"SUNDAY MORNING": THE MASS OF WALLACE STEVENS

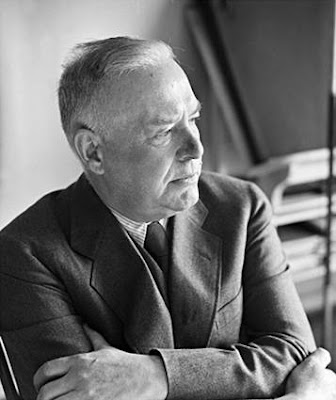

I originally wrote this essay for the exacting eye of Professor Carlos Baker of the Princeton English department in March 1975 while a sophomore. The leading Hemingway authority at the time, Carlos was teaching a course in Modern Literature, and I chose to write about one of the greatest and most beautiful poems of the twentieth century, Wallace Stevens’ “Sunday Morning,” a poem that ranks with Eliot’s “The Waste Land” and Yeats’ “The Second Coming" as a masterful achievement of literary modernism.

According to his kids, he came home from the office, closed the door to his private study, and wrote poetry; they never saw him.

According to his kids, he came home from the office, closed the door to his private study, and wrote poetry; they never saw him.

To make my essay easier to understand, I’m reproducing Stevens’ actual poem “Sunday Morning” both before and after my essay, so you’ll have a chance to appreciate what I’m talking about when I refer to specific passages. “Sunday Morning” is a supremely beautiful poem, and I think you’ll enjoy reading it.

Sunday Morning

1

Complacencies of the peignoir, and late

Coffee and oranges in a sunny chair,

And the green freedom of a cockatoo

Upon a rug mingle to dissipate

The holy hush of ancient sacrifice.

She dreams a little, and she feels the dark

Encroachment of that old catastrophe,

As a calm darkens among water-lights.

The pungent oranges and bright, green wings

Seem things in some procession of the dead,

Winding across wide water, without sound.

The day is like wide water, without sound.

Stilled for the passing of her dreaming feet

Over the seas, to silent

Dominion of the blood and sepulchre.

2

Why should she give her bounty to the dead?

What is divinity if it can come

Only in silent shadows and in dreams?

Shall she not find in comforts of the sun,

In pungent fruit and bright green wings, or else

In any balm or beauty of the earth,

Things to be cherished like the thought of heaven?

Divinity must live within herself:

Passions of rain, or moods in falling snow;

Grievings in loneliness, or unsubdued

Elations when the forest blooms; gusty

Emotions on wet roads on autumn nights;

All pleasures and all pains, remembering

The bough of summer and the winter branch.

These are the measures destined for her soul.

3

Jove in the clouds had his inhuman birth.

No mother suckled him, no sweet land gave

Large-mannered motions to his mythy mind.

He moved among us, as a muttering king,

Magnificent, would move among his hinds,

Until our blood, commingling, virginal,

With heaven, brought such requital to desire

The very hinds discerned it, in a star.

Shall our blood fail? Or shall it come to be

The blood of paradise? And shall the earth

Seem all of paradise that we shall know?

The sky will be much friendlier then than now,

A part of labor and a part of pain,

And next in glory to enduring love,

Not this dividing and indifferent blue.

"The Palm at the End of the Mind" is both the title of one of Stevens' most famed poems and a popular collection of his works

"The Palm at the End of the Mind" is both the title of one of Stevens' most famed poems and a popular collection of his works

4

She says, "I am content when wakened birds,

Before they fly, test the reality

Of misty fields, by their sweet questionings;

But when the birds are gone, and their warm fields

Return no more, where, then, is paradise?"

There is not any haunt of prophecy,

Nor any old chimera of the grave,

Neither the golden underground, nor isle

Melodious, where spirits gat them home,

Nor visionary south, nor cloudy palm

Remote on heaven's hill, that has endured

As April's green endures; or will endure

Like her remembrance of awakened birds,

Or her desire for June and evening, tipped

By the consummation of the swallow's wings.

5

She says, "But in contentment I still feel

The need of some imperishable bliss."

Death is the mother of beauty; hence from her,

Alone, shall come fulfillment to our dreams

And our desires. Although she strews the leaves

Of sure obliteration on our paths,

The path sick sorrow took, the many paths

Where triumph rang its brassy phrase, or love

Whispered a little out of tenderness,

She makes the willow shiver in the sun

For maidens who were wont to sit and gaze

Upon the grass, relinquished to their feet.

She causes boys to pile new plums and pears

On disregarded plate. The maidens taste

And stray impassioned in the littering leaves.

6

Is there no change of death in paradise?

Does ripe fruit never fall? Or do the boughs

Hang always heavy in that perfect sky,

Unchanging, yet so like our perishing earth,

With rivers like our own that seek for seas

They never find, the same receding shores

That never touch with inarticulate pang?

Why set pear upon those river-banks

Or spice the shores with odors of the plum?

Alas, that they should wear our colors there,

The silken weavings of our afternoons,

And pick the strings of our insipid lutes!

Death is the mother of beauty, mystical,

Within whose burning bosom we devise

Our earthly mothers waiting, sleeplessly.

7

Supple and turbulent, a ring of men

Shall chant in orgy on a summer morn

Their boisterous devotion to the sun,

Not as a god, but as a god might be,

Naked among them, like a savage source.

Their chant shall be a chant of paradise,

Out of their blood, returning to the sky;

And in their chant shall enter, voice by voice,

The windy lake wherein their lord delights,

The trees, like serafin, and echoing hills,

That choir among themselves long afterward.

They shall know well the heavenly fellowship

Of men that perish and of summer morn.

And whence they came and whither they shall go

The dew upon their feet shall manifest.

8

She hears, upon that water without sound,

A voice that cries, "The tomb in

Is not the porch of spirits lingering.

It is the grave of Jesus, where he lay."

We live in an old chaos of the sun,

Or old dependency of day and night,

Or island solitude, unsponsored, free,

Of that wide water, inescapable.

Deer walk upon our mountains, and the quail

Whistle about us their spontaneous cries;

Sweet berries ripen in the wilderness;

And, in the isolation of the sky,

At evening, casual flocks of pigeons make

Ambiguous undulations as they sink,

Downward to darkness, on extended wings.

Listen to Freddie Hubbard's beautiful jazz composition "Sky Dive," which captures the rapture and tenderness of "Sunday Morning." The birds swoop

"SUNDAY MORNING": THE MASS OF WALLACE STEVENS

"After one has abandoned a belief in god [sic]," Wallace Stevens wrote in the "Adagio" section of aphorisms published in Opus Posthumous, "poetry is that essence which takes its place as life's redemption." (1) Nowhere does he better express his conviction that art is the religion of the creative personality than in his 1915 poem "Sunday Morning."

"In an age of disbelief, or, what is the same thing, in a time that is largely humanistic, in one sense or another, it is for the poet to supply the satisfactions of belief, in his measure and his style," Stevens wrote. (2) How does he supply these satisfactions?

Largely, “Sunday Morning” is the artistic realization of the poetic dictum he set forth that constitutes the credo of his artistic religion: "The relation of art to life is of the first importance especially in a skeptical age since, in the absence of a belief in God, the mind turns to its own creations and examines them, not alone from the aesthetic point of view, but for what they reveal, for what they validate and invalidate, for the support that they give." (3) In "Sunday Morning," the mind's search for these supports is as much Stevens' as the woman' s.

"Sunday Morning" takes the form of a woman's musings on a Sunday morning. Stevens uses her as the projection of his consciousness as he used the Third Girl to voice his feelings in "The Plot Against the Giant." She leads a life of comfort, as did Stevens and as do many of his middle-class readers, and so she feels guilty enjoying the breakfast: "Complacencies of the peignoir and late/Coffee and oranges in a sunny chair” while the devout attend Mass.

While her thoughts drift and she reflects on the Passion, her mind focuses on Via Dolorosa’s morbid aspects, which make worship distasteful to her: "She dreams a little and she feels the dark/Encroachment of that old catastrophe" and, "The pungent oranges and bright, green wings/Seem things in some procession of the dead” as she reflects on "silent Palestine, /Dominion of the blood and sepulchre." (Italics mine.) As the poet asks at the beginning of Stanza II, "Why should she give her bounty to the dead?"

Stevens offers fragments scattered throughout the poem that, when pieced together, present a cohesive picture of the moral universe in which the poem is set. As he writes,

We live in an old chaos of the sun,

Or old dependency of day and night,

Or island solitude, unsponsored, free,

Of that wide water, inescapable. (Stanza VIII)

rivers like our own that seek for seas

They never find, the same receding shores

That never touch with inarticulate pang. (Stanza VI)

How does the poet propose that this spiritual hunger be fed? In Stanza II, rejecting sacrifice to "the dead"—meaning both Christ and the religion He founded—he provides for her "Things to be cherished like the thought of heaven" in the secular joys of the "balm and beauty of the earth." "All pleasures and all pains," "These are the measures destined for her soul."

When the poet begins Stanza III with the assertion, "Jove in the clouds had his inhuman birth," he means, "The people, not the priests, made the gods." (4) Absorbing the force of our own creation ("our blood, commingling, virginal/With heaven"), we so hungered for another, newer god that we created one in Jesus Christ, and our wish "brought such requital to desire/The very hinds discerned it, in a star."

"Now that myth, like all myths, has lost its compelling force,'' Stevens observed. (5) So that when he says,

Shall our blood fail? Or shall it come to be

The blood of paradise? And shall the earth

Seem all of paradise that we shall know?

he is drawing from the line in the preceding stanza, "Divinity must live within herself," in the hope that man will realize that his blood, without the intercession of any deity, is so precious as to be divine. If only we can realize that, then

The sky will be much friendlier then than now,

A part of labor and a part of pain,

And next in glory to enduring love,

Not this dividing and indifferent blue.

In Stanza IV, the poet answers the woman's doubts of an afterlife by discarding the "silent shadows and dreams" of past paradises in favor of peaceful memories and the enduring cycle of the return of spring. In Stanza V, in answer to her need of "some imperishable bliss" in the present, he offers the pleasure tinged with sadness we receive from enjoying life, which we know will pass so quickly, and which is full of things we love that we know will also fade:

Alone, shall come fulfillment to our dreams

And our desires.

Like Eliot in "The Fire Sermon" of The Waste Land, Stevens identifies sex as the force through which life expresses itself; and one of life’s great pleasures is desire, which we feel when confronted with its opposite, death.

Goya's "Saturn Devouring His Son"

Regarding Death, he says,

She causes boys to pile new plums and pears

On disregarded plate. The maidens taste

And stray impassioned in the littering leaves.

"Lady Lilith" by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

It is as if the plums and pears, products of the fertility that nature has brought to the spring, served as an aphrodisiac for the maidens. Unspoken is the comment that the "dead" religion of Christianity has failed to provide a fertility rite to serve as an outlet for these natural impulses.

Does ripe fruit never fall? Or do the boughs

Hang always heavy in that perfect sky,

Unchanging...

Alas, that they should wear our colors there....

And pick the strings of our insipid lutes:

The idea becomes the more ridiculous when we realize that the laws of nature present such a mystery to us that we must ask the question, "Why set the pear upon those river-beds/Or spice the shores with the odors of the plum?" But Stevens understands why we form such misconceptions:

Death is the mother of beauty, mystical,

Within whose burning bosom we devise

Our earthly mothers waiting, sleeplessly.

In the face of the mystery of death, we can only create comforting illusions based on earthly sights and scenes.

Stanza VII, presenting Stevens’ only substitute for paradise that has religious overtones, provides his idealized alternative, in symbolic form. Our new object of devotion, he is saying, should be as the sun god is to his worshippers; he is a source and a symbol of life, and they as votaries are "Supple and turbulent," not rigid and reserved, in their celebration. Stevens offers the source of consolation they turn to as an example for us. It is

Naked among them, like a savage source.

Their chant shall be a chant of paradise,

Out of their blood, returning to the sky....

They shall know well the heavenly fellowship

Of men that perish and of summer morn.

And whence they come and whither they shall go

The dew upon their feet shall manifest.

For them the sky is "A part of labor and a part of pain." They shall know the fellowship of men that have perished, because they are men that have lived. As for the two cryptic lines that end the stanza, the men have dew upon their feet because their bare feet (their naked freedom) have trod the earth in the morning, during the new day they are setting out to create. Their progress can be charted by their wet footprints, because these are men who live in the physical world and who are concerned with the present, not with life after death. Stevens hints that we should live with the same attitude as these men.

With Stanza VIII, the woman's mind returns from the realm of her imagination ("that wide water without sound") with a dramatic realization from within that dispels any mystical trappings from the Passion. As it dawns upon her, after her concentrated reverie, that she is living in an age whose idols have passed their twilight, where she must choose between existence in a quotidian world and spending a life alone, she comes to accept the wonders of life that nature has surrounded her with, and she accepts the ambiguous fate of the swallows, which is tied into two preceding images.

First, she realizes that she enjoys "the green freedom of the cockatoo" of Stanza I. Second, in the last stanza, the pigeons, like the swallows of Stanza IV, are diving into the evening (the "darkness" of Stanza VIII). In Stanza IV, the wings are in a state of "consummation"; in Stanza VIII they are "extended." In both cases, the birds are making their descent into the darkness with wings spread out like outstretched arms, a symbol of acceptance.

Justin was meeting his fate. For a brief moment I caught a fleeting glimpse of the Lamb of Wilmington as he shot over the crashing falls in the deepening dusk. In that second his rippling body was perfectly outlined against the violet twilight. His arms were flung out in a generous embrace, like wings outspreading. Head thrown back, he was still belting out his exultant cry—a rebel yell, almost a joyous alleluia! That moment is forever imprinted in my memory. I will never forget the wonderful sight of Justin rushing to his death, unafraid, triumphant. That's how I'll always remember him—rearing back, poised on the brink of the waterfall, like an ecstatic Cowboy astride a bucking bronco he has just broken. Then the stop-action frame jerked and he vanished and the rolling thunder of the water swallowed him up.

Like the birds in flight, plunging into the unknown, Stevens is saying, we too must move into the dark mystery waiting for us, whether it is the future or death. The old gods are dead; and we, privileged to live in an age where we can mold the gods of the age to come, must grope through the shadows, accepting life as justifying its own worth, in search of our personal gods who will make our lives worth living.

Many believe Wallace Stevens wrote his acclaimed poem “The Man With the Blue Guitar” after viewing Picasso’s “Old Guitarist”

For Wallace Stevens it was enough to impart this belief to us in beautiful, vivid, compressed language that produced a magnificent poem. He made his muse—poetry—his god. His art was his religion. And the finest example of his devotion is "Sunday Morning."

ENDNOTES

- Wallace Stevens, Opus Posthumous (New York, 1957), p. 158.

- Ibid., p. 206.

- Ibid., p. 259.

- Ibid., p. 208.

- A. Walton Litz, Introspective Voyager (New York, 1972). p. 47.

"Sunday Morning" originally appeared in Stevens' landmark 1923 collection, Harmonium

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Litz, A. Waiton. Introspective Voyager.

Sunday Morning

1

Complacencies of the peignoir, and late

Coffee and oranges in a sunny chair,

And the green freedom of a cockatoo

Upon a rug mingle to dissipate

The holy hush of ancient sacrifice.

She dreams a little, and she feels the dark

Encroachment of that old catastrophe,

As a calm darkens among water-lights.

The pungent oranges and bright, green wings

Seem things in some procession of the dead,

Winding across wide water, without sound.

The day is like wide water, without sound.

Stilled for the passing of her dreaming feet

Over the seas, to silent

Dominion of the blood and sepulchre.

2

Why should she give her bounty to the dead?

What is divinity if it can come

Only in silent shadows and in dreams?

Shall she not find in comforts of the sun,

In pungent fruit and bright green wings, or else

In any balm or beauty of the earth,

Things to be cherished like the thought of heaven?

Divinity must live within herself:

Passions of rain, or moods in falling snow;

Grievings in loneliness, or unsubdued

Elations when the forest blooms; gusty

Emotions on wet roads on autumn nights;

All pleasures and all pains, remembering

The bough of summer and the winter branch.

These are the measures destined for her soul.

3

Jove in the clouds had his inhuman birth.

No mother suckled him, no sweet land gave

Large-mannered motions to his mythy mind.

He moved among us, as a muttering king,

Magnificent, would move among his hinds,

Until our blood, commingling, virginal,

With heaven, brought such requital to desire

The very hinds discerned it, in a star.

Shall our blood fail? Or shall it come to be

The blood of paradise? And shall the earth

Seem all of paradise that we shall know?

The sky will be much friendlier then than now,

A part of labor and a part of pain,

And next in glory to enduring love,

Not this dividing and indifferent blue.

4

She says, "I am content when wakened birds,

Before they fly, test the reality

Of misty fields, by their sweet questionings;

But when the birds are gone, and their warm fields

Return no more, where, then, is paradise?"

There is not any haunt of prophecy,

Nor any old chimera of the grave,

Neither the golden underground, nor isle

Melodious, where spirits gat them home,

Nor visionary south, nor cloudy palm

Remote on heaven's hill, that has endured

As April's green endures; or will endure

Like her remembrance of awakened birds,

Or her desire for June and evening, tipped

By the consummation of the swallow's wings.

5

She says, "But in contentment I still feel

The need of some imperishable bliss."

Death is the mother of beauty; hence from her,

Alone, shall come fulfillment to our dreams

And our desires. Although she strews the leaves

Of sure obliteration on our paths,

The path sick sorrow took, the many paths

Where triumph rang its brassy phrase, or love

Whispered a little out of tenderness,

She makes the willow shiver in the sun

For maidens who were wont to sit and gaze

Upon the grass, relinquished to their feet.

She causes boys to pile new plums and pears

On disregarded plate. The maidens taste

And stray impassioned in the littering leaves.

6

Is there no change of death in paradise?

Does ripe fruit never fall? Or do the boughs

Hang always heavy in that perfect sky,

Unchanging, yet so like our perishing earth,

With rivers like our own that seek for seas

They never find, the same receding shores

That never touch with inarticulate pang?

Why set pear upon those river-banks

Or spice the shores with odors of the plum?

Alas, that they should wear our colors there,

The silken weavings of our afternoons,

And pick the strings of our insipid lutes!

Death is the mother of beauty, mystical,

Within whose burning bosom we devise

Our earthly mothers waiting, sleeplessly.

7

Supple and turbulent, a ring of men

Shall chant in orgy on a summer morn

Their boisterous devotion to the sun,

Not as a god, but as a god might be,

Naked among them, like a savage source.

Their chant shall be a chant of paradise,

Out of their blood, returning to the sky;

And in their chant shall enter, voice by voice,

The windy lake wherein their lord delights,

The trees, like serafin, and echoing hills,

That choir among themselves long afterward.

They shall know well the heavenly fellowship

Of men that perish and of summer morn.

And whence they came and whither they shall go

The dew upon their feet shall manifest.

8

She hears, upon that water without sound,

A voice that cries, "The tomb in

Is not the porch of spirits lingering.

It is the grave of Jesus, where he lay."

We live in an old chaos of the sun,

Or old dependency of day and night,

Or island solitude, unsponsored, free,

Of that wide water, inescapable.

Deer walk upon our mountains, and the quail

Whistle about us their spontaneous cries;

Sweet berries ripen in the wilderness;

And, in the isolation of the sky,

At evening, casual flocks of pigeons make

Ambiguous undulations as they sink,

Downward to darkness, on extended wings.

No comments:

Post a Comment