Upon its premiere, George Stevens’ Giant (1956) was greeted with a resplendent old time Hollywood gala at Grauman’s Chinese Theater. By then, the bitter skepticism that had plagued Edna Ferber’s novel four years earlier had significantly cooled; the premise of the book elevated from minor brutal critique and exploitation of the Texas stereotype to an intimate familial melodrama offset by epic production values and a tempering of the ‘unflattering’ depiction of Texas as a state of big-spending racist blowhards.

To be certain, Ferber’s primary indulgence in the book had been the stripping away of bigotry under the loose disguise of a romance novel. She had based the central character of Jett Rink loosely on Glenn McCarthy; an impoverished rancher who became an overnight millionaire after striking oil. McCarthy’s building of the Shamrock Hotel – a $21 million Houston paradise typified for Ferber the gusty garishness of the entire state. However, upon publication in 1952, the book Giant also ruffled more than a few armadillos west of the Pecos, especially from those Texans whom Ferber had befriended on her travels while writing the novel and who felt bitterly betrayed by her frank exposure.

To be certain, Ferber’s primary indulgence in the book had been the stripping away of bigotry under the loose disguise of a romance novel. She had based the central character of Jett Rink loosely on Glenn McCarthy; an impoverished rancher who became an overnight millionaire after striking oil. McCarthy’s building of the Shamrock Hotel – a $21 million Houston paradise typified for Ferber the gusty garishness of the entire state. However, upon publication in 1952, the book Giant also ruffled more than a few armadillos west of the Pecos, especially from those Texans whom Ferber had befriended on her travels while writing the novel and who felt bitterly betrayed by her frank exposure.“America - rather, the United States - seems to me to be the Jew among the nations,” Ferber commented, “It is resourceful, adaptable, maligned, envied, feared, imposed upon.

It is warm-hearted, over-friendly; quick-witted, lavish, colorful; given to extravagant speech and gestures; its people are travelers and wanderers by nature, moving, shifting, restless; swarming in Fords, in ocean liners; craving entertainment; volatile; the chuckle among the nations of the world.”

Caustic, witty, utterly defiant and oddly charming, Edna Ferber was born in Kalamazoo, Michigan on August 15, 1885. Her talents as a writer on a high school newspaper, the Ryan Clarion so impressed the editor of the Appleton Daily Crescent in Wisconsin that she was put on salary immediately following graduation for the lordly sum of three dollars per week. Anemia sidetracked her ambitions as a newspaper woman, but it also afforded her the time to pen her first short story, The Homely Heroine (published in 1910), and her first novel Dawn O’Hara (1911).

Decidedly not a beauty, Ferber often dressed in more manly attire to mask the fact that she did not possess feminine charms. Indeed, when adroit playwright and wit Noel Coward encountered Ferber wearing a tailored suit he aptly commented, “You look almost like a man,” to which the undaunted and frank Ms. Ferber replied, “So do you.”

A prolific and celebrated novelist, Ferber won the Pulitzer Prize in 1924 for So Big, the first of her novels to incorporate a young woman’s aspirations for a better life. “I think that in order to write really well and convincingly, one must be somewhat poisoned by emotion,” Ferber later wrote in the first of her two autobiographies, “Dislike, displeasure, resentment, faultfinding, imagination, passionate remonstrance, a sense of injustice -- they all make fine fuel.”

Driven by her great moral conscience, such qualities as aforementioned had enticed George Stevens to Ferber’s Giant in the first place. A director of personal conviction, compassion and overall relentless drive to make the sort of films he wanted to, Stevens and Warner Brothers launched Giant on a grand a scale – determined to translate Ferber’s epic saga into an equally thunderous and thoughtful motion picture. At the project’s inception much of the excitement generated by the announcement that Warner Brothers was sending its cast and crew to Marfa Texas for location shooting, chiefly centered on the casting of the film.

Initially Audrey Hepburn and Grace Kelly had been considered for the role of Leslie Lynnton Benedict. Briefly, William Holden was proposed as Bick Benedict. However, Elizabeth Taylor had already starred for George Stevens in A Place in the Sun (1951) a performance that illustrated for the director how sufficiently she had grown up from MGM child star into an actress of considerable charm and substance.

On the eve before production commenced inside the Warner soundstages at Burbank, Elizabeth Taylor graciously invited co-star Rock Hudson and his fiancée for dinner at her, and then husband Michael Wilding’s, home – to get better acquainted. Unfortunately for all concerned, the evening was amply plied with liquor – the net result being that for their first scene together the following morning (Bick and Leslie’s silent falling in love) both actors were considerably hung over.

Remarkable for the time, director George Stevens chose to populate his cast with relative newcomers to the screen and rising stars who were much too young for their parts by the standards set in the novel. Elizabeth Taylor, for example was 23, the same age as James Dean. Rock Hudson was 29. In the film, all would have to credibly age into their early sixties.

The usual transition during this period in film making, for actors involved in generational storytelling, had almost without e

xception been to take a more mature star and reverse the aging process for scenes in which youth was required.

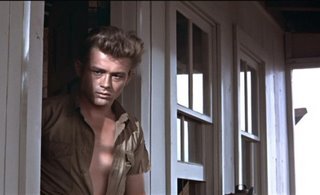

xception been to take a more mature star and reverse the aging process for scenes in which youth was required.Of the three principle leads in Giant, James Dean was initially the most ill at ease with the reversal of this time honored tradition. Unaccustomed to Stevens' improvisation on the set, Dean was equally and chronically dissatisfied by his own singular lack of grasp in playing the aged Jett Rink.

To buttress his insecurities about the part, during a sequence in which Jett slumps off drunk and defiant, Dean turned to Stevens after the scene had already been shot and asked that his performance be removed or edited down as much as possible.

Gradually, the brooding young zeitgeist who had taken Hollywood by storm with electrified performances in East of Eden (1955) and Rebel Without A Cause (1955) came to appreciate both Stevens’ work ethic and his costars – particularly Elizabeth Taylor, whose chic and haughty presence, Dean equated in awe to the glamorous days of ‘old Hollywood’ which he had not been a part of. However, Dean fostered a quiet and unreciprocated resentment toward Rock Hudson throughout the shoot – developing a passive rivalry for Taylor’s affections that ultimately bode well with his character’s looming fascination over Leslie Benedict.

James Dean’s all too brief tenure in Hollywood had begun only a few years prior to Giant with bit parts in Sailor Beware(1952), Fixed Bayonets! (1951) and Has Anybody Seen My Gal?(1952) also starring Rock Hudson. It was director Elia Kazan who chose to gamble on the newcomer’s presence in his production of John Steinbeck's East of Eden (1955). As the wicked and repressed Caleb, Dean captivated and commanded the screen. His image as a dangerous bad boy was further cemented that same year in the role of Jim Stark for Nicholas Ray's Rebel Without a Cause(1955).

Once installed in the remote dessert location of Marfa Texas, Dean generally kept to himself. Save actress Jane Withers – with whom Dean eventually developed a poignant if awkward friendship, and occasional tête-à-têtes with Elizabeth Taylor – accomplished more for the effect of ‘stealing’ Taylor away from the frequent party atmosphere and, more to the point, costar Rock Hudson - Dean immersed himself in the local cattle rancher’s culture to enhance his own performance, even going so far as to learn rope tricks from resident cowboy Monte Hale. Around Marfa, Dean affectionately became accepted as one of the ‘good ol’ boys’ and a resident heartthrob for the local ladies.

In the meantime, the Warner entourage including some thirty trucks of props and prefabricated scenery arrived on the Worth Evans dessert farm that was to serve as the company’s primary location. These props included the towering three-sided façade that effectively became the Benedict ranch house – Riata. An imposing Victorian structure, Riata dominated the barren Marfa landscape.

Daily, cast and crew were besought by two to three hundred spectators on the set, providing an interesting blend of Hollywood dazzle and Texan hospitality. In the evenings, costar Jane Withers offered her own diversions after long intensive days of shooting. Throwing nightly parties that included playing cards and monopoly marathons, these quaint ritual meetings inside the tiny home that George Stevens had rented for the actress provided lighthearted diversionary entertainment that perfectly captured the homespun camaraderie shared by almost all on the set.

Withers’ rental also became the location of a surprise visit. One evening, after everyone else had gone home, Withers was startled to find James Dean reclining on the open sill of her bedroom window. When asked to explain himself, Dean modestly replied that he merely wanted the actress’s attention all for himself. “You come by the front door from now on or you don’t come at all” the actress reportedly told Dean, nailing the window shut to prove her point.

SLOW, SAD GOODBYES

“It's terrible to realize you don't learn how to live until you're ready to die and, then it's too late,” wrote Edna Ferber in her later autobiography; a poignant epitaph that in retrospect rings eerily true for the legacy of James Dean.

Aware of Dean’s underlying restlessness between takes and his overwhelming desire to return to his first love of auto racing, George Stevens had secured a guarantee that Dean would not race or even drive his Porsche Spyder until all of his scenes had been photographed. Honoring that commitment until the last day, James Dean suited up in preparation for a race in Salinas.

In retrospect, the commercial endorsement that Dean shot days before leaving for the Marfa location – in which he urges young driver’s to obey the laws of the road – “…because the life you save might be my own”, has a foreboding and apocalyptic resonance. Yet, perhaps the most poignant and disturbing premonition (if one can believe in such spiritual foreshadowing) came days before Dean’s departure from Marfa.

Costar Earl Holliman recalled a story that Dean regaled him; about encountering a terrible wreck on the highway. A black man lay mortally wounded by the side of the road. To afford this man some shade from the sweltering heat and sun, Dean stood over him for nearly an hour until an ambulance arrived.

But there was no waiting salvation on that lonely stretch of highway outside of Cholame California on the afternoon of September 30, 1955.

While George Stevens and his company were busy reviewing dailies in their projection room, the call, that perhaps no one had expected, came through – James Dean had been killed in a highway collision. The shock and disbelief that resonated throughout the industry immediately following Dean’s untimely demise has since firmly cemented his reputation as a volatile, vital and dangerous rebel. That legacy remains to this very day - forever young in the minds of his adoring fans.

. . .

Far removed from either the dust of Marfa or glittering film premiere in Hollywood that bore at least a fraction of its fame from her enduring legacy, Giant’s author Edna Ferber died of cancer at the age of 82 on April 16, 1968 inside her fashionable Park Avenue apartment.

In a lengthy obituary the New York Times postulated that, “Her books were not profound. But they were vivid and had a sound sociological basis. She was among the best-read novelists in

the nation, and critics of the 1920s and '30s did not hesitate to call her the greatest American woman novelist of her day.”

the nation, and critics of the 1920s and '30s did not hesitate to call her the greatest American woman novelist of her day.”In the forty plus year interim since its debut, George Steven’s production of Giant has maintained Ferber’s earthy façade for robust Texas living. But more than that, Steven’s tender and luminous way with his stars resulted in possibly their best efforts put forth on the screen.

In effect, the film outlives Ferber’s skewed vision of Texas as a culture, a people and a state of mind – though in the final analysis all those ascribed attributes were hers from the beginning. “A closed mind is a dying mind,” Ferber used to say, seemingly oblivious of the narrow frame of reference afforded the characters in her novel.

Ironically, what has been of consequence to historians about the film most recently is mostly its back story and the events leading up to that tragic final hour in the life of James Dean – a star whose fullest potential and longevity would never be realized.

Regardless of the way one interprets the importance of either the author, the novel or the film as it remains today, one truth endures: Giant was a colossus in the making.

@2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment