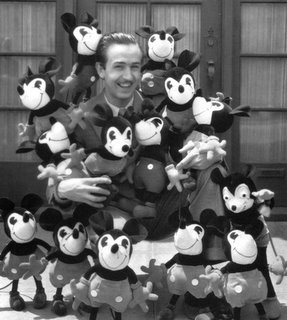

“I hope we never lose sight of one thing; that this was all started by a mouse.” – Walt Disney

He transformed a primitive dumb show into a profoundly visceral art form, and in the process forever altered our collective perceptions of childhood.

During his 43 year tenure in Hollywood, Walter Elias Disney lived to see his name and creations become touchstones in Americana. Pioneer, innovator, and in possession of one of the most fertile imaginations this world has ever known, Walt Disney received more than 950 international honors during his life time; including 48 Academy Awards, 7 Emmys, honorary degrees from Yale, Harvard, the University of Southern California and UCLA; the Presidential Medal of Freedom; France’s Legion of Honor, and Officer d’Academie; Thailand’s Order of the Crown; Brazil’s Order of the Southern Cross; Mexico’s Order of the Aztec Eagle; and the Show of the World Award from the National Association of Theatre Owners.

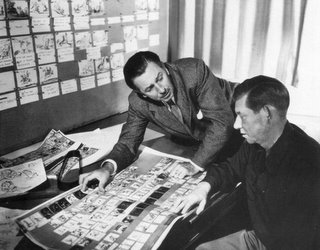

The creator of Mickey Mouse and Disneyland was born in Chicago, IL on Dec. 5, 1901. Raised on a farm near Marceline MI, Walt became interest in drawing at an early age. Beginning his career as an illustrator, then animator of early silent cartoon shorts affectionately titled Laugh-O-Grams, Disney slowly honed his craft. In August of 1923, he moved to Los Angeles, determined to make a go of cartoons as his vocation. Pooling money with his brother Roy, the two embarked on an independent film producing career. Their Alice comedies – which placed a live child in an animated world – were popular but short lived.

However, in 1927 there was a larger crisis looming on the horizon; Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. Walt had segued into the production side of the business. However, in entering into his contract with Charles Mintz to produce the Oswald cartoon series, Disney had inadvertently sold his licenses on the character. Hence, when Mintz decided to liquidate the franchise in favor of cheaper labor at Universal, Disney lost the rights to produce future Oswald cartoons.

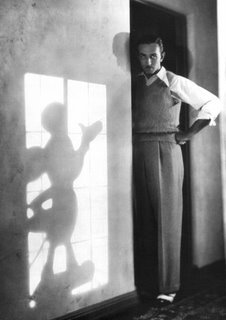

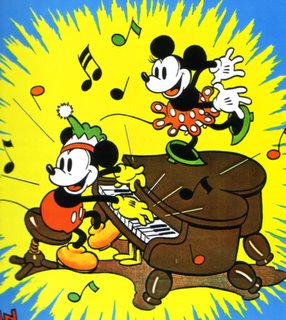

But the debut of Mickey Mouse in Steamboat Willie in 1928 created a minor sensation that, arguably, the world is still recovering from today. Walt supposedly conceived Mickey on the train back to Hollywood. Walt had also managed a minor coup – the signing of Oswald’s chief architect and Mickey’s benefactor – artist, Ub Iwerks. Debuting Mickey Mouse using what was then a very primitive method of recording synchronized sound, the gimmick paid off handsomely. Mickey Mouse became an overnight celebrity, eclipsing Oswald’s popularity and launching the start of Disney animation.

From 1928 on, Walt constantly strove to perfect that art. He established the first exclusive patent with the Technicolor Corporation for his Silly Symphonies series, winning several Oscars including Best Song ‘Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf’ in The Three Little Pigs (1932), and another Oscar for the patented invention and introduction of the multiplane camera in The Old Mill (1937).

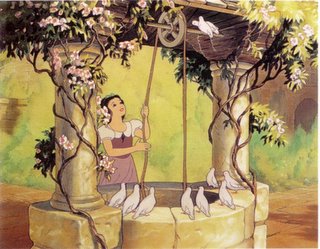

A bit of a maverick in his early years, Walt borrowed against his own life insurance to bring Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1932) to the screen. At a then unheard of cost of $1,499,000.00 the project was affectionate nicknamed ‘Disney’s folly’ – a nearly unanimous appraisal within the industry that seemed to signify its’ being doomed from the start. In point of fact – and legend – Disney was on the cusp of immortality.

Snow White & the Seven Dwarfs was both a critical and financial success; a conscious and seamless exercise in risk-taking and a text book example of economy in film construction flawlessly married with, and complimentary to, its’ extravagance in invention. Walt was honored on Oscar night by a jubilant Shirley Temple, who presented him with a special statuette and seven miniatures (one for each dwarf).

