by Nick Zegarac

The rumor, the legend and the mystery of Anastasia has very little to do with her perishable truth, perhaps because historians remain divided as to what actually became of the grand duchess after one bloody night in 1917. Since then, Anastasia has been immortalized as a Broadway smash, an Oscar-winning film, and, a musical cartoon; all cardboard cut out variations on the fairytale princess model: an irony that has all but eclipsed the sad unromantic, and as yet, unsolved imperial puzzle. If any fabled correlation can be drawn from the story of Anastasia, it is as the antithesis of a fairytale - the epitome of a tragic and brutal nightmare, so heinous and haunting that the immensity of its atrocity continues to stagger the heart and confound the mind to this day.

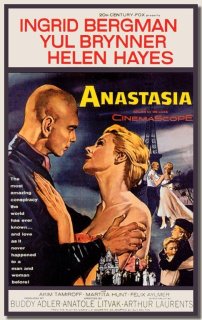

In re-conceptualizing Anastasia’s life as high art, director Anatole Litvak’s 1956 melodrama eschewed fact in favor of total

fabrication, modeled on the Cinderella-like transformation from cast off waif to classy aristocrat. It is this rich tapestry cinematically woven by Litvak and spun from the romanticized yarns penned by Arthur Laurents that continue to generate much of the grand duchess’s timeless mythology. In the film, Anastasia the princess, who may or may not have died in vane along with the rest of her family during the slaughter in 1917, is no longer her own person. She has become the star turn, a slate of artistic ambiguity upon which artisans and a Hollywood icon, Ingrid Bergman have inscribed the tale we, as an audience, would rather believe.

fabrication, modeled on the Cinderella-like transformation from cast off waif to classy aristocrat. It is this rich tapestry cinematically woven by Litvak and spun from the romanticized yarns penned by Arthur Laurents that continue to generate much of the grand duchess’s timeless mythology. In the film, Anastasia the princess, who may or may not have died in vane along with the rest of her family during the slaughter in 1917, is no longer her own person. She has become the star turn, a slate of artistic ambiguity upon which artisans and a Hollywood icon, Ingrid Bergman have inscribed the tale we, as an audience, would rather believe.It was this fervent desire to daydream beyond what little is actually known about those final moments in a young life that was well in tune with Litvak’s own Russian Jewish heritage. A man of impeccable manners, graciousness and meticulous attention to detail, Litvak had been a premiere director at Germany’s UFA Studios prior to the rise of Adolph Hitler. His 1936 film, Mayerling (shot in France) brought him to the attention of Hollywood.

While in France, Litvak had been privy to that longing for a return of the royal family by some of the exiled Russian aristocrats living out their glorious golden days in the squalor of remnant enclaves within Berlin and Paris. So desperate were these refugees for a return to their homeland – and reinstatement of their titles and lands – that they eagerly embraced a litany of would-be princesses; pretenders to the throne masquerading for their own share of a rumored inheritance hidden in the Bank of England during those formative years immediately following the revolution.

The real Anastasia Nikolayevna (above) was born to a life of wealth and privilege on June 18th, 1901. She was the youngest daughter of the first (and last) 20th century king of Russia; Czar Nicholas Romanov II (below) and his wife Czarina Alexandra Feodorovna. A bit of a tomboy and something of a prankster, Anastasia’s sublime world of culture and wealth was spent being educated in languages and the arts, and, indulging in lavish vacations both at home and abroad; but it was a fragile existence that was not to last.

Despite being a formidable intellectual with an extensive military background, the Czar was both something of a recluse and an autocrat. This distance from his people – who regarded their Czar as a ruler ordained by God - helped to perpetuate the mystique of the monarchy which, at the start of Nicholas’s reign, had enjoyed an unprecedented popularity.

Indeed, the Romanovs were celebrating 300 years of their family bloodline on the throne. However, at a time when other countries (most notable, Britain) were adopting constitutional monarchies, the Czar continued to rule Russia with an iron fist and, some would argue, obliviousness to the suffrage and poverty of more than eighty percent of the populace over which he held dominion.

In 1914, Nicholas declared war on Germany – a move that proved his undoing. For although the Czar placed his country’s pride and welfare at the forefront of foreign affairs, he was ill equipped as either a visionary military man or diplomatist to see his plans through. Assuming command of

the armed forces, Nicholas and his army endured one defeat after the next against the Germans.

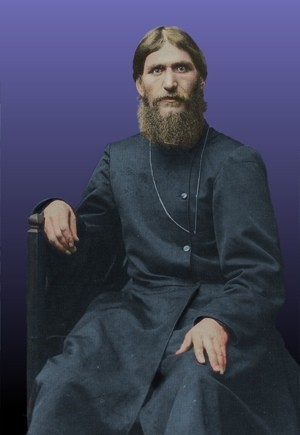

the armed forces, Nicholas and his army endured one defeat after the next against the Germans.At home, the Czarina’s growing dependency on a monk of spurious reputation, Grigory Rasputin had begun to erode the royal family’s popularity with the masses. Indeed, Rasputin proved to be a self-indulgent womanizer and a drunk. However, he also seemed to be in possession of some strange mystical power that quelled the hemophilia plaguing the future heir to the throne, Alexei Nikolaievich.

Little is known about the grand duchess Anastasia during this time, except that at the age of twelve she had already become something of a gifted photographer, indulging her craft in family snapshots before becoming a war nurse and tending to the wounded along with the rest of her sisters.

The Bolshevik party headed by Vladimir Lenin seized power and forced the abdication of the Czar. Exiled to the remote Siberian town of Ekaterinburg and “the house of special purpose” (a euphemism for the place of execution), the Czar and ten others were exterminated in a hale of gunfire on the 16th of July 1918. To discourage any royalists from recovering their remains (as religious artifacts) the bodies were bayoneted, stripped naked, doused in gasoline and sulfuric acid and lit afire before being buried in unmarked graves somewhere in the forest beyond the “house of special purpose.”

But were they really dead?

Newspaper reports of the day ran the gamut of wild speculation; from everyone surviving and being exiled in the Far East, to total annihilation. In retrospect, it seems that neither journalistic claim was true.

Although an extensive excavation recovered bones from the earth in 1991, the dig only served to highlight a mystery which had been ongoing almost from the moment of assassination: that Anastasia had maybe survived.

Indeed, while forensic experts were able to piece together nine bodies buried beyond the “house,” neither Anastasia nor Alexei were among the remains. It seems highly unlikely that in the moments of haste immediately following the execution that any special attention would have been placed on relocating the two youngest victims to an alternative burial site. Hence, the speculation and the hope of all royalists from that time onward has long since been that both children escaped their preordained fates.

As early as 1920, pretenders to the throne had begun popping up all over Europe. One struck an indelible impression: Anna Anderson(right). Tuberculosis stricken, Anderson’s checkered past included several suicide attempts and frequent institutionalizations for various mental disorders.

It was during her stay at one of these asylums in France that Anna confided to a fellow patient that she was the daughter of Czar Nicholas II. So compelling was Anderson’s ability to recall specifics (arguably, that no one else other than the real Anastasia could have possibly known) that many in the Russian émigré communities peppered throughout the rest of Europe believed Anna’s story and began launching law suits on her behalf to reclaim her title as grand duchess.

Indeed, it was Anderson’s life thus far that became the fodder for skilled Parisian playwright, Marcelle Maurette’s intercontinental smash play, transcribed for the Broadway stage by scenarist Guy Bolton. Since no one knew the whereabouts of the real grand duchess it became quite feasible to assume that Anderson was the real McCoy. However, in translating the play into a film, screen writer Arthur Laurents made several key changes to the narrative that – although entirely

void of historical fact – generated great melodrama for the big screen. These changes included a pivotal confrontation and reconciliation between Anna and her grandmother, the Dowager Empress Marie. In reality, although the real Anastasia’s aunt Olga did travel to France to visit Anna Anderson while she recovered from tuberculosis, no such public approval or acceptance of Anna – either by Olga or the Dowager Empress ever transpired. In fact, the Empress and Anna never met in real life.

void of historical fact – generated great melodrama for the big screen. These changes included a pivotal confrontation and reconciliation between Anna and her grandmother, the Dowager Empress Marie. In reality, although the real Anastasia’s aunt Olga did travel to France to visit Anna Anderson while she recovered from tuberculosis, no such public approval or acceptance of Anna – either by Olga or the Dowager Empress ever transpired. In fact, the Empress and Anna never met in real life.

No comments:

Post a Comment