In an Arthur Freed musical inventiveness and ingenuity had always been hallmarks. Throughout the forties these qualities had been tested and proven fallible on several occasions. On the whole however and as a producer, Freed was the envy of all others – and not just those he worked along side at MGM. To date, Freed’s zeal for musical entertainment coupled with his uncanny ability to spot a talent and make it famous had resulted in a repertory company of trained professionals from Hollywood and the New York stage, collectively functioning as a single unit with one clear artistic vision at its forefront.

Never one to rest on the laurels, Freed marked the beginning of the 1950s by launching into two of his most ambitious projects; An American in Paris and Showboat. For some time, Freed had endeavored to make a musical about an ex-GI pursuing his dream of becoming a painter in Paris. His passion for the project was fueled primarily by the late George Gershwin’s ballet ‘An American in Paris’ and by several other Gershwin tunes penned in collaboration with his brother, Ira.

During preproduction, Freed sent his star Gene Kelly to Paris to screen test Leslie Caron. Already impressed by her work in the Ballet des Champs-Elysees, Kelly discovered a reluctant young girl who had little interest in appearing in films. In fact, Caron would later muse, “I only did it (the test) to please my mother.”

Preproduction began with a singular daunting task for Vincente Minnelli; how to recreate Paris on an MGM backlot. Shooting in Paris was out of the question. With the exception of the film’s opening monologue and one quick glimpse of a limo pulling up to a hotel, all exteriors in the film were pure California confection. Director, producer and star submersed themselves in clippings to aid in the recreation of sets and costumes.

Although preproduction proved a collaborative effort for the most part, it was Arthur Freed who came up with the idea of celebrating the impressionist painters in the final ballet – a decision he never wavered from. Reportedly, Irving Berlin visited the impressionist sets as they were being constructed, inquiring “Am I to understand that you fellas are going to end this picture with a seventeen minute ballet and no dialogue?...I hope you boys know what you’re doing.”

Indeed, there was an intense backlash from MGM’s New York offices upon screening the rough cut of the film prior to the inclusion of the ballet. President Nicholas Schenck thought the budget of $419,664 excessive. Dore Schary, who had succeeded Mayer on the West Coast argued, “…this picture is going to be great because of the ballet – or it’ll be nothing. W

ithout the ballet it’s just a cute and nice musical.” Evidently, the gamble paid off to the tune of $8,005,000 and a Best Picture Academy Award – the first for a musical since MGM’s The Great Ziegfeld (1936). But the highest compliment paid to Freed came four months after An American in Paris went into general release. Impressionist painter Raoul Dufy was visible moved and emphatically impressed.

ithout the ballet it’s just a cute and nice musical.” Evidently, the gamble paid off to the tune of $8,005,000 and a Best Picture Academy Award – the first for a musical since MGM’s The Great Ziegfeld (1936). But the highest compliment paid to Freed came four months after An American in Paris went into general release. Impressionist painter Raoul Dufy was visible moved and emphatically impressed. In the face of such overwhelming critical and financial success, Singin’ In the Rain (1952) passed in and out of the Freed Unit almost as an afterthought – a rich satire of the early sound years in Hollywood immeasurably fleshed out by an extensive Freed/Brown catalogue of 1920s standards. Almost immediately the film was a box office hit, grossing $7,665,000. But its impact ‘as the best musical of all time’ was not immediately evident. Indeed, screenwriters Betty Comden and Adolph Green were shocked during a trip to France several years later when they were accosted with accolades by the noted French film maker Francois Truffaut who was able to quote whole scenes.

On the heels of Singin’ In The Rain there was arguably nowhere to go but down – a direction Freed unwittingly explored with back to back failures; The Belle of New York and Invitation to the Dance. Working under the pressure that times and tastes were changing, and with the very real understanding that MGM’s commitment to musicals had already started to wane, Freed rebounded to profitability with The Band Wagon (1953) a $2,169,120 comedic stab at live theater folk. The film’s overwhelming financial success of $5,655,505 was by now far more important to the corporate front offices than its artistic merit – though The Band Wagon is perhaps the second to last time any Freed musical would so idyllically blend artistry with commerce.

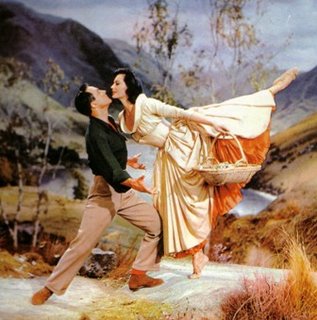

By the mid-1950s, technological innovations, some gimmicky and short-lived, dominated the concerns of most movie studios, including the newly christened widescreen process of Cinemascope. Beginning with Brigadoon (1954) all of Arthur Freed’s subsequent musicals were shot in this 2:35.1 aspect ratio – a framing and composition device that particularly frustrated director Vincente Minnelli. Freed flew to France to discuss exterior locations on Brigadoon with Gene Kelly.

Originally the idea had been to shoot all of the exteriors in Scotland. Freed pursued Moira Shearer – the green eyed ballerina who had made a stunning debut in Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (1948) as well as the Sadler’s Wells Ballet Company for his ensemble. All of his requests were met with polite regrets. However, the biggest regret of all for Brigadoon – a primarily outdoorsy and rustic folktale - was that it would eventually be shot entirely indoors on soundstages at MGM – the first victim of the studio’s cost-cutting measures.

To recreate Scotland in Hollywood, the studio’s art department built a cyclorama that stretched 600 ft. wide by 60 ft. high; a relatively convincing backdrop that Minnelli was never entirely satisfied with. In the final analysis, the studio’s shortsightedness dampened Brigadoon’s reception. At a cost of $2,352,625 Brigadoon proved only a modest success with a return of $3,385,000.

So too did MGM’s frugality hamper Freed’s next two musical endeavors; It’s Always Fair Weather and Kismet (both in 1955). Conceived as a follow-up to On The Town (1949) (which, despite Freed’s meddling, had nevertheless been a colossal hit), the only returning cast member in It’s Always Fair Weather was Gene Kelly – this time cast as a downtrodden ex-GI turned gambler/racketeer. In place of Jules Munshin and Frank Sinatra, Freed settled on choreographer Michael Kidd and Dan Dailey. The film would be the final project co-directed by Kelly and Stanley Donen and the least successful of any, barely breaking even at a gross of $2,485,000. At this point in their respective careers both men were eager for independence from their partnership. As Donen would later state, “I didn’t really want to codirect…we didn’t get on…and, for that matter, Gene didn’t get on well with anybody.”

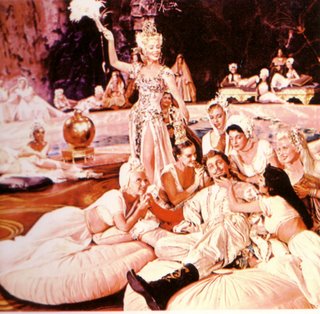

On Kismet, Arthur Freed faced a litany of problems, beginning with Vincente Minnelli’s indifference toward the assignment. Minnelli desperately wanted to direct his pet project, Lust For Life (1956). That provision granted, Minnelli was enslaved to direct Kismet first – a prerequisite he thereafter regretted. As with the limitations imposed on Brigadoon, Kismet was shot entirely on soundstages, but this time without Minnelli’s usual thoughtfulness in staging. Barely breaking even with its $2,920,000 gross, the film was neither an artistic triumph nor the financial powerhouse that both Freed and the studio had hoped for.

If all of these setbacks disheartened Freed’s association with the ever declining lion’s share of his autonomy that had once seemed impervious and untouchable, Freed at least rounded out the decade with two of his most glorious and enduring offerings; Silk Stockings (1957) and Gigi (1958). The former was a musical remake of Garbo’s Ninotchka – a scathing satire brought marvelously in line with 1950s sensibilities. At a cost of $1,853,463.21 Silk Stockings had one of the tightest budgets of all Freed musicals. Its $4,417,753 gross helped ease the pain somewhat. Gigi, however, proved to be the magical elixir capable of wiping clean any and all failures that had gone before it.

Thinly disguised to capitalize on the success of Lerner and Loewe’s Broadway smash ‘My Fair Lady’ – Freed’s Gigi derived its narrative from Colette’s novella about a waif tutored in the ways of a courtesan by her aunt and grandmother. Vincente Minnelli’s excitement for the project extended primarily from his understanding that Gigi would be shot entirely in France – a promise that MGM reneged on during the final months, forcing Minnelli to stage one of the film’s best loved songs, ‘I Remember It Well’ against an obvious backdrop on a soundstage.

This shortcoming excused – Minnelli very quickly discovered the reason why most of his contemporaries abhorred location shooting. Working in France during the hottest summer on record in recent history, many of the corseted extras became ill and fainted. Plastic foliage that had been added to augment several sequences melted in the hot sun. The ice at the Palaise du Glace suffered similar consequences. Yet, despite these setbacks, Gigi proved a critical and box office success – by far the biggest of Arthur Freed’s career, winning nine Oscars (including Best Picture) and earning a then record $13,208,725.

What followed in the career of Arthur Freed after this penultimate moment in 1958 bears little mentioning. For although he still had three films left to produce before retiring (The Subterraneans, Bells Are Ringing, and, A Light In The Piazza) his supremacy as a producer had been severed prematurely by the demise of the studio system. The great advantage during most of Freed’s career had always been that he was assured any and all of the assets and resources necessary and required to make whatever flight of fancy his heart desired.

Even though Freed had never been one to limit himself to only those resources (pooling talent from around the world and forever augmenting MGM’s roster of accomplished performers and artisans), these last attempts at rekindling his former greatness paled considerably in that illustrious tenure. So too was MGM’s ever changing management during those final years a chronic source of aggravation for the aged producer.

For example; when Freed begged then MGM head Joseph Vogel to purchase the rights to the stage versions of Camelot and Paint Your Wagon he was emphatically turned down. A revolving interest Freed had to produce a film based on a cavalcade of Irving Berlin standards, entitled Say It With Music was repeated stalemated until Freed at last was too old and too tired to resurrect the project from its inevitable oblivion. After 42 movies, Freed was ostensibly exhausted of having to explain and defend his every

move to men who were neither loyal to his vision nor understood anything about film making except their bottom line.

move to men who were neither loyal to his vision nor understood anything about film making except their bottom line. Arthur Freed officially retired from MGM in December, 1970. He died suddenly three years later. One of the last awards he received before decamping offices in the Thalberg Building was the International Union of Film Critics Gold Medal. Quite simply, the inscription read “To honor Arthur Freed, Master Musical Maker.” For Arthur Freed, the final flower in that ancient crown he wore so prominently for nearly forty years would always remain Gigi. His legacy in film musicals however, remains unsurpassed.

@Nick Zegarac 2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment