Busby Berkeley: colossal genius or masochistic joke.

The debate over America’s premiere choreographer from the 1930s rages on, fueled primarily by conflicting testimonials from the people who worked for him and by nearly six decades of fraudulent academic debates (most of them based in Freudian feminism) that have attempted to place Berkeley’s representations of the female form divine somewhere between merely odd to arguably compromised as objectified things rather than glorified women.

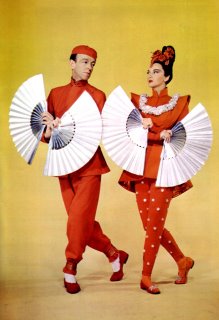

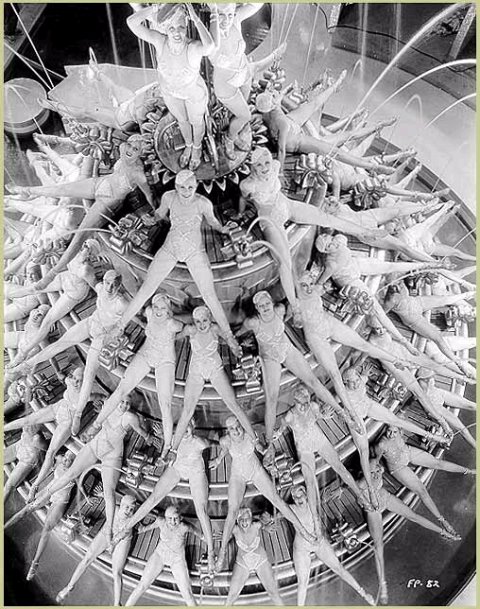

There is no denying that as an artist, Berkeley’s ‘use’ of women is in strict service to his construction of conformity - elaborate human kaleidoscopes: vast and mind-boggling geometric patterns that unfold as if by some great domino effect to produce an endless ‘exploitation’ of arms and legs all preening and kicking in unison. Yet, so too is there much to suggest that as an artist Berkeley was inclined to liberate the chorine from her traditional nameless place amongst the backdrop and props. No more confined to long shots, Berkeley drew the focus of his camera in to showcase bouquets of fresh faces blossoming with girlish pride. “We’ve got all these beautiful girls,” Berkeley used to say, “Why not let the public see them?”

The essential magic that is Busby Berkeley on film exemplifies pure escapism at its most wholesomely playful. In recent years, Berkeley’s influence as a choreographer cannot be underestimated. He has been endlessly reincarnated in everything from the ‘Be Our Guest’ animated sequence in Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, to the Ice-capades and, more recently still, in television commercial endorsements for The Gap and Old Navy. Even today, the American Thesaurus of Slang continues to identify his name with a definition of the scope and fancy in ‘any elaborate dance number.’

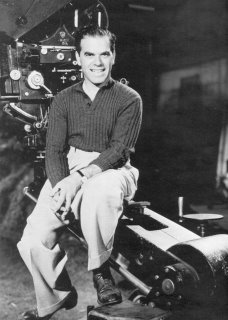

Like so many of the greats of his vintage, William Berkeley Enos was born on November 29, 1895 to struggle, hardship and poverty. He had the very modest advantage of being born close to his future vocation - calling Los Angeles his home. But the death of his father precluded young William from having a normal childhood. Henceforth, the only great loyalty Berkeley would cultivate over the rest of his life was to his mother. In fact, she lived with Berkeley until her death.

In 1918, Berkeley joined the U.S. Army as a lieutenant – a fortuitous decision that ironically paved his way to becoming a choreographer. Fascinated by the precision of military drilling, Berkeley employed much of his early military expertise on his first musical assignment after the army; Broadway’s Holka-Polka. Within a few short years, his enigmatic style had caught the attention of patrons and his contemporaries. Berkeley directed such stage luminaries as Eddie Cantor and worked for no less than Broadway impresario, Florence Ziegfeld Jr. on several of his most popular shows.

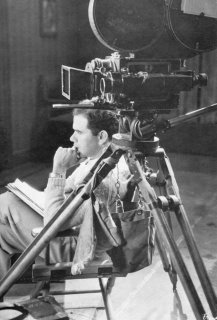

Enjoying the autonomy of the stage immensely, Berkeley expressed initial disinterest in propositions from Hollywood where ‘dance directors’ were merely assigned to train dancers without actually being involved in the execution of the final routine, the positioning of the camera or final edit. Eventually, Berkeley convinced producer Samuel Goldwyn to let him have a go at staging a production number his way. However, time was not on Berkeley’s side – at least for the moment.

By 1931, the Hollywood musical had already run its course. Too many haphazardly staged and expensive flops had all but labeled the genre box office poison – a disheartening turn of events that made Berkeley unemployable. He did not remain so for very long.

Then chief producer over at Warner Brothers, Darryl F. Zanuck bought out Berkeley’s contract with the prospect of having him stage the musical portions of 42nd Street (1933) a film billed as ‘the new deal’ in entertainment. From a purely narrative standpoint there was nothing ‘new’ about the project. A standard melodrama lightly peppered in comedy, the plot of 42nd Street focused on frustrated Broadway producer, Julian Marsh (Warner Baxter) whose career and reputation are on the line. Marsh’s temperamental nature mirrored Berkeley’s own. He was a relentless task master who insisted upon precision and perfectionism – occasional at the point of an insult.

From a technical standpoint, 42nd Street marked the official debut of the Berkeley style on screen. In three grandiose production numbers (all butted up against one another for the film’s finale), Berkeley’s imagination reigned supreme, transforming the relatively stationary vignettes into a revolving mass of surrealistic beauty. In the last of these sequences, Berkeley transforms his small army of chorines into the urban landscape of Manhattan atop which are perched dancers Ruby Keeler and Dick Powell.

The overwhelming response to the film generated two guarantees: first – that Berkeley would be ordered to make more of the same, and second, that audiences had at last discovered a new reason to indulge their whimsy in the Hollywood musical.

Berkeley’s follow up projects at Warner Brothers (Footlight Parade 1933, Wonder Bar, Dames – both in 1934, and the perennially popular Gold Diggers series) were basically 42nd Street revisited in plot, character and overall story structure. Their one note of distinction it seems was Berkeley’s execution of the musical portions which were becoming increasingly intricate. In Footlight Parade, for example, Berkeley staged the sublime ‘By The Waterfall’ – a swimming pool spectacular (predating Esther Williams extravaganzas over at MGM) capped off by a bizarre ‘ejaculating’ fountain/tower populated by swimsuit attired chorines.

In Gold Diggers of 1933, he employs an army of white satin chorines caressing violins in tri-hooped silk skirts and outlined in neon tubing to form one gigantic Stradivarius playing ‘The Shadow Waltz.’ In Dames, (possibly his best work), Berkeley unfolds kaleidoscope upon kaleidoscope of sharply contrasted dancers in white blouses and black tights, whereupon the final master shot is seamlessly frozen to allow for the protrusion of Dick Powell’s face in extreme close up, warbling the final strains of the title song.

But by far, Berkeley’s most universally respected moment in American film is ‘The Lullaby of Broadway’ sequence from Gold Diggers of 1935; a sublime perversity in which tragedy and death spark the most elaborate tap routine ever conceived on film. In both its scope and undertaking ‘Lullaby’ is a marvel of ambitious film making.

Unfortunately for Busby Berkeley, his tenure at Warner Brothers was nearing its end. His perfectionism – greatly admired on the screen, often translated to bouts of cruelty and rage on the set. When he was not busy planning or executing his next number, Berkeley drank, often to excess. Temperamental and frequently frustrated (and arguably, frustrating to work with) by his inability to procure a complete directing assignment, Berkeley’s outspoken criticism eventually garnered the quiet distemper of his bosses. Warner Brothers relented to his request to direct two non-musical projects; but neither was a critical or financial success, sealing Berkeley’s fate at the studio.

In the 1940s, Berkeley grew more embittered with his work, even after moving to MGM where he was hired once again as a choreographer for other director’s projects. To many who worked with him during this period, Berkeley seemed increasingly prone to fits of unprovoked rage and violence. He went through three marriages in short order and was tried for first degree murder after hitting another vehicle while driving drunk. His acquittal of these charges did not exonerate the inner demons that continued to plague him, and after his mother’s death (his one enduring champion) Berkeley attempted suicide.

Professionally speaking, however, Berkeley made his first mark at MGM directing the finale from Broadway Serenade (1939) with Jeanette MacDonald. His talents were next put to use on the Fascinatin’ Rhythm finale in Lady Be Good (1941) – a tour de force that provided resident tap dancer, Eleanor Powell with one of her most memorable and ironically enjoyable filming experiences.

But by far Berkeley’s most challenging collaboration of this period derived from a tempestuous relationship with the teenage Judy Garland whom he choreographed in Strike Up the Band (1940) Babes on Broadway (1941) and portions of Girl Crazy (1943). Berkeley proved so relentlessly tyrannical on this latter assignment that he was fired midway through the project and replaced by Norman Taurog. His one enduring set piece from Girl Crazy – the dude ranch finale set to Gershwin’s ‘I Got Rhythm’ proved an exercise in manic super kitsch. In truth, Judy Garland’s addiction to prescription drugs at this time had made her hypersensitive to criticism for which Berkeley frequently exercised his penchant.

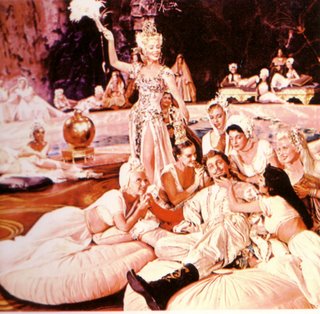

Placed on suspension from MGM, Berkeley went to 20th Century Fox to direct The Gang’s All Here (1943) a glossy, slickly packaged Technicolor musical costarring Alice Faye and the bombastic Carmen Miranda. Once again, however, Berkeley proved to be his own worst enemy. When warned that his camera boom might clip Carmen Miranda, Berkeley ignored the suggestion to re-choreograph his planned camera movement and nearly injured Miranda by sheering off her elaborate headdress. The film, a great success, was nevertheless not worth the effort of tolerating Berkeley behind the scenes – at least, in reference to Fox executives.

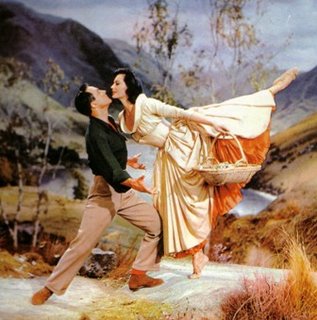

Berkeley returned to MGM, effectively ending his all too brief 40s tenure as a director with Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949), a modestly budgeted musical that passed effortlessly on the screen but failed to recapture the essence of his inimitable style. For his part on the project, star Gene Kelly was used to choreographing his own dance routines and came into constant conflict with Berkeley. Eventually, Kelly’s co-collaborator, Stanley Donen was brought in to finish the project – quietly easing Berkeley from his authority.

Berkeley’s smoke and trapeze sequence for Esther Williams in Million Dollar Mermaid (1952) marked something of a return to form. The following year, Berkeley topped his water ballet with an even more ambitiously mounted water ski sequence for Easy to Love, and an inspired bit of impressionism run amuck with dancer Ann Miller tapping around an orchestra buried (except for its instruments) below floor level in Small Town Girl (1953).

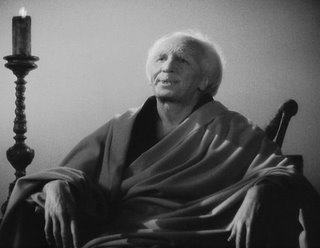

Fate and ill-timing conspired to prematurely oust Berkeley from MGM – a move in keeping with the slow demise of the studio system itself and changing audience tastes that effectively brought down the Hollywood musical as a viable screen art form. Burnt out, discarded and sinking deeper into depression and financial debt after his mother’s death, Berkeley attempted suicide again. He was all but forgotten – returning briefly to MGM a decade later to stage the scant and lack luster dance routines for Billy Rose’s Jumbo (1962); an abysmal Doris Day frolic that did neither career any good.

However, a strange set of circumstances resurrected Berkeley from oblivion in the 1960s. The establishment of film studies courses on university and college campuses introduced a new generation to his masterworks from the 30s.

Suddenly, Berkeley was very much in vogue again – not as choreographer, but as an authority on technique for the lecture circuit. Embracing his rediscovery, Berkeley was asked to lampoon Berkeley in a cold tablet commercial featuring a dancing clock. In his seventy-fifth year, he also returned to Broadway to work with

old time friend and colleague, Ruby Keeler on musical sequences for No, No Nannette (1970).

old time friend and colleague, Ruby Keeler on musical sequences for No, No Nannette (1970).Berkeley’s resurrection in the public’s estimation had a rejuvenating effect on his morale. Active and admired as ‘the premiere dance architect of the Hollywood musical,’ (a fitting moniker – since Berkeley built rather than choreographed his routines) Busby Berkeley died of natural causes on March 14, 1976 in Palm Springs California. In the years since his passing, time has been extremely kind to his creations. Endlessly revived, revered and relived as an integral part of the American film tapestry since, Busby Berkeley defiantly remains that emblematic character of visionary perfectionism in light entertainment.

@Nick Zegarac 2006 (all rights reserved).