DEPARTING THE YELLOW BRICK ROAD

by Nick Zegarac

In 1939, the studio system had reached its artistic zenith: Samuel Goldwyn released his adaptation of Wuthering Heights; MGM premiered its immortal fantasy, The Wizard of Oz and David O. Selznick brought his celebrated treatment of Margaret Mitchell’s saga of the old south – Gone with the Wind to glorious and immortal Technicolor life. Make-believe did not get any better than this.

However, by the end of ‘39 a new, more subdued style in film-making began to emerge as the status quo. This trend was only partly influenced by the outbreak of World War II and the cutting off of European markets. Indeed, Hollywood’s own disenchantment with escapist fantasies mirrored the cynicism of a nation that had grown weary in its own ability to hang on to the promise of a better tomorrow.

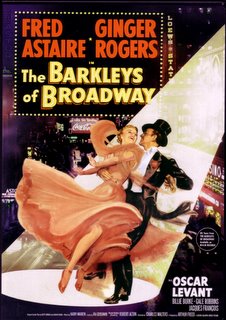

On celluloid, the shift was immediate and palpable - gone were the lavishly absurd white on white art deco sets where even the most humble of shop girls cavorted about in their champagne-bubble gowns that no genuine working gal could afford.

Instead, set and costume designers began to borrow their inspiration from downscaled stylistic trends, effectively launching the era of ‘pastiche’ – a term used to coin that nostalgic annexation and blending of styles from all periods in history.

The slick and polished dapper men in their top coats and bow ties were abandoned for guys with grit under their finger nails and the pang of hunger still lurking about their grim façades. Slowly, life on the screen began to more closely resemble life as it was generally known.

If the studios still clung to their affinity for ‘period’ picture

making, then the status of these films was quietly downgraded from swashbuckling epic to mere melodrama played out in tights and corsets. These cosmetic gestalts were complimented by a transferal in storylines.

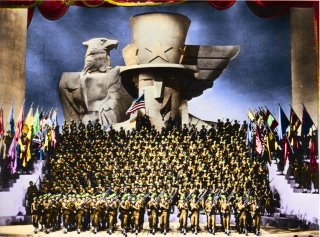

making, then the status of these films was quietly downgraded from swashbuckling epic to mere melodrama played out in tights and corsets. These cosmetic gestalts were complimented by a transferal in storylines.In general, Hollywood eschewed its affinity for ‘bigger than life’ places and people in the 1940s. The ‘30s American daydream for wealthy people living pampered lives in tiffany settings was replaced by a more dower focus on the middle class and – in some cases – the poor. At Warner Brothers, the lucrative cycle in colossal musical fantasies a la Busby Berkeley’s genius had run their course. Although Berkeley would make a transition to MGM, and later Fox, his output there in no way rivaled the carte blanche grand opulence he had been afforded at Warner.

At 20th Century-Fox, the dissipation of public interest in a grown up Shirley Temple (who, as a child star had been Fox’s number one draw in the country for four

years) meant that production chief, Darryl F. Zanuck had to find new ways to turn a profit. Zanuck chose to indulge his creative zeal for ‘message’ pictures (stories with a social commentary), made on a smaller scale and budget. Although ambitious and groundbreaking, ironically, it was Zanuck’s more frivolous musical indulgences with Alice Faye and Betty Grable that made the money for Fox.

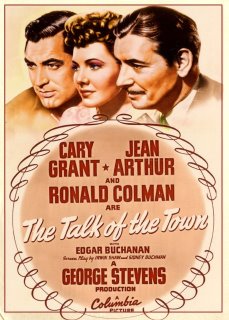

years) meant that production chief, Darryl F. Zanuck had to find new ways to turn a profit. Zanuck chose to indulge his creative zeal for ‘message’ pictures (stories with a social commentary), made on a smaller scale and budget. Although ambitious and groundbreaking, ironically, it was Zanuck’s more frivolous musical indulgences with Alice Faye and Betty Grable that made the money for Fox.Only MGM, with their motto of ‘ars gratia artis’ and bravado in proclaiming ‘more stars than there are in heaven’ managed to maintain something of that high gloss and slickly packaged entertainment that had been the hallmark of ‘30s film output. In the ‘40s, this hallmark was being billed as ‘prestige’ and not every film that emerged from the system had it. But David Selznick had ‘prestige’ in spades with his first release of

the decade: Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca. By the end of the decade, Selznick’s relentless pursuit of ‘prestige’ would all but bankrupt his studio.

the decade: Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca. By the end of the decade, Selznick’s relentless pursuit of ‘prestige’ would all but bankrupt his studio.Mid-decade, MGM’s Meet Me In St. Louis spawned a sudden affectionate reflection in turn-of-the-century nostalgia for ‘simpler times.’ So too did America’s political interests in Latin America give rise on the screen to a series of ‘south of the border’ light-hearted musical fantasies with their gaudy gauchos (Ricardo Montelbaum), swarthy lotharios (Caesar Romero) and playful caricatures (Xavier Cugat) decorating theater marquees across the country. Of particular interest and incredible popularity in this latter trend was Brazilian bombshell, Carmen Miranda who proved the most popular with her increasingly absurd headdresses and fracturing of the English language. Miranda’s presence augmented and elevated many a sub-standard musical plot to A-list good humored fun.

A question mark still remains whether or not Hollywood did its best work in the 1940s. To be certain, it did its most diverse. While the western and musical genres both continued to ‘practically’ guarantee a profit at the box office, the increasingly popular style in film was ‘noir’ – a term coined by the French to identify and quantify that darker, more perverse underbelly of Hollywood’s fantasy landscape, increasingly depicting more bleak horizons than happy endings.

The world of noir – with its femme fatales, embittered heroes and ruthless anti-heroes - mirrored the increasing isolation of a country with its own growing concerns firmly embedded in those terrible years of war, and, even more disturbed by anxieties following the return of veterans into civilian life. By the end of the decade, that darkness had seeped from the peripheries of make-believe into Hollywood at large.

The studios were flush with record-breaking swells of cash

and unprecedented weekly numbers in theater attendance. Yet, the business of making movies was being systematically deconstructed by the United States government; determined to shatter the studio’s autonomy (erroneously misperceived as monopolistic) and by HUAC (the House Un-American Activities Committee) blacklisting a goodly sample of Hollywood’s writers, directors and stars as communists or communist sympathizers. The political hearings that followed were a scathing indictment on the fear and panic that fractioned Hollywood’s artistic community – destroying careers, shattering lives and dismantling that close-knit atmosphere, once the extended families with the studio backlots doubling as artists’ home away from home.

and unprecedented weekly numbers in theater attendance. Yet, the business of making movies was being systematically deconstructed by the United States government; determined to shatter the studio’s autonomy (erroneously misperceived as monopolistic) and by HUAC (the House Un-American Activities Committee) blacklisting a goodly sample of Hollywood’s writers, directors and stars as communists or communist sympathizers. The political hearings that followed were a scathing indictment on the fear and panic that fractioned Hollywood’s artistic community – destroying careers, shattering lives and dismantling that close-knit atmosphere, once the extended families with the studio backlots doubling as artists’ home away from home. @ 2006 (all rights reserved).

@ 2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment