by Nick Zegarac

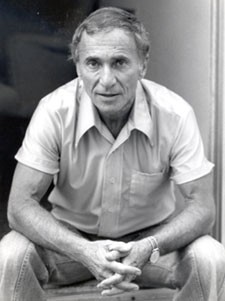

Blacklisted by HUAC during the Red Scare in Hollywood, Arthur Laurents (right) and Anastasia’s director, Anatole Litvak had shared a collaborative effort on The Snake Pit in 1948; a film whose premise was psychiatry. So Laurents came to Anastasia’s pedigree well versed in mental disease. However, after an initial meeting with Litvak in Paris, Laurents concurred that the story would function best cinematically as a fairytale.

To some extent, Laurents’ claim that all of history is merely an opinion written from a skewed perspective holds validity. “I did no (historical) research” Laurents would later confess, “…and never felt I was betraying history.” Hence, the screen’s Anastasia would not be quite as haunted or disturbed as her ‘real life’ incarnation.

As originally scripted by Laurents, the film was to have opened with the grand duchess wandering alone at night along the banks of the Seine river. In a state of depression, the woman who thinks she is Anastasia suddenly believes she hears the tinkering of a piano playing a tune from her youth. She is overcome with emotion and falls into the river, only to be rescued by passer’s by.

Litvak, however, had another idea. He wanted to open the film during Russian Easter at the Orthodox Church in Paris. Unfortunately, the church would not give its permission to film, forcing Litvak to actually build a mock up of the church on the backlot in Britain to film his grand introduction.

Casting the film version of Anastasia proved an interesting initial setback, since both Litvak and Laurents wanted Ingrid Bergman for their lead. In Hollywood, and indeed America, Bergman had been labeled persona non grata for over a decade, following her very public split from husband Peter Lindstrom and daughter Pia. Despite the fact that Bergman did not abandon her daughter (as has long since been rumored), the actress who only a decade earlier had been hailed as one of the greatest artisans in the cinema firmament had since been thrown out of the country after her affair with Italian director Roberto Rossellini. Pilloried from the pulpit and denounced in the tabloids as an unfit mother, the United States Senate took the cause of morality to new heights by banning Bergman from returning to the country as they had previously done with Charlie Chaplin.

At 20th Century Fox, then President Spyros P. Skouras urged Litvak to reconsider Bergman as his star. Barring acceptance of anyone else in the role, Skouras next suggested to Bergman that she return on a goodwill tour of the United States by visiting women’s clubs to test her in the court of popular opinion and reaction. To her credit, Bergman refused to be publicly paraded as a wanton outcast, saying, “I’m an actress…as for coming to the United States…I will come when I want to and not to be tested.”

To help bolster Bergman’s reputation, at least in the minds of Fox executives, Litvak cast First Lady of the American Theater, Helen Hayes, in the pivotal role of the Dowager Empress. Hayes had been a respected actress on Broadway before coming to Hollywood in the 1930s and winning an Oscar for her performance in The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931). However, shortly thereafter her film career had hit a snag with Louis B. Mayer that eventually resulted in her returning to the stage, which had always been her first love.

Helen Hayes had long admired Ingrid Bergman as an actress and befriended her in 1949. During this tenure, she had also married playwright and wit Charles MacArthur. The moniker, ‘first lady of the American Theater’ had been bestowed upon her in 1955 during a Broadway tribute. Reportedly, the modest actress was quite embarrassed to be thought of in such high esteem (especially since she considered contemporaries such as Katharine Cornell to be her superiors). Nevertheless, Hayes graciously accepted the honor, never believing that the title would endure. Ironically, it has.

Accolades aside, Helen Hayes had almost become a recluse by 1956. The tragedy of her only daughter’s death the previous year, coupled with the sudden loss of her husband had left her emotionally drained at the time Litvak proposed her triumphant return to motion pictures. Despite her personal apprehensions in accepting the part, Hayes was immediately welcomed into the fold on the set. She would later recall that the professional courtesies and personal acquaintances developed while working on Anastasia made for one of the most satisfying experiences she had ever had as a film actress.

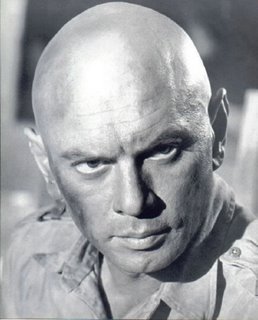

The final bit of unresolved casting for the film also proved to be the least difficult to decide upon. Everyone wanted Yul Brynner. The exotic leading man, famed for his bald pate, was in the middle of a stellar year of personal artistic accomplishments when Litvak contacted him for Anastasia. 1956 would prove to be Brynner’s seminal year as an actor. He was cast in three of the filmdom’s most spectacular and showy productions; as the Pharoh Ramsey in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments; a film reprise of his most celebrated Broadway triumph – as the king of Siam in The King & I, and as General Sergei Pavlovich Bounine in Anastasia. Though he was Oscar nominated for his role in Anastasia, Brynner lost to himself – taking home the Best Actor statuette for The King & I instead.

A delightfully rakish raconteur, Brynner shrouded much of his life in personal mysteries and myth. In truth he was born in Vladivostok on 7 July 1915, and named Yul after his grandfather. Abandoned by his own father, Brynner was a drop out at the age of 19. He became a Paris musician among the Russian gypsies, apprenticed for Jean Cocteau at the Theatre des Mathurins and doubled as a trapeze artist with Cirque d'Hiver. All of this background would serve him well as an aspiring actor during the next few years. In 1941, Brynner studied with Chekhov in the U.S. and debuted on Broadway as a Chinese peasant opposite Mary Martin in Lute Song. It was Martin who recommended Brynner to scenarists Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein. The rest…as they say, is history.

The primary appeal of Anastasia, at least for screen writer Arthur Laurents, had always been its Pygmalion aspect – the hewing of a diamond in the rough who proves to be more genuine a gem than even her Svengali had initially hoped for. To be sure, the chemistry between Yul Brynner and Ingrid Bergman was instantly palpable. In fact, during rehearsals, Brynner had developed a flirtatious crush on his Swedish costar; an assignation quickly dismantled when Bergman turned to Arthur Laurents during their run-through of the script and coolly inquired, “He’s supposed to be royalty?” Despite this initial rebuke, the two costars got on famously throughout the shoot.

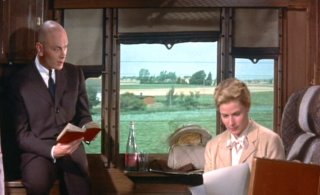

To add an air of authenticity to the production, a second film unit was sent to Copenhagen, London and Paris to photograph establishing shots that would be inserted into the final film. For all intensive purposes, however, principle cast and crew never left the sound stages, though at one point both Brynner and Berman were featured sitting inside an authentic 1920s railway car in Britain (with rear projection substituting as a moving backdrop) to depict their journey from France to Denmark.)

For the final moment in the film, in which the Dowager prods the woman she believes to be her granddaughter into following her own heart right into the arms of Gen. Bounine, Arthur Laurents had wanted Helen Hayes (when asked what she shall say to the crowd of spectators awaiting confirmation of Anastasia’s royal acceptance) to look directly into the camera and address the audience with, “I will say, the play is over. Go home.” Though the line is retained in the film’s final cut, Litvak chose instead to have Hayes speak it to her escort, Prince Paul. The conventional finale rather disappointed Laurents, who thought that his version more fittingly capped off his concept of the film; that it was a story not to be taken seriously as fact.

Upon its premiere, Anastasia (1956) was an immediate blockbuster. It marked the celebrated return of Ingrid Bergman to the big screen and earned the actress her second Best Actress Academy Award. The film also cemented Yul Brynner’s popularity at the box office. Though members of the Russian aristocracy were befuddled (and in some cases, outraged) by the artistic liberties taken, most concurred with the assessment that, as a work of pure fiction, the film held up remarkably well under narrative scrutiny.

If the film had any negative publicity, it derived from resurgence in public interest for Anna Anderson (right) – the woman who had retreated from public life to a cottage deep in Germany’s Black Forest. Endlessly besought by reporters hungry for a sound byte, Anna eventually fled her home to the United States in 1968. It was her second trip abroad.

In the late 1920s, Anderson had been the guest of Princess Xenia in Manhattan – a short lived association that ended when Anna stripped naked and danced about the roof top of Xenia’s fashionable penthouse apartment. Institutionalized once more and shipped back to Germany in 1940, Anderson had been content to live her life in private until her return visit to the U.S.

In 1968, Anderson met and married a Charlottesville Virginia university professor. But her personal demons refused to perish. Living in squalor and plagued by her chronic bouts of depression, Anderson was eventually institutionalized once more in 1983. She died on February 12, 1984. Through advanced DNA sampling, taken before her death and matched with a sample from England’s Prince Philip, scientists conclusively determined that the woman who had so cleverly defied any finite labeling of her own identity while she lived was actually NOT the grand duchess Anastasia.

And so at the end of a journey, that began with one of the most tragic disappearing acts in all of 20th century history the whereabouts of the real Anastasia (and that of her brother) are still unknown. Film fantasies aside, as time wears on, Anastasia will probably remain an enigma for the ages.

Did she survive? It’s the rumor…the legend…and the mystery.

@ 2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment