Frank Capra’s departure from his usual feel good tales of the ‘every man;’ Lost Horizon (1937) was based on James Hilton’s best selling novel; all about British diplomat, Robert Conway – a man of substance who discovers peace on earth in the mythical enclave of Shangri-La. The book read strictly as utopian fantasy. But in the film, Capra managed to interject something of a timeless message for peace that continues to find authenticity in today’s worldly struggles; and something else, a note of sinister darkness emanating from the periphery of that perfect world.

From the benevolently mysterious Chang (H.B. Warner in an Oscar nominated role) to Sam Jaffe’s haunted performance as the High Lama, there remains a sense of doomed folly about this gentle oasis – an ominous precursor leading up to the film’s climactic moment of realization.

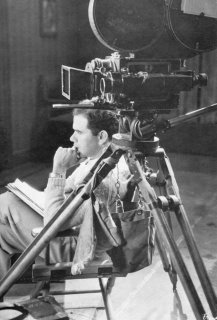

For some time Capra had wanted to make a film based on

Hilton’s novel. However, realizing the considerable budget such a project would demand, Harry Cohn had withstood Capra’s requests for as long as he could. With Cohn’s reluctant complicity, and together with Robert Riskin and Sidney Buchman, Capra began the arduous task of hammering out a screen narrative. The project began in earnest with the complex construction of a ‘flashback’ devise that Capra filmed on March 23, 1936 but later jettisoned from the final cut.

Hilton’s novel. However, realizing the considerable budget such a project would demand, Harry Cohn had withstood Capra’s requests for as long as he could. With Cohn’s reluctant complicity, and together with Robert Riskin and Sidney Buchman, Capra began the arduous task of hammering out a screen narrative. The project began in earnest with the complex construction of a ‘flashback’ devise that Capra filmed on March 23, 1936 but later jettisoned from the final cut.In this flashback, British foreign secretary Robert

Conway (Ronald Colman) is seen aboard the S.S. Manchurian bound for home. Conway is suffering from amnesia until a piano concerto stirs his memory. Impromptu, Conway plays an unpublished Chopin piece. When asked curiously where he learned the music, Conway distantly replies, “Shangri-La” and the story unfolded from there. However, after viewing Capra’s rough cut – over five hours in length – Harry Cohn ordered the story severely cut. To accommodate Cohn, Capra discarded this meticulously conceived preface.

Conway (Ronald Colman) is seen aboard the S.S. Manchurian bound for home. Conway is suffering from amnesia until a piano concerto stirs his memory. Impromptu, Conway plays an unpublished Chopin piece. When asked curiously where he learned the music, Conway distantly replies, “Shangri-La” and the story unfolded from there. However, after viewing Capra’s rough cut – over five hours in length – Harry Cohn ordered the story severely cut. To accommodate Cohn, Capra discarded this meticulously conceived preface.

Instead, the film would open with Conway evacuating the last remnants of white society from the war torn city of Baskul. These unfortunates includes Conway’s brother, George (John Howard), a playful knockabout, Henry Barnard (Thomas Mitchell), a scatterbrained fossil expert, Alexander P. Lovett (Edward Everett Horton) and a fatally stricken prostitute, Gloria Stone (Isabel Jewell).

Capra shot most of this footage in April of 1936 at Van Nuys Airport, leasing a Douglas DC-2 and importing 500 Chinese extras (many of whom could not speak English and therefore could not understand the instructions they were being given) barely v

isible - except in a brief long shot - in the final cut. Together with scenarist Robert Riskin, Capra also added a sequence on location not derived from James Hilton’s novel; the burning of a hanger to light the runway for evacuating planes.

isible - except in a brief long shot - in the final cut. Together with scenarist Robert Riskin, Capra also added a sequence on location not derived from James Hilton’s novel; the burning of a hanger to light the runway for evacuating planes.Escaping on the last plane out of Baskul, Conway and company soon discover that they have been hijacked by a mysterious Oriental pilot (Val Durand) who is flying them deep into the Tibetan mountains. Tragedy strikes as the pilot suffers a fatal heart attack. The plane crash lands on a snowy plain high in the mountains.

What had always been of utmost concern to Capra during his preliminary work on Lost Horizon was how to create not only the look but the feel of extreme cold. His own 1931 story of the South Pole – Daredevil, had incorporated gypsum and marble dust to simulate snow. Although this had been effective in the sequence, no breath showed. For Lost Horizon Capra was determined to remedy this oversight.

He contacted the production manager of California

Consumer’s Corporation and leased one of their refrigerated warehouses for 23 days. Inside this mammoth 13,000 square foot warehouse – refrigerated to a temperature of only 24 degrees, a full size mock up of the plane was reassembled with props and an ice chipper capable of delivering 11 tons of pulverized snow into the air. To add to the scope of these snowy sequences, Capra would later insert legitimate stock shots from Arnold Fanck’s German film, Storm Over Mont Blanc (1930).

Consumer’s Corporation and leased one of their refrigerated warehouses for 23 days. Inside this mammoth 13,000 square foot warehouse – refrigerated to a temperature of only 24 degrees, a full size mock up of the plane was reassembled with props and an ice chipper capable of delivering 11 tons of pulverized snow into the air. To add to the scope of these snowy sequences, Capra would later insert legitimate stock shots from Arnold Fanck’s German film, Storm Over Mont Blanc (1930).His first problem overcome, Capra returned to the narrative with all the escapees survived but stranded in the frozen tundra until an unlikely rescue party headed by a mysterious native, Chang (H.B. Warner) arrives. Chang leads Conway and his party through the frozen wilderness to a hidden paradise deep within the mountain range that is strangely warm, inviting and idealistic in its philosophies on life. There, Conway meets Sondra (Jane Wyatt) and is introduced to Father Pereaux – the High Lama (Sam Jaffe).

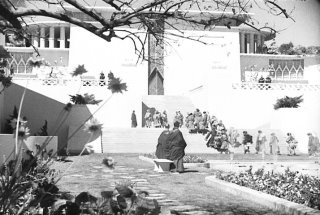

The sheer scope of introduction to Shangri-La as a tangible lost paradise could not be underestimated. Capra employed supervising art director Steven Goosson and art directors Paul Murphy and Lionel Banks on the creation of an idealized structure that met with considerable resistance from purists, because its inspiration drew more from the deco designs of Frank Lloyd Wright than legitimate Tibetan architecture. Nevertheless, the lamasery set constructed at the Columbia Ranch (a property adjacent the studio) was one

of the largest (at 500 feet wide and 1000 feet long, and with a central façade towering 90 feet tall) and most impressive ever built for a movie.

of the largest (at 500 feet wide and 1000 feet long, and with a central façade towering 90 feet tall) and most impressive ever built for a movie.Upon arrival to this magical place, the troupe is skeptical about their hospitable hosts. But then subtle miraculous things begin to happen: Conway discovers inner piece, Gloria’s failing health is slowly restored, Lovett reconnects with his innate abilities as an educator and Henry begins to fall in love with Gloria. Only George is unhappy. He views

Shangri-la as his prison, an interpretation furthered by his chance meeting and growing affections toward a young Russian girl, Maria (Margo) who shares in his quest to escape the controlled serenity and return to her country. To quell George’s suspicions, Conway finagles a meeting with the benevolent ruler of Shangri-La: the High Lama.

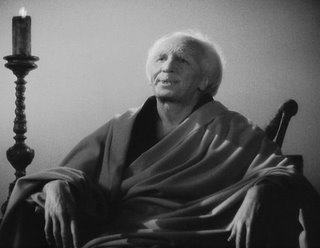

Shangri-la as his prison, an interpretation furthered by his chance meeting and growing affections toward a young Russian girl, Maria (Margo) who shares in his quest to escape the controlled serenity and return to her country. To quell George’s suspicions, Conway finagles a meeting with the benevolent ruler of Shangri-La: the High Lama.Capra had wanted noted character actor, Sam Jaffe for the role. Harry Cohn, however, was not at all convinced of Jaffe’s participation on the project – perhaps largely due to the fact that Jaffe’s political affiliations had loosely branded him a

potential Communist sympathizer. Reluctantly, and at the behest of Cohn’s urgings, Capra hired Walter Connelly for the part and reshot all of the High Lama’s sequences on a newly constructed set.

potential Communist sympathizer. Reluctantly, and at the behest of Cohn’s urgings, Capra hired Walter Connelly for the part and reshot all of the High Lama’s sequences on a newly constructed set.However, when Cohn screened both Jaffe and Connelly’s performances he had to reluctantly concur with Capra that his first choice of Jaffe had been the right one from the start. Even before this minor controversy, gossip columnist Louella Parsons had managed to generate a sensation over the casting of the High Lama with a puff piece that suggested actors A.E. Anson and Henry

Waffle had been set for the role. Both Anson and Waffle died after doing their screen tests – an ominous curse that made Jaffe’s debut all the more dramatic.

Waffle had been set for the role. Both Anson and Waffle died after doing their screen tests – an ominous curse that made Jaffe’s debut all the more dramatic.One aspect of Jaffe’s performance that Cohn absolutely refused to relent on was its length. Capra had literally photographed whole speeches verbatim from Hilton’s original text. In some cases, these speeches ran on for more than twenty minutes at a time – a length both Cohn and the author agreed dramatically slowed down the narrative and damaged the overall impact of the story.

The narrative progressed with George prodding his brother to steal away into the night with him and Maria. Warned earlier that Maria is two hundred years old (even though she looks no more than twenty-one), the prophecy of her fate is fulfilled when, after venturing beyond Shangri-La’s ageless borders, she decomposes into a mummified corpse before Conway and George’s eyes. Realizing that the mysticism and magic of Shangri-la has been legitimate, George succumbs to an act of cowardice, throwing himself off the mountainside and leaving Conway to fend for himself.

Half frozen and starved, Conway is discovered by natives in a small Tibetan village and reunited with his British colleagues in London. But he cannot get either Shangri-la or Sondra out of his mind. Abandoning his duties, Conway drudges back through the snow in search of the peace he left behind.

Although Capra provides both Conway and his audiences with a glimpse of Shangri-la glistening in the distance through the wind-swept Himalayas he never quite rectifies the journey for either. Does Conway get back to Shangri-la? Does he find Sondra awaiting his return? Or has he merely hallucinated paradise lost and is doomed to die alone on the mountainside?

Undoubtedly, Capra’s attention to authenticity was working overtime on this opus magnum. But it was also working against Harry Cohn’s patience. In the end, Capra lost six reels of footage – much of it establishing the burgeoning romances and changes occurring to the temperament of the entire rescue party. As a result, the narrative – even today – tends to suffer from a series of inexplicable gaps that leave a choppy impression behind. Still, Capra had hoped for a success beyond all his previous endeavors.

Unhappy chance, for both director and mogul that Lost Horizon’s three and a half hour preview in Santa Barbara was not what either had expected or hoped for. Disappointed and disillusioned by the lack of immediate response to the film he considered his masterwork, Capra reluctantly distilled his narrative to a mere 132 minutes – functional and compelling, though hardly inclusive of all the effort he had put forth in the preceding months.

Even then, the general release of Lost Horizon failed to recoup its $1,200,000 budget. But the story of Lost Horizon – the film - did not end there. During an unrelated press conference speech several years later, President Franklin Roosevelt made a joking reference to the location of a hidden military base as being located in Shangri-La. Almost instantly a renewed interest sprang up around the film. However, for its 1942 reissue, Harry Cohn took to modifying the film even further, cutting its running time down to 107 minutes and changing its main title to the more awkward Lost Horizon of Shangri-La.

From that moment on, the film as it came to be more widely known and exploited through television reissues and private screenings only existed in the Cohn (not Capra) version. Shelved for years, Lost Horizon’s original camera negative deteriorated to the point of no return and was thrown away – leaving only truncated second and third generation prints available for public viewing.

However, in the mid-1970s preservationist Robert Gitt and UCLA undertook to conduct research into the restoration of Frank Capra’s original 132 minute cut. From varying source material that had been gathered around the world and still photos inserted to compensate for the (as yet) still missing footage, Gitt and his associates managed to cut together a facsimile of what the original film must have played like. Sadly, as a film in totem, Lost Horizon remains a lost film; a tragedy since what exists continues to sparkle with a ghostly brilliance that few Hollywood productions of its vintage attained.

POSTSCRIPT to the career of Frank Capra

Capra’s career never entirely recovered from the financial failure of Lost Horizon. He would continue making films with varying success – most notably, Meet John Doe (1941) and the political drama, State of the Union (1946). But his feature film career was sidetracked with a commitment to co-direct eight military propaganda documentaries between 1942 and 1945. The Why We Fight series earned Capra Oscars, but it put his professional career on hold. His return to features – It’s a Wonderful Life (now, regarded as a quintessential holiday classic) was virtually ignored upon its initial release. Produced under Capra’s independent banner, Liberty Films, its disappointing box office bankrupted his fledgling company.

Capra regressed with like-minded light and fluffy fair that had served him well during his heady successes in the 30s. But more often than not, these subsequent projects; Here Comes The Groom (1951) and, A Hole in the Head (1959) were met with cynical indifference. Capra’s final film, A Pocketful of Miracles (1961) was a remake of his own Lady for A Day (1933) a once poignant programmer turned obnoxious by Bette Davis’ gregarious central performance.

As with all aging eminences of his vintage, Capra gracefully retired from the fray of film making, content to quietly age away of the public spotlight, but still gracious enough to accept whatever projects came his way. He produced several television specials in his later years and even found the time to pen his memoirs in an autobiography; The Name Above The Title.

Ever interested in giving interviews and providing his perspectives to young film makers, Frank Capra remained active until his death of a heart attack at the age of 94 in 1991. The man may be gone, but his legacy on film, that inimitable positivism and belief for a better tomorrow is eternally ingrained in anyone whose thoughts are only half secured in daydream.

@Nick Zegarac 2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment