for rewriting her own dialogue precluded Wilder from accepting her in the part. Pola Negri was next considered until Wilder realized her Polish accent was too thick. Even America’s sweetheart of the silent era, Mary Pickford was briefly considered, before an inspired afternoon tea in the garden of director George Cukor provided the ideal choice in casting. It is Cukor who must get credit for recommending Swanson to Wilder, a role that will forever be associated with the actress’s name.

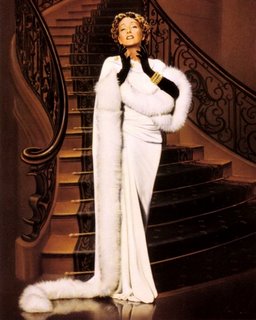

Born in Chicago on March 27, 1897, Gloria May Josephine Svensson had been one of Hollywood’s biggest silent stars. Certainly, she was the highest paid by the mid-1920s. It has been rumored, for example, that Swanson spent a lavish eight million dollars throughout the decade at a time when bread was three cents a loaf. Throughout the early years of the film industry, she appeared in an unprecedented string of mega hits.

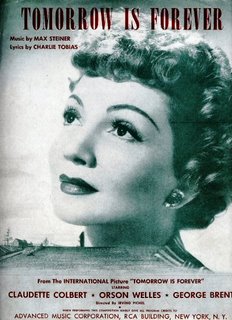

However, Swanson’s penchant for collecting and divorcing husbands, and her not so private affair with Joseph Kennedy (father of future President JFK and Attorney General Robert Kennedy) proved her quiet undoing. After 1929’s disastrous premiere of Queen Kelly (a film that Kennedy financed), Swanson’s popularity in motion pictures severely dipped. Though she made the transition from silent films to sound without much consternation, it was clear that the type of entertainment Swanson had been most closely

associated with had fallen out of fashion.

associated with had fallen out of fashion.By the end of the 1930s, Swanson – like her on camera diva, Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard had become a forgotten relic in Hollywood. However, unlike Norma, Gloria Swanson was far from desperate to make her comeback. During her absence from the screen, Swanson had made a stunning success of both a career on the stage, and, as entrepreneur of a lucrative cosmetic company. Indeed, when she was first contacted by Wilder for the film, Swanson’s assumption was that she had been chosen to play a bit part - not the lead.

By all accounts, William Holden was a far more risqué bit of casting. William Franklin Beedle Jr., the son of a wealthy industrial chemist, who had shot to screen prominence in 1939’s Golden Boy, had since been relegated to playing second string congenial youth bit parts in films that neither advanced nor enhanced his reputation. However, Billy Wilder had been interested in Holden almost from the beginning of planning his film.

Though the part of Joe Gillis had originally been offered to, and accepted by, Montgomery Clift (a choice Clift later regretted and withdrew from just weeks before principle photography began), Holden’s casting in Sunset Boulevard proved the much needed boost in his career. From 1950 onward, Holden’s reputation in Hollywood solidly developed into one of filmdom’s most prominent and readily accessible super stars.

The last bit of inspired casting derived from Billy Wilder’s choice of former director, Eric Von Stroheim to play Norma Desmond’s chauffeur, Max. Indeed, despite his absence behind the camera for nearly thirty years, Stroheim the actor remained a formidable force to be reckoned with on the set. Throughout his life, Eric Von Stroheim had carried that air of self importance and fictional aristocracy that belied his modest physical deportment and impoverished heritage.

Temperamental – at times, to the point of violence, particularly during his zenith in the 1920s, Stroheim had built a name and a reputation for himself within the industry as something of a brilliant ogre. So long as his films made money, his particular brand of boorishness was tolerated by the studio heads. But then there came the two great artistic missteps that dismantled his directorial career; 1924’s Greed (which was extravagant to the

point of absurdity and greatly paired down by the powers that be at MGM) and 1929’s Queen Kelly (for which Gloria Swanson’s admonishment of his manic working style effectively ruined Von Stroheim’s reputation).

point of absurdity and greatly paired down by the powers that be at MGM) and 1929’s Queen Kelly (for which Gloria Swanson’s admonishment of his manic working style effectively ruined Von Stroheim’s reputation). Musing over the folly that had confined him to supporting roles in other director’s movies, Stroheim said, “If you live in France and you have written one good book, or painted one good picture, or directed one outstanding film, fifty years ago, and nothing ever since, you are still recognized as an artist and honored accordingly.

In Hollywood, you're as good as your last picture. If you didn't have one in production in the last three months, you're forgotten, no matter what you have achieved before this. It is that terrific, unfortunately necessary, egotism in the makeup of the people who make the cinema. It is the continuous endeavor for recognition, that continuous struggle for survival and supremacy, among the newcomers, that relegates the old-timers to the ash-can.”

Although the filming of Sunset Boulevard progressed without much incident, one minor debacle did occur on the set while Billy Wilder was busy filming the balcony love scene between Joe and staff reader, Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson).

As Olson later recalled, William Holden’s wife (Artis, nee Brenda Marshall) was on the set during the shoot. Just prior to setting up his first take, Wilder had explained to his two actors that he intended on using their passionate embrace as a dissolve into the next shot, hence the embrace would need to last longer than it actually should in order to cover the span of the match between these two scenes. However, when Olson and Holden locked lips for what seemed an uncomfortable eternity, jealously got the better of Artis Holden who interrupted the shoot by shouting, “Cut! Damn it! Cut!”

Although the world outside of Hollywood embraced Sunset Boulevard upon its premiere, (a swelter of publicity that has since incrementally grown) today, the characterizations in it seem far more poignantly tragic and less grandiose or over-the-top flamboyant than they did in 1950. Norma Desmond is no longer a creature of unique spiraling dementia, but a catch-all for the rabid sad fading façade inherent in all dethroned Hollywood queens.

Indeed, Hollywood accepted Wilder’s masterwork only up to a point. It was, for example, nominated as Best Picture at the Oscars but lost the award to Joseph L. Mankewiecz’s All About Eve – a scath

ing indictment of the New York stage. Hollywood’s awkwardness at self-reflection had, by 1950 been balanced by its overcoming of insecurities decrying the peccadilloes of Broadway – a haughty rebuke that the Great White Way had once reserved exclusively for the film industry.

ing indictment of the New York stage. Hollywood’s awkwardness at self-reflection had, by 1950 been balanced by its overcoming of insecurities decrying the peccadilloes of Broadway – a haughty rebuke that the Great White Way had once reserved exclusively for the film industry.“I never overestimate the audience, nor do I underestimate them. I just have a very rational idea as to who we're dealing with, and that we're not making a picture for Harvard Law School, we're making a picture for middle-class people, the people that you see on the subway, or the people that you see in a restaurant. Just normal people.”

In retrospect, Billy Wilder had the last laugh – for since its premiere, Sunset Boulevard has proven itself to be a genuinely potent snapshot of an era that continues to fascinate – and perhaps exist – behind the closed doors of the studios. Apart from its surface sheen which remains glamorous film making at the height of the studio system, today’s audiences more readily respond to that strange blend of the film’s nasty, heartless and fraudulent undercarriage coated in that elegant shell.

@2006 (all rights reserved).