It was just the beginning. An instinctive storyteller, Disney pursued an aggressive campaign to bring culture and beauty to the masses with his next two endeavors, and at a great peril of bankrupting his fledgling studio. Although each project brought great prestige to Disney and the art of animation, neither Pinocchio nor Fantasia (both made in 1940) were financially successful, despite each film sharing in superior craftsmanship and execution to the efforts put forth in Snow White.

Perhaps the best argument for Pinocchio’s failure is that Collodi’s tale of a marionette come to life is populated by despicable characters that do not lend themselves instinctively to the ‘Disney touch’ for cuteness and light. The film is most fondly remembered today for its mature handling of the more subtle aspects of the fairytale, as well as its memorable characterization of Jiminey Cricket (voiced by Cliff Edwards) and the inspirational Oscar-winning song ‘When You Wish Upon A Star.’

With regards to Fantasia’s failure at the box office – in hindsight it seems that Disney did not anticipate the unwillingness of his audience to accept a marriage between Mickey Mouse and conductor Leopold Stokowski. The former was pop culture personified; the latter, one of the most noted, admired and instantly recognized faces in classical music. Originally, Disney had conceived of a one act short in which Mickey would perform an interpretation of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

However, when costs on that short proved prohibitive, Disney expanded his initial concept into something he ultimately labeled the ‘concert feature:’ a repertoire of classical music fleshed out with inspired interpretations drawn by his animators. Indulging his technological side, Disney developed a crude precursor to stereophonic sound (dubbed Fantasound); a process that proved needlessly expensive and grossly cumbersome in its installation.

Although press coverage leading up to Fantasia’s premiere was monumentally positive, subsequent reviews of the film were mixed to poor. For film buffs of the period, Fantasia appeared too high brow, while musicologists found the very idea of putting picture to sound (with concrete, often comedic images no less) a blasphemy of high culture.

Following these financial debacles, Walt’s own ambitions for subsequent features Dumbo (1941) and Bambi (1942) were greatly tempered. Hence, with Bambi, and particularly Dumbo there is a sense that Disney is holding back. This is not to discount either features’ merits – for there are many, and in fact, both movies were well received upon their initial release.

At about this same time, Walt’s commitments were interrupted by assignments to produce documentary ‘propaganda’ cartoons for the United States. Disney also indulged in a bit of goodwill policy with Latin America. In between these ventures (which kept Disney artists busy, but produced only modest profits) Walt startled the industry with his competent foray into live action films with Song of the South (1946). An adaptation of Robert Lewis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1949), as well as a sentimental and nostalgic look at Americana circa 1900; So Dear to My Heart (1949) continued this cycle of unpretentious, solidly crafted films (rarely screened or seen today). At the end of WWII Disney was once again free to pursue his own interests, but his financial resources were at an all time low.

The 1950s were a time of great upheaval in Hollywood in general. The insurgence of television had unilaterally diminished box office revenues for all the major studios. With the ‘if you can’t beat ‘em join ‘em’ philosophy – Disney embraced the new medium, launching several moderate to highly successful weekly series including The Mickey Mouse Club (1950-1960), Zorro (1955-1957), Davey Crockett (1955-1962) and Disneyland (1951-1966); the latter an hour long Sunday night show that Disney used primarily as a means to promote his latest feature films and his pending dream for a theme park.

To reason that all pistons were firing at the Disney Studios throughout the 1950s is an understatement. Walt inaugurated the start of the decade with one of his best fairytale reincarnations - Cinderella (1950) a return to his grand storytelling days of old. Those who had fondly grown up with Snow White eagerly embraced the similar tale of a young maiden’s faith in the future. While the film was greeted with ecstatic reviews and lucrative returns, for Walt at least, this initial success did not entirely breed more of the same.

His subsequent features; Alice in Wonderland (1951) and Peter Pan (1953) are, at best, variations on stories far too detailed for an ‘under two hour’ running time. In pruning each story to a manageable film length, Disney indiscriminately cut whole scenes and entire characters from both works of literature (particularly Lewis Carroll’s Alice, who is missing at least two thirds of her adventures in wonderland in the Disney version). Greeted indifferently by audiences and considerable outrage from well read purists, neither film proved a particularly outstanding example of Disney at its best – though each is entertaining if one sets aside the source material and regards the films on their artistic merits alone.

By 1956 Disney embraced Cinemascope (the newly christened widescreen format) and marked a return to form with the release of Lady & the Tramp – a delightful lighthearted departure from the formulaic fairytales - all about the ensuing romance between a cultured cocker spaniel and devil-may-care mutt.

Walt also launched into a live action version of Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) – originally intended as an animated feature. Of all his subsequent efforts, 20,000 Leagues is the most immaculately conceived and detailed; an inspired entrée for the family-orientated palette and by far the most adult in theme. The overwhelming critical and financial success of 20,000 Leagues was quickly followed by a string of high quality, critically acclaimed literary adaptations including Swiss Family Robinson (1956) and Pollyanna (1963).

Yet, by far Disney’s most monumental achievement of the 1950s (and arguably, his life) was the inauguration on July 17, 1955 of a concept that had been in gestation for at least twenty years; the Disneyland theme park in Anaheim California. A $17 million dollar wonderland dedicated to the children of the world, the concept for Disneyland had derived from Disney’s own boyhood fascination with railroads while growing up in Marceline.

After WWII, Walt’s doctor had suggested he take up a hobby to divert his stress from running the studio. Walt decided on model trains – an affinity shared by one of his animators; Ward Kimball. In no time, the two had built a functioning locomotive in Kimball’s backyard. Fascinated by their achievement, Walt sought to carry over the project into having a rail system installed on the studio lot as a means of transportation.

Gradually, the idea grew to more grandiose proportions. Walt’s background in film making offered a unique departure in the conceptualization of his theme park. Unlike the layout of traditional amusement parks (as unrelated claptraps of attractions and booths haphazardly strung together), Walt’s concept for Disneyland owed much more to the architectural planning of a studio backlot; the only difference being that backlots are two dimensional facades, while the ‘sets’ at Disneyland open onto fully functional attractions and other venues.

While Disney’s creative personnel eagerly embraced the project – as Walt was known for his passionate persuasive manner – his financial accountants saw little initial value in yet another investment for a company whose profits were already stretched thin. Undaunted, Disney engaged ABC television for the purposes of self-promotion. He also secured back loans with the acquisition of shares in ABC-Paramount. These shares diversified and stabilized his bottom line for investors.

The opening of Disneyland was a critical success, especially for those only able to witness the ceremony on television. But behind the scenes it proved a frenetic nightmare, forever after affectionately known around the lot as ‘Black Monday,’ Many of the attractions had not been properly or rigorously tested and developed mechanical difficulties throughout the day. Although only 6,000 invitations had been sent, 28,000 people arrived for the Grand Opening – most holding counterfeit tickets. The last minute rush to prepare the park resulted in workman completing the finishing touches just hours before the ribbon-cutting ceremony. However, a plumber’s strike had prevented the installation of operational water fountains throughout much of the acreage. Women’s high heels sank in the freshly laid asphalt, sizzling in 110 degree Fahrenheit heat.

If all this behind the scenes chaos tested Disney’s limits in tolerance and patience, he showed none of his anxieties during the park’s dedication: “To all who come to this happy place – welcome. Disneyland is your land. Here age relives fond memories of the past…and here youth may savor the challenge and promise of the future. Disneyland is dedicated to the ideals, the dreams and the hard facts that have created America…with the hope that it will be a source of joy and inspiration to all the world.”

Walt could at least carry with him the personal satisfaction that by 1965, a mere ten years after that disastrous opening day, more than 50 million visitors had eagerly passed through Disneyland’s gates making it the number one vacationer’s attraction in the world. As the park slowly evolved under Walt’s tutelage, his film empire continued to produce live action films.

The rather lackluster response to Disney’s most ambitious animated movie to date, Sleeping Beauty (1959) had once again challenged his financial resources – a condition greatly counterbalanced by the popularity of The Parent Trap (1960) and what many consider today to be Walt’s crowning achievement; Mary Poppins (1964).

Walt had made several attempts at wooing Poppins’ author, P.L. Travers. Travers however had zero interest in the project. She was also concerned that Hollywood’s version of beloved books in the past had often veered too far away from the author’s original intentions. Undaunted, Walt proceeded with preproduction – well aware that if Travers did not provide her consent – even after all the money had been spent – he would have to abandon the project.

Enamored with Julie Andrews’ performances on the stage in Camelot and My Fair Lady, Walt gambled her fresh pert and plucky nature against her status as an ‘unknown quantity’ to American film audiences. It was roughly at the time of Mary Poppins’ premiere that Walt’s health began to slowly deteriorate. Undaunted or perhaps acutely aware that time was running out, he gallantly launched into preproduction on The Happiest Millionaire (1967).

However, after a virulent respiratory infection sidelined his involvement on the project, Walt was rushed to the hospital where he was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. Though he had smoked throughout most of his adult life, the diagnosis came as quite a shock – one he kept from all but his closest entourage until the day he died; Christmas Day, 1966.

The Disney legacy has since mutated, or perhaps diverged somewhat from the plans Walt had in development at the time of his death. EPCOT, for example, had initially been planned as a functional city of tomorrow – not another theme park, and there is little to suggest that the current moratorium on traditional animated features would have been embraced by the old master.

What Walt Disney, the man, symbolizes – perhaps more so today, are the high ideals of a folk hero, legend, pop icon and philanthropist. Disney’s popularity was always firmly based in the very best of American traditions. But today, standing in reflection some forty odd years removed from his personal touch, Walt’s creative works continue to inspire the young and young in heart, firing our collective imagination and reminding audiences of a very concrete reality, given life from the heart of the ultimate dreamer.

@ Nick Zegarac 2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment