1945 By the end of May, armistice had been achieved in Europe. Hollywood’s film community naively assumed that at wars’ end its supremacy as the sole purveyors of mass entertainment would be restored. Their output for the year reflected this optimism. State Fair, a glossy remake of the old Will Rogers film with new songs by Rodgers and Hammerstein, and co-starring the winsome Jean Crain as a fresh faced farm girl who finds love on the midway in the arms of news hound Dana Andrews, was a big winner for Fox. Popular too was Cornel Wilde’s turn as Chopin in A Song to Remember. Unfortunately, no amount of musical prowess could stop Warner Brothers’ costly Rhapsody in Blue from becoming a box office flop.

MGM threw all its resources behind Anchors Aweigh – an effervescent musical that marked the film debut of Frank Sinatra. It was nominated as Best Picture but lost to The Lost Weekend – a grim depiction of alcoholism; perhaps foreshadowing the fact that audiences were starting to demand more realism from their motion pictures.

Treacle was still in: Leo McCarey’s The Bells of St. Mary’s was a magnificent tear jerker that rang registers around the country. Hitchcock dazzled once again with Spellbound. Ingrid Bergman’s involvement in that film won her the Best Actress New York Film Critic honors. Joan Crawford – who had been labeled a has-been by L.B. Mayer at MGM, migrated to Warner Brothers and won the Best Actress Oscar for her performance in Mildred Pierce, a greatly sanitized version of the scathing James Cain novel.

Actress Olivia deHavilland won her landmark case against alma mater Warner Brothers. Charging that she had been strong armed into a contract extension of six months (to compensate for her suspension), the Supreme Court ruled that the maximum term any studio could ‘hold’ a star under contract was seven years – including periods of suspension.

Total unknown, Hurd Hatfield burst onto the screen with a resounding success in The Picture of Dorian Gray – a salacious melodrama about a young man whose wicked debaucheries in life ravage his portrait though not his corps. Even fresh-faced Deanna Durbin eschewed her usual cheery conventions for Lady on a Train – a murder mystery in which Ms. Durbin nevertheless found several choice moments to sing.

Zanuck managed a minor coup with The House on 92nd Street, a film shot on location in and around Washington D.C. and afforded audiences unprecedented access to the inner workings of the F.B.I. One of the most impressive yet underrated achievements of the year was Vincente Minnelli’s The Clock – a poignant war time romance that did solid box office. Rory Calhoun became the latest beefcake heartthrob – mostly for his shirtless fight scene in Nob Hill. Danny Kaye did it better - strictly for laughs in the comedy of errors; Wonder Man. Memorable character actors, Alla Nazimova and Gabby Hayes died.

1946 Apart from William Wyler’s poignant account of returning war veterans, The Best Years of Our Lives (which took home the Best Picture Oscar) the year was marked by a decidedly indifferent batch of film product that generally failed to catch the public’s fascination in anything but moderate box office returns. MGM’s grandiose anniversary flick, Ziegfeld Follies became a super production mired in bad taste; a hodgepodge of stars cavorting in garish costumes on gaudy sets. On the whole, the studio’s other musical offering; Till The Clouds Roll By faired much better – both artistically and financially. Roberto Rossellini’s Open City served a two fold purpose: it introduced Italian actress Anna Magnani to American audiences and ushered in the influential post-war neo-classic style in film making.

Laurence Olivier produced, starred and directed Henry V – more an artistic than financial triumph. In Hollywood, The Yearling, costarring Gregory Peck and Jane Wyman was a particularly bit of homespun fluff (about a boy and his deer) that caught on. Fox and director John Ford produced the seminal western My Darling Clementine. Warner Brothers and Joan Crawford continued their lucrative association with Humoresque, the May/December embittered tale of tempestuous love between a haughty diva and her headstrong violinist. The noir cycle was in full swing with Rita Hayworth’s scintillating Gilda and Hitchcock’s sublime espionage thriller, Notorious. The on screen chemistry between Lana Turner and John Garfield scorched the screen in James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, even though their behind the scenes animosity proved that mutual romantic admiration a myth.

On the whole, one of Hollywood’s best loved genres – the musical was not performing up to expectation. Disney’s attempt at a live action/animated feature – Song of the South played upon black stereotypes and good natured fables for its fodder, but was only a minor success. MGM’s lavish Du Barry Was A Lady flopped: ditto for Warner’s Night and Day – a thoroughly fictionalized account of composer Cole Porter’s life.

Frank Capra produced and directed It’s a Wonderful Life for his own co-founded Liberty Films. The film’s tepid box office response effectively closed the fledgling studio. Though sumptuously mounted, both RKO’s Caesar and Cleopatra and 20th Century Fox’s The Razor’s Edge were only moderately received. Fox’s other lavish epic of the year, Anna and the King of Siam made Britain’s Rex Harrison an international heartthrob – nicknamed ‘sexy Rexy’. The artistic community mourned the losses of character actor George Arliss and cynical comedian W.C. Fields.

1947 can effectively be considered a year of considerable change in the status quo of making movies. In hindsight, director Ernest Lubitsch’s death seems to have marked the bitter end of Hollywood’s carefree romantic champagne. The production code was revised to explicitly ban any movie from illustrating a crime unless the reprobates in question were depicted as paying a price for their indiscretion. Charlie Chaplin was branded un-American by HUAC. The committee also blacklisted director Edward Dmytrk for his involvement on Crossfire.

Though the industry desperately tried to hang on to its supremacy – its failure to adapt with changing times resulted in many films that – although made with the best of intentions, were quite out of step with public tastes. Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy’s usually solid teaming floundered in The Sea of Grass. The costume melodrama, Song of Love (also with Hepburn) failed to catch on. Douglas Fairbanks Jr. tried to relive his father’s glory in Sinbad the Sailor – and was decried as inferior in all respects.

The Hollywood studios continued to be dominated by their tyrannical moguls and top heavy producer model. But the biggest news in the industry was the invasion of Brit’ J. Arthur Rank. A prolific tycoon, Rank had effectively telescoped Universal International’s merger with United World Pictures. At home, Rank was also busy constructing his own filmic empire – responsible for a litany of crafted product well received on both continents. Odd Man Out, Black Narcissus, This Happy Breed and adaptations of Nicholas Nickleby and Great Expectations were intercontinental successes.

At Fox, Darryl F. Zanuck’s dream factory had an uneven slate of projects. Zanuck scored a financial and critical success with his critique of anti-Semitism in Gentlemen’s Agreement, though in retrospect, RKO’s more modestly budgeted (and like themed) Crossfire seems a more effective film. Fox also had an unlikely hit with A Miracle on 34th Street – unlikely because the Christmas film was unceremoniously dumped on the market in mid-July, but managed to become the summer season’s runaway hit – all about a department store Santa who thinks he’s the real deal. Three best selling novels were transformed into three extremely disappointing movies: The Late George Apley, The Egg and I and Forever Amber. The latter was a costly flop about a maniacal courtesan played by Fox lovely, Linda Darnell. However, most of Amber’s naughtiness had been usurped by the censors.

Marlene Dietrich had a thoroughly abysmal failure on her hands with Golden Earrings in which she played a gypsy princess. Cary Grant faired reasonably well with The Bachelor and the Bobbysoxer – a quaint family comedy about a young girl’s infatuation with a middle age lady’s man. Joan Crawford continued her upswing at Warner Brothers in Possessed, the tale of a mentally deranged woman on the verge of a breakdown. Charlie Chaplin’s perverse little comedy, Monsieur Verdoux outraged most critics – not for its content, but because Chaplin was by this point branded a communist by HUAC.

1948 Laurence Olivier briefly made Bill Shakespeare’s prose (and acting in tights) fashionable again with his Oscar-winning Hamlet. From Britain also came Moira Shearer’s international debut in Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes – a ballet orientated film about the tragic dichotomy between love and art. From France, Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast was an effective rendering of the fairytale with sumptuous sets and lavish costumes. However, this verve for the classics did not rub off on Columbia’s The Loves of Carmen – an expensive but abysmal Hollywood update of Bizet’s tale, this time starring Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford. Ill-received too was Ingrid Bergman’s performance as the title character in Joan of Arc.

The New York Film Critics gave their accolades to Warner Brother’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre – one of two landmark Bogart pictures of the year (the other being, Key Largo). The novel Treasure of the Sierra Madre was written by B. Traven – a man more myth than flesh and blood and equally elusive after cameras had stopped rolling. Orson Welles infuriated Columbia President, Harry Cohn by bleaching Rita Hayworth’s trademark red tresses blonde for The Lady from Shanghai; another attempt by Welles at greatness that was sadly butchered by cuts after Welles had departed the studio. The film was unceremoniously dumped on the market to lackluster reviews and public response though, like many of Welles’ films, it is today considered a classic.

Darryl F. Zanuck continued his relentless pursuit of stories with substance with The Snake Pit – a critical examination of mental illness and asylums. Barbara Stanwyck convincingly portrayed an invalid who overhears, but is unable to intervene in, a murder plot in Sorry Wrong Number. Ray Milland played a man wrongfully accused of murder in the noir thriller, The Big Clock. Larger than life John Wayne and newcomer to films Montgomery Clift spared against the viral backdrop of Indian country in Red River.

On the lighter side, and from MGM, came Easter Parade – Fred Astaire’s most delightful post RKO teaming with the studio’s own musical titan, Judy Garland. Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn were back on top with Frank Capra’s State of the Union – a scathing political comedy/drama. But the outstanding acting performance by an actress this year was Jane Wyman in Johnny Belinda. Playing a deaf mute, Wyman managed to convey a sensitivity and sensibility in her performance. One of the most influential of all Hollywood pioneers, David W. Griffith died alone and forgotten. Death also claimed the lives of Dame May Whitty, King Baggot and one of Hollywood’s most promising young stars, Carole Landis who committed suicide with an overdose of seconal at the age of 29. She had 49 films to her credit.

1949 The decade concluded on a rather dower note of distinction. While several of the year’s offerings were noteworthy for their examination of racial issues (Pinky, Intruder in the Dust, Home of the Brave), the bulk of the yearly output played it safe with mediocre themes, and, as a result, came up with mediocre returns.

The Best Picture of the year was decidedly All The King’s Men – a scarring indictment of politics corrupting a proud man. Long denied the Oscar for her body of work, Olivia deHavilland took home the award for her brutally cold performance in The Heiress – all about a wallflower whose father’s meddling ruins her only chance at happiness. James Cagney reemerged in the gangster genre that had made him famous a decade earlier, in a perverse tale of betrayal and deception – White Heat.

Suffering from the ravages of a life filled with carousing, no amount of makeup could mask the wear and tear on Errol Flynn as he meandered through his final success, The Adventures of Don Juan. The Disney stable marked a return to excellence with Cinderella – a magical retelling of the fairytale through the use of pop songs and the stunning art of animation. MGM – known for their impeccable roster of musical comedy stars launched Mario Lanza in a remarkable film debut, That Midnight Kiss; an unremarkable film costarring Kathryn Grayson. MGM also reunited Fred Astaire with Ginger Rogers for The Barkleys of Broadway – a film that unequivocally proved that the good old days for this team were decidedly a thing of the past. Judy Garland and Van Johnson costarred in a remake of The Shop Around the Corner (renamed In The Good Ol’ Summertime). Esther Williams and Red Skelton tried to recapture the magic of Bathing Beauty with Neptune’s Daughter – a dismal waterlogged flick whose only distinction is that it features the Oscar-winning song ‘Baby It’s Cold Outside.’ MGM had more financial success with its remake of Little Women – this time costarring June Allyson, Elizabeth Taylor, Janet Leigh, Mary Astor and Peter Lawford. The film proved to be C. Aubrey Smith’s last. The much beloved character actor died of pneumonia later that year.

Death also robbed the artistic community of directors Victor Fleming and Sam Wood, as well as acting greats Richard Dix and Wallace Beery. Writer/director Joseph L. Mankewicz would emerge triumphant the following year with two Oscars for writing and directing A Letter to Three Wives – already playing in theaters. Fox’s other notable entry of 1949, Come to the Stable proved an enchanting and lighthearted fable costarring Celeste Holm and Loretta Young.

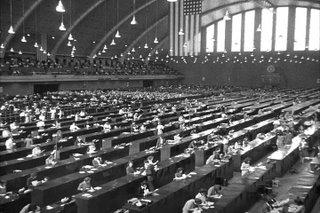

In retrospect, it seems unlikely that any of the studio moguls could foresee how much of an impact television was to have on their entertainment empire in the next decade. Although first experimented with at the New York World’s Fair just prior to the outbreak of WWII, television remained a quiet footnote throughout the 1940s. T.V. was, however, to shortly be transformed through cash investment and the rise of baby boomer/suburbian migration away from the major cities, into the movies greatest arch nemesis. For all intensive purposes then, the 1940s were the last decade in which the movies dominated American culture as the supreme form of mass entertainment.

@2006 (all rights reserved).