Tuning into the prophecies of ‘Network’

Tuning into the prophecies of ‘Network’by Nick Zegarac

“How do you preserve yourself in a world in which life doesn’t really mean much anymore?”

– Paddy Chayefsky

There is a moment in The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1956) in which harried father, Tom Rath (Gregory Peck) returns home from a stressful day, desiring nothing more than the welcomed embrace of his children only to discover them sprawled in intellectual and emotional paralysis in front of the television and quite oblivious to his presence. Fast forward to a moment from The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1982) in which muckraking watchdog reporter, Melvin P. Thorpe (Dom DeLuise) explains to Sheriff Dodd (Burt Reynolds), “The power of television scares me. I can get the mayor’s own children to throw rocks at him.” What these two filmic moments have in common is an articulation of the influence that television has had on shaping – or perhaps warping - young minds.

The imposed authority that television has assumed in the dehumanization of our emotional responses is at the crux of screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky’s Network (1976) a brutal satire with more than an ounce of truth emerging from behind its tagline; ‘television will never be the same’ and the catch phrase, “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore.” These slogans have since become the calling cards to a younger generation’s rediscovery of the film.

While Network continues to have its share of critical backlash and polite dismissals, primarily from central figures in the news industry – who claim with a half smile that Chayefsky’s premise and perspective are quaintly fraudulent – there is no denying that as a cultural artifact of the last century, television has indeed reshaped our collective mindset through a very skewed and limited perspective. The distinction between what is true and what has been vaguely reconceived and re-imagined for the purposes of entertainment, and a fifty share in the Nielsen ratings, has been deliberately blurred.

Removed by at least one hundred years from television’s conception to cultural leviathan, long since our god-like and insular mandarin for modern times, it now seems not only difficult but perhaps impossible to ascribe any critical responsibility to television for the state of our own collective brainwashing. Whether one chooses the inauguration of de Forest’s audion vacuum tube in 1906, Campbell Swinton and Boris Rosing’s introduction of the cathode ray the following year, or 1939’s first experimental broadcast at New York’s World’s Fair, the introduction of television has done the exact opposite of what it was originally intended to do; provide a window into the realities of our modern world. Instead, television has managed to shape a fiction that has readily been substituted in place of that window as the truth.

It is, for example, a telling bit of historical retrospect to reconsider that the first experimental broadcast in the new medium of television was Franklin Roosevelt’s presidential speech; a prelude to the pop culture, mass marketing of every presidential nominee since who has been forced to profess sincerity over an insincere invention. For television has since adopted the illusion of the Janus-faced hypocrite; the political machine’s greatest ally and worse nightmare.

Despite its persistent illusion as the mere ‘provider/demonstrator’ – a sort of truth machine that nightly invades our living rooms – what television has become (and arguably, always was) is a creator, manipulator and vast distiller of portioned truth into sound bytes that skew the actualities of the moments captured. Over the course of roughly the last forty years, all modern history has been played out as public spectacle on the nightly news; a history largely regarded by most as fact instead of ‘the world according to T.V.’ - not the world as it actually is.

So long as there remained a counterbalance to broadcasting through varied, if biased, accounts of these same events reevaluated from different perspectives on radio and in newspapers across the country, this total saturation in media coverage from television alone was kept at bay.

However, by the late 1950s television had become the dominant purveyor of mass entertainment in the United States. The 1950s, that had began in earnest with an explosion in sales of B&W monitors exclusively marketed to private homes, had provided the major gestalt to shatter the monopoly motion pictures had previously occupied since the late 1920s. Yet, in that great shift there existed the seeds of a damaging effect on our culture’s perception of what the term ‘news’ actually meant. The distinction between ‘newsworthy’ and ‘saleable entertainment’ had already begun to blur.

“I don’t believe a word I hear (from television) as a value, as an esthetic, as a truth” – Paddy Chayefsky.

The problem, it seems, is that for most of our current generation – weaned on news-based entertainment shows like Hard Copy and A Current Affair – the line between fact and fiction has been removed. With its modus operandi derived from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962); “when the legend becomes fact, print the legend” television has assumed a great immodest mantel of purporting to be an ‘information technology’ - but without any responsibility for having to deliver the whole truth and nothing but.

“If you pay attention to television this is a country of hookers, hit men and pimps because that’s the only drama we see on television.”

– Paddy Chayefsky.

If ever a film could be considered an oracle, Cheyefsky’s Network is that vessel. The author of this watershed movie was remarkably clairvoyant in his controversial predictions. For example – in 1976 when the film premiered, the three major television networks were all self-owned and operated. By 2006, conglomerates like General Electric, Time-Warner and Viacom had taken over. The film’s spoofs of the Mao Tse-Tung Hour, Sybil the Soothsayer and Miss Mata Hari and her Closet Full of Skeletons, too, have since become the ‘fact-based’ ‘news-orientated’ programming; America’s Most Wanted, The Psychic Friends Network and A Current Affair with their own slant on sensationalism.

The only prophecy from the film unfulfilled on television today is the first network broadcast of a public execution. “Let’s face it,” Paddy Cheyefsky once acknowledged in an interview, “public execution has been the best show in town for many, many year” but “human life is a hell of a lot more important than your lousy dollar!” “That’s the only part of Network that hasn’t happened yet, and that’s on its way,” suggests the film’s director Sidney Lumet, “I think everybody’s got much more information (today), and is much less intelligent.”

“Our obligation in our industry is to entertain people. We fill up their leisure. That’s what we do. If we manage to give them one shred of insight into their other meaningless lives then we’ve achieved what is called artistry…and that’s bonus.” – Paddy Cheyefsky

Paddy Cheyefsky’s early career grew from a brief tenure working in television on the series ‘Danger’ for CBS, so he came to the writing of Network well versed. Acknowledging television’s power “that transcends anything in the world today” Cheyefsky’s overriding concern was how television’s ninety-five percent country-wide saturation was impacting the overall cultural perspective on world events.

If, as Cheyefsky reasoned, violence in motion pictures had reached a level of extreme gruesomeness, then it was merely a proportionate response to the increased bombardment of violent images seen on television that had, in Cheyefsky’s opinion, a much uglier effect, “not because it breeds violence” he explained, “but because it brutalizes the audience” through the homogenization of acceptable complacency. “You no longer feel the pain of the people, the grief of the mourners.”

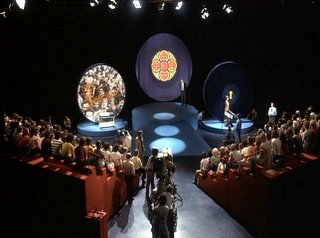

The film, Network is a prophetic glimpse into that morphing from serious journalism into sensationalist propaganda. The film stars Peter Finch as Howard Beale, a man of integrity, honesty and, above all else, corporate professionalism. That is, until he is told he is being sacked by the new corporate management. Faced with the end of his career, Howard announces on air that he is going to commit suicide during his last broadcast; an act of lunacy that gains total press coverage on all affiliates and newspaper headlines the following day. Although the network, headed by corporate whore, Frank Hackett (Robert Duvall) immediately fires Beale, they quickly reinstate him when the Nielsen ratings skyrocket.

Chayefsky’s focus in Network is on the acquisition of independent news agencies by multinational corporations that are only interested in the ratings system and how it equates to fiscal solvency. Corporate entities are perhaps deliberately naïve about the truth as long as it sells more readily and profitably to the public at large as gussied up fiction. “What you see on television is what’s getting money for the network,” Chayefsky explains, “It’s not true,” but rather “…conforming and manipulating popular thought.”

What Chayefsky understood while conceptualizing his ideas into a script, and, what was articulated in his film – that has since proven a prolific projection, is that corporate sponsorship will not and can not tolerate or operate at a loss. Prior to the seventies, networks understood that news divisions were, by their very essence, inherent money losers. As long as the networks functioned as independent media on that assumption, these losses were tolerated within the cannons of American broadcasting.

However, with multinational takeovers, dictated solely by popular demand and timely programming, ‘hard’ news can no longer exist as a fiscal affront to the boundaries preconceived by capitalist productivity or in vacuums unto themselves. To make news popular the content of the news itself had to change; from speeches to sound bytes; hard facts to slickly packaged sensationalism. Multiple anchors, flashy backdrops, ‘human interest’ stories (and most recently, even soap opera previews and cooking and health tips) have become expected and acceptable parts of the daily/nightly news broadcasts in an attempt to make news coverage more exciting, but – as Chayefsky reasoned in 1976 - at what cost?

Notable for its stellar ensemble of acting talent, Network stars William Holden as Max Schumacher, the one voice of dissention in an otherwise profit-driven corporate complex. What the film does exceptionally well is to conceptualize that exploitation of the news from fact-based credibility into foolish spectacle through the slow mental collapse of Howard Beale. Beale is illustrative of the extent to which corporate sponsorship is willing to go to ensure that popularity in ratings outweighs the strict adherence to any academic standard in journalism.

The fate of Max Schumacher in the film is that he is devoured by the same corporate machine he justly accuses of turning Beale into a colossal joke as the “mad angry prophet, denouncing the hypocrisies of our time.” In Schumacher’s case, the joke is on him as sycophantic sexual neurotic and program director Dianne Christiansen (Faye Dunaway) devours his reputation, dismantles his marriage then robs him of his humanity in a perversely wicked parallel to Beale’s ultimate fate. What Paddy Chayefsky has managed to capture on camera is the essence of that blind driving ambition to be the best in an industry that, according the film, clearly has no aspirations left to extol.

“You start off to make a great movie,” Chayefsky once explained, “…settle for a good movie after the first day of shooting…and then (are) just glad to finish it.”

In the final analysis, the end of Network marks the beginning of a period in television broadcasting that has since mirrored Chayefsky’s satire all too accurately in nearly every detail. We are indeed as ‘mad as hell’. But the question remains…are we going to take it anymore?

@ Nick Zegarac 2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment