Elegance, Style and Sexist Machismo in Overdrive

Elegance, Style and Sexist Machismo in Overdrive

In our reconstituted climate of like-minded film fare has James Bond lost his edge?

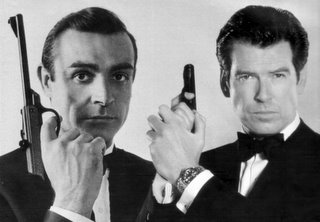

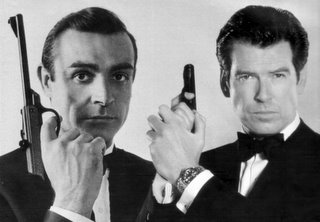

“Bond…James Bond” – even if you have never seen Hollywood’s reconstituted iconography of Ian Fleming’s super Brit (and there are probably at least three people on the planet who have not) there is no denying Bond’s staying power at the box office. In retrospect, varying degrees of accuracy defy pinpointing Bond’s ultimate importance in the cinema firmament. While it is a near mathematical certainty that James Bond has become a universal – the definition behind that universal has ranged from enviable and god-like to parodied masculinity as a misogynist bastard. There would be few among Bond’s critics or admirers adverse to my summation of 007 as an elegant womanizer with hidden talents. Yet, there have been many dissenting opinions on how much farther that assessment could or should be stretched.

Since his cinematic debut in 1962’s

Dr. No much has been written on the women in James Bond’s life: that cavalcade of purring vixens infused with implausible naiveté and infantilized sexual monikers like Pussy Galore or Holly Goodhead. Such have been the fodder for endless feminist discussions and retrospectives on the addlepated and flawed male interpretations of femininity en masse. Particularly from the vantage of today’s thought-numbing and opinion-less political correctness, one has to almost wax apologetically for any remote or fond recollection from that mental snapshot of Ursula Andress rising out of the Jamaican surf.

There is little to dissuade even the most modestly endowed critical thinker from the fact that ‘Bond girls’ have, in large part, been the sacrificial play things, dangled from their bikinis and splayed across the altar of James Bond’s voracious sexual appetite. A Bond girl doesn’t think – she does. What does she do? Well…James. Beyond the voyeuristic ogle of male audience members, content to absorb their lusciousness at a safe distance, and the sometimes modest assist that she provides our hero throughout his perils, the ‘Bond girl’ serves little purpose.

So much for the women. What about Bond’s male influences?

Undeniably, author Ian Lancester Fleming comes first on this list – a debonair Englishman who is arguably the mirror image of his fictional counterpart. In retrospect, Ian Fleming is a character study on how to live life to the fullest. Sharing Bond’s penchant for adventure and beautiful women, Fleming came from good stock. He was the upper-class heir to a distinguished record of heroism put forth by his father in WWI, and augmented by his own, as commander of a squadron in WWII. During the war, Fleming fell in love with the island of Jamaica. After the war it became his home.

Depending on the resource consulted Fleming was either expelled from, or left his prestigious education at Eton ahead of schedule over an ‘incident’ with a girl. The details on this ‘incident’ are sketchy at best but they do point to Fleming’s early precociousness with the ladies – something he would refine as Bondian charisma, both in fiction and in life. Dabbling in journalism and covering spy trials in Russia no less – Fleming eventually penned his first Bond thriller,

Casino Royale, and published it in 1953. In truth, Ian Fleming’s novels had always been a bigger draw in the U.K. than the U.S. – an oversight corrected after President John Kennedy admitted in an interview that he was a devotee of both the author and his fictional hero.

COMING OF AGE IN THE MOVIES

COMING OF AGE IN THE MOVIES

His name was Broccoli – Albert R.: ‘Cubby’ to his family and closest friends - a feisty, committed congenial showman, under whose aegis the name James Bond became an international phenomenon, synonymous with ultra suave sophistication and chic good taste in all things. As a point of fact, Bond and Broccoli shared little in common in temperament. But by all accounts ‘Cubby’ was a man admired by most everyone who met him. He was also not above hunkering down in the mess, even to the extent of cooking a spaghetti dinner for the entire cast and crew when location work proved too remote to have food brought in from a restaurant. It is perhaps a loss to the industry of film making in general that after 1962 the Bond franchise consumed Cubby’s interests in producing films apart from this series.

If any one man should be given credit for molding rough hewn Scot, Sean Connery into that instantly recognizable rake we think of as Bond today, it is more the achievement – or perhaps misadventure, of frequent Bond alumni and director Terence Young. Setting the standard in male machismo with

Dr. No (1962), Young cemented the galvanic cliché of Bond as superhero with

From Russia With Love (1963) and

Thunderball (1965).

The cinematic James Bond is very much a product of his own time. From our current movie vantage he is a text book cliché in masculine esthetics a la the laisse faire fallout of Hugh Hefner, the Rat Pack, and, the overactive wish fulfillment of author, Ian Fleming. Via Jackie Chan, Bruce Willis, Will Smith and their like - who think nothing of devouring the cinematic landscape with a barrage of pyrotechnics - the Bond-ian tradition of expensive cars, hot women, fast living and dangerous adventures is decidedly dated or, at the very least, passé. As a result, the James Bond film franchise has been downgraded from event status to merely one of the many summer offerings where many things are blown up.

For a time, Bond was in vogue. Yet, to appreciate him as an icon one must ignore discrepancies in series continuity; not just the transitions from Connery’s rogue to Lazenby’s stoic goodfella, then Moore’s devil-may-care/anything goes cartoon, and so on but in the very incongruous mortality of the character himself.

Of course, one of the great ironies in film history is that it took a Scotsman to play a Brit. A former pugilist, bodybuilder and jack of most trades, Sean Connery remains Bond in the eyes of many swooning female admirers. To be like Bond became more than an aspiration; it was a national past time. Britain’s most revered agent was not merely wallowing in contemporary chic. He was trend setting and shaping it into an iconoclastic bit of fluff and nonsense that has since long outlived, or perhaps, overstayed its testosterone driven balderdash.

Yet, in the shadow of radical feminism, with our kinder/gentler more woman identifying and sensitive counterculture to Bond’s sexist reliquary, there doesn’t seem to be much left for 007 to do, but retire his Walther PPK and subscribe to some vintage cable porn for kicks. With the release of

Dr. No in 1961 came the end of innocence for fans of Ian Fleming and the birth of Bond-philes.

The hero was now the property of a Hollywood studio. Modesty and toughness alone simply would not do. Budgets doubled with each consecutive installment and, with them, the expectation that James Bond was not only getting bigger, but better. 1964’s Goldfinger, with its emphasis on a gadget-laden Aston Martin DB5 and Honore Blackman as femme fatale, Pussy Galore, elevated James Bond to super human and ensured his place in the cinema firmament. But it also buried the character, and any actor who portrayed him, beneath a crumbling artifice of ignoble sexuality.

Despite the glamorous, if infantilized, moniker ‘ Bond girls’ that yielded the vapid byline, ‘don’t sweat, they just glow,’ the women of 007’s world do very little else throughout the series; the underlying premise of sultry, if slightly stupid holding out to Bond’s own agenda for unquantifiable sexual gratification so long as the heart and genitals hold out.

If nothing else, the hiccups in the timeline, illustrated by the brief tenures of George Lazenby and Timothy Dalton in the title role, symbolize Bond’s increasingly limited hold on an audience. Bond is no longer king of his cinematic domain, more like a loyal subservient to that 24 kt. cage of faux insolence that film history has constructed for him.

The world surrounding 007 has changed and not in such a way to allow any mutation of Bond as a better fit. Instead, the character, and those who may dare to play him in the future, might have to resort to retrofitting further adventures in a time capsule; a sort of James Bond – the forgotten years. Only then does the fantasy of this gun-toting Rico Suave seem to generate pale ghosts in the vein of Bond’s once galvanic staying power at the box office. Otherwise and realistically, by now James Bond should be confined to a stretcher with crippling arthritis and semi annual trips to the free clinic.

THE FILMIC 007 – a retrospective of the movies

It was a 60 million dollar mega hit upon its general release in 1962 – a success by most artistic and all box office standards. Today however,

Dr. No appears more the quaint relic of sixties pastiche than the foray into cutting edge film-making that it was. In truth, the movie that introduced Ian Fleming's James Bond to American audiences was fraught with preproduction difficulties, not the least of which was the proposed budget did not match the epic quality that Albert R. Broccoli and his partner, Harry Saltzman had envisioned.

Prior to obtaining the go-ahead from United Artists, neither producer could find a studio willing to commit to their project. To secure their own position within the franchise, Broccoli and Saltzman wisely co-founded EON Productions. Although Saltzman would periodically tire of both Bond and his partner – producing films away from the franchise with considerable speed and popularity – for Broccoli, the focus ultimately became one of keeping his most lucrative investment fresh and growing. Neither Bond nor the movies would ever be the same again.

Director Terence Young must be credited for molding Sean Connery into 007. However, it was visionary film and animation pioneer, Walt Disney who first discovered the Scottish born actor. A former bodybuilder and virtual unknown in films, Connery garnered considerable praise and industry attention after appearing in Disney’s

Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959).

In

Dr. No, his first outing as Britain’s most amiable super spy, Connery managed to cut a dramatic swath and imbue the character with his own iconography, almost from the moment he stepped before the camera and uttered the tagline,

“Bond, James Bond.” Connery relished the role but he quickly developed a natural dislike for the mob-mentality that made him a groupie magnet around the world. His later career would be spent making futile attempts to escape the pigeon-hole popularity he had helped to create.

To those weaned on contemporary Bond adventures, the plot of

Dr. No is tame. Bond is sent to Jamaica to investigate the murder of a British covert operator. He is first threatened then kidnapped by the formidably dangerous, Dr. No (Joseph Wise), an Oriental mastermind with no hands, who has developed a radar toppling system directed against American missiles launched from Nassau.

The formula of latter day Bond films is understandably absent here, with a refreshing lack of high tech gadgetry and special effects. As Honey Ryder – the girl that set the trend for all subsequent ‘Bond girls’, Ursula Andreas cut a handsome figure in her white bikini, an indelible image that

Die Another Day (2000) attempted to recreate with actress Holly Berry.

After rising from the surf in search of sea shells, Ryder is startled by Bond’s presence on the beach. She innocently asks

“Are you looking for shells?” “No,” says Bond,

“I’m just looking.” This overt sexuality and the aggressiveness infused by Connery into the role, led to condemnation by the Vatican – a move which helped generate public interest and transform the modestly budgeted thriller into a

$60 million dollar super hit.

As President Kennedy had previously made it known that

From Russia With Love (1963) was his favorite Bond adventure it seemed only natural as the follow-up to

Dr. No. In point of fact, Broccoli and Saltzman would have preferred

From Russia With Love as Bond’s entrée into cinema. However, its weighty plot and shifting locales were prohibitive to the budget they had been allotted by United Artists. At the behest of the studio Broccoli and Saltzman agreed to change the name of Bond’s arch nemesis from SMERSH, a Russian based espionage ring, to SPECTRE an independent underworld organization, thereby diffusing whatever Cold War animosities the film might have otherwise incurred.

However, although

From Russian With Love has some marvelous vignettes, the best of these being the two lavishly staged fight sequences; the first in a gypsy camp, the latter between Bond and SPECTRE assassin, Red Grant (Robert Shaw), as a whole the film seems far more dated and problematic than either its forerunner or subsequent adventure, Goldfinger. The helicopter assault sequence, as example, in which Bond is attacked from the air as he races across the stark hillside, is decidedly a ripped off homage to Hitchcock’s penultimate wrong man classic,

North by Northwest (1959), in which Cary Grant is similarly besought by rapid fire from a biplane. So too, does the initial set up of Bond seem out of place with a rather lengthy prologue that takes much too long to make its point.

With a budget twice that of its predecessor,

From Russia With Love began its shoot as an expensive project destined to be promoted as more ‘an event’ than a movie. But spirits on the set were dampened when actor Pedro Armendariz (cast as MI6 secret agent Kerim Bey) was diagnosed with a fatal form of cancer. Working around Armendariz’s condition – and eventually restructuring the schedule to accommodate his deteriorating condition the pall of his death before completion of the rest of the story elements, seems to have impacted the mood of the story as a whole.

From Russia With Love

From Russia With Love remains a somber entrée in the Bond franchise – darker, more sinister and ultimately less effective than

Dr. No. Even Connery appears ill at ease as he strikes Russian defector Tatiana Romanova (Daniela Bianchi), a woman he has just finished making love to, in an attempt to gain a confession into what she in fact does not know – that her superior officer, Rosa Klebb is a defector currently employed by SPECTRE. At $78 million in worldwide box office returns, From Russia With Love was a valiant financial successor to

Dr. No – yet, like James Cameron’s

Titanic, it is only in revenue perhaps that the film should ultimately be considered a great success.

Although it ranks as number three in chronology,

Goldfinger (1964) is arguably the most perfectly realized of the early Bond adventures and without question, its’ most popular. A grandly amusing compendium of implausible gadgetry, death-defying stunts and sultry women with absurdly sexualized names, it can be effectively stated that the cinematic Bond had his first and final departure with Fleming’s original conception on this occasion. After a pre-title sequence that has Bond blowing up a heroin manufacturing plant in Cuba, before electrocuting a would-be assassin in his bathtub, the real story of pursuing billionaire, Auric Goldfinger (Gert Frobe) begins.

Determined, perhaps not to repeat the atmospheric noir feel on

From Russia With Love, director Guy Hamilton lightens the mood where ever and whenever a break in the adventure occurs. Auric Goldfinger’s above board trading and business practices are merely a front for a rabid fascination to monopolize the world market on gold reserves. To this end, Goldfinger employs flight instructor, Pussy Galore (Honor Blackman, as the most inspired choice for the ultimate Bond girl) to train a troupe of like-minded female pilots. Their job; fly over Fort Knox and disperse a highly lethal nerve gas on the surrounding military bases so that Goldfinger can detonate his nuclear device inside its vaults, thereby rendering the gold radioactive for hundreds of years to come.

What is particularly appealing about the film today is its inventive sets by art director Ken Adams– including Goldfinger’s laser beam laboratory (in which Bond’s captured livelihood is almost cut in two), the rumpus room on Goldfinger’s stud ranch (with its moving floors, shifting furniture and sliding door and window panels), and the impressively massive fantasy interpretation of Fort Knox, complete with functioning elevators and endless rows of bullion, improbably stacked several stories high from floor to ceiling.

Ultimately, these locations are larger than life hence the stature of Bond and his villain are elevated to near mythical proportions. The stage for all of the impressive grandeur that follows is defined early, when Goldfinger’s bikini-clad con artist, Jill Masterson (Shirley Eaton) is murdered in Bond’s bedroom by mute henchman, Oddjob (Harold Sakata); her nude body dipped in gold paint and spread out as a macabre warning.

Throughout the film, various modes of death have been cleverly devised: from Oddjob’s decapitating bowler brim – which is demonstrated effectively twice (first; lopping the head off a cement statue at a country club, then later; slicing through the neck of fleeing victim Tilly Masterson - Tania Mallet) to the crushing of Mr. Solo (Martin Benson) into the dimensions of a nine by eleven cube inside a compactor – the film’s flippant approach to murder is both enthrallingly diabolical and marvelously tongue-in-cheek.

Arguably, the film is most effective in its playful badinage between Bond and vivaciously feline, Pussy Galore (Honor Blackman). When first coming into focus from a drugged stupor, Bond understandably asks, “Who are you?” “I am Pussy Galore,” Blackman defiantly declares. “I must be dreaming,” is Bond’s only reply.

Indeed, all of the elements in

Goldfinger function idyllically like a sublime – if slightly perverse – dream, steeped in male machismo. Bond is no longer human, but superhuman; his scope and relation to the world of espionage forever removed from the mundane truths of the profession, as perhaps best exemplified on film by Martin Ritt’s

The Spy Who Came In From The Cold (1965). On all accounts then,

Goldfinger is a 24kt hit.

Financially speaking,

Goldfinger tipped the scales with a meteoric return on its investment: $125 million worldwide – a record in the Guinness Book. Anyone questioning Bond’s staying power as a cinematic icon for the postwar age need only have asked Sean Connery about the obsessed female fan who threw herself into the open window of the film’s Aston Martin as he drove it to the world premiere. With

Goldfinger James Bond left the limited appeal of Ian Fleming’s creation behind in favor of becoming an international phenomenon.

Goldfinger’s resounding critical and financial success did come with one adverse repercussion. It forced producers Broccoli and Saltzman into an impossible upward swing. From this point onward, Bond had to commit to topping himself in each subsequent adventure – often with mixed reviews, a sacrifice in character development and almost entirely with an increasing emphasis on stunt work as opposed to style. These forfeits to the integrity of remaining true to Fleming’s roots first became apparent in the next Bond film,

Thunderball (1965) – a $5.6 million dollar epic shot for the first time in the expansive, though problematic, aspect ratio of 2:35.1 Panavision.

Former collaborators Kevin McClory and Jack Whittingham created a minor sensation even before production on Thunderball began by suing Ian Fleming during the publication of his novel. They claimed that Fleming had lifted whole portions of his story from a manuscript they had written but were unsuccessful at marketing to prospective film producers. Settled out of court, the suit nevertheless attached the very real prospect of McClory trading on Bond’s popularity and selling his option to a rival film company with like-minded themes to those in Thunderball. It would have been so easily accomplishable. By 1965, Bond had spawned a host of imitators; from the cinematic incarnations of Matt Helm and Derek Flynt to television serials like

I Spy and

The Wild Wild West. In order to diffuse the situation, Broccoli and Saltzman agreed to a truce, whereby they relinquished producer credit on

Thunderball to McClory.

As an artifact of the mid-1960s,

Thunderball is perhaps no more resplendent or lengthy a film than most of the period. The manic quest to develop properties deriving more style than substance (spawned by 1954’s induction of Cinemascope) had reached a level of saturation in properties almost entirely dependent on widescreen for their box office draw. By 1965, even stories that arguably would have functioned better on a more succinct budget and smaller scale were erroneously blown out of proportion.

However, as a Bond adventure,

Thunderball does tend to lag, particularly during its underwater sequences – the most ambitious undertaken for any film to that date. During production, director Terence Young had expressed as much concern over the film’s running time – nearly two and a half hours. Regardless,

Thunderball premiered at that length and almost overnight became the sort of sensation few blockbusters before or since can lay claim to. Impressively weighing in its worldwide revenue at $141 million – in terms of the number of paid admissions,

Thunderball breaks many records set by more contemporary blockbusters.

The resiliency of

Thunderball (it managed to play on a twenty-four hour bill at New York’s Paramount Theater for nearly a year) in retrospect cemented the fate of

You Only Live Twice (1967): a grossly over-inflated super production mimicking the public’s then current fascination with the fanciful space age. The screenplay by Roald Dahl jettisoned all but two aspects of the Fleming novel and instead concentrated on being more lavish, and action/gadget laden then its predecessor. However, for the first time since stepping into the shoes of Britain’s most amiable spy, Sean Connery was expressing an interest to retire from the role. Perhaps exhausted by the public’s adulation and aware that he was aging beyond the public’s conception of the younger man about town, Connery announced that

You Only Live Twice would be his last outing as 007.

The story unfolds with the assassination of Bond – a fake, designed to throw Bond’s old arch nemesis Blofeld off his trail. In the meantime, American/Russian space launches have been paralyzed by a series of inexplicable disappearances of their rockets while in orbit around the earth. Naturally, both sides assume that the other is responsible for these disappearances. Suspecting SPECTRE behind the rouse, Bond travels to the Far East where he discovers a launching pad inside a fake crater of a dormant volcano.

You Only Live Twice

You Only Live Twice is a lengthy excursion, but one absent of

Thunderball’s unique blend of glib comedy and action. So too are the ‘Bond girls’ on this outing problematic. Aki (Akiko Wakabayashi) is amiable and engaging enough – but she is killed off before the final reel, during a botched assassination attempt on Bond’s life. Kissy Suzuki (Mie Hama) represents reproachable virginity – an admirable quality that is perhaps ill-tailored for the Bond franchise. Helga Brandt (Karin Dor) is the evil femme fatale – uncharacteristically hard-edged, then equally unconvincing as she softens to Bond’s charms and shortly thereafter dumped into a pool of piranhas.

One aspect of the film remains galvanic and entertaining: its penultimate action sequence inside the volcano’s crater. Framed inside Ken Adam’s outrageously elephantine set, the stunts are harrowing; the camera work by Freddie Young stunning and strangely poetic. Even the pacing delivered by director Lewis Gilbert excels in a way that the rest of the film generally tends to fall flat on. Budgeted at $9.5 million, the film was a success, even though its worldwide gross of $111 million tended to pale in comparison to

Thunderball’s record-breaking tally.

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969) represents something of both a departure and a finale for the series. At 140 minutes it is the longest Bond adventure. It is also the last of the breed imbued with that stylish kitsch in ultra-60s chic. Producers Cubby Broccolli and Harry Saltzman had done their best to woo their bankable star into the fold but to no avail. Presented with the daunting task of ‘discovering’ the next James Bond the producers eventually settled on fashion model, George Lazenby who had yet to add film work to his list of professional credentials.

Concerns that Lazenby would be a jolt to audience expectations, and possibly be the series’ final act, trailers and poster art featured a faceless Bond as part of their marketing campaign. Yet, what is most often forgotten in retrospectives is that the film is probably the single most detailed and fully realized Bond in the entire series. It treats the character not as the cardboard cutout of a superman (which he had rapidly deteriorated into during Connery’s tenure) but genuine flesh and blood with very real emotional needs for love and to be loved.

From the onset, director Peter Hunt builds a carefully constructed mélange, determined not to replicate or even mimic Connery’s iconography, but rather allow Lazenby to discover Bond through his own characterization. The pre-credit sequence features a fight done mostly in silhouette, at the end of which Lazenby’s face emerges in his first close up and with the glib comeback, “this never happened to the other fella.” The line – deserving of a round of applause at the premiere, was actually a throw away that Lazenby had been using around the set.

What is also unique about

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service is Bond’s unmistakable passion for his Bond girl – Tracy Vincenzo (Dianna Rigg). In a series populated by buxom bimbos and fiery femme fatales, Tracy represents the Bond ‘girl’ as a complete woman. Her fears and anxieties, her self-destructive nature, mirror Lazenby’s conflicted performance as Bond – they are counterparts cut from the same cloth. While previous, and for that matter subsequent, Bond adventures have set up the very cold and removed premise that women are a means for fleeting sexual gratification or at the very least, diversionary eye candy, the characterization of Tracy brings out the very best in Fleming’s hero. He is genuinely moved by her, rather than merely going through the motions to satisfy his own, and for that matter, the audiences’ expectations.

The plot diverges into two very different narratives; the first, a traditional Bond, the other a rare opportunity to present James as a man first, agent second. In an entanglement reminiscent of Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew, Bond is assigned the task of wooing sexually frigid Contessa Teresa ‘Tracy’ Vincenzo by her father; shipping magnet, Marc Ange Draco (Gabrielle Ferzetti). Although Bond and Tracy’s initial meeting is disdainful – the eventual romance that blossoms between them is quite genuine. But before Bond can pop the question, duty calls. He is sent to impersonate Sir Hilary Bray a genealogist scheduled to inspect the coat of arms of a respected personage atop a mountain retreat. Instead, what Bond finds is that his old arch nemesis, Ernes Stavro Blofeld (on this occasion cast as Telly Savalas) is plotting a toxic game of mind control, using a bevy of neurotic lovelies as his hypnotized harbingers of doom.

Director Peter Hunt must be given credit for producing this textually dense – though never boring - film as seamless blend of all these narratives threads. The action sequences are masterful set pieces that rank among the best in the series – including a toboggan/ski run chase, and, an auto race that ends only after Bond and Tracy have entered a legitimate motocross.

What seems to be the sticking point for most audiences today is that neither Connery nor Bond’s other iconic performer, Roger Moore are on hand for the proceedings. As Bond, George Lazenby is decidedly more wooden than Connery, and yet removed from Connery’s hype and Moore’s savvy way around a one liner – Lazenby is quite adequate in the role. His emotional response to Tracy’s murder is a highpoint for the film that neither Connery nor Moore ever achieve. But there is no denying that in keeping with the history of Bond as a character, Lazenby is something of a road show distillation, instead of iconic and galvanic in the part himself. When all was said and done,

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service proved to be a considerable success at the box office, raking in $80 million.

Yet, it was a comparative disappointment to previous receipts on

Thunderball and

You Only Live Twice. Lazenby, who had performed admirably on camera - though arguably less than on the set (rumors have persisted that he was a bit of a Prima Donna) - was officially ousted after his agent demanded an undisclosed sum for the next Bond. Whatever the price, it proved too high for Broccoli and Saltzman to seriously consider. Hence, Lazenby was out and Connery reluctantly returned for the next Bond outing,

Diamonds Are Forever (1971).

The return of Connery was only partly philanthropic. The actor’s films outside of the franchise and during his absence from it had proved dismal, both artistically and financially. Further to the point, Connery had recently become involved in setting up the Scottish International Educational Trust. Receiving a then unheard of sum $1,250,000 for his return to the franchise – plus a percentage of the film’s gross – these profits were donated by Connery to that charity.

Instructed to ‘update’ Bond for contemporary American sensibilities, director Guy Hamilton’s

Diamonds Are Forever is perhaps the most deglamorized of the vintage films. A downscaled, upbeat and remarkably adroit and adrenaline-infused romp through Las Vegas, the film is remarkably un-Bond-like in both its look and feel.

The story begins in earnest with a South African diamond smuggling ring. Not up to Bond’s usual assignments, even though everyone associated with the sparkling gems turns up dead, Bond kills the next link in the chain, Peter Franks (Joe Robinson) and assumes his identity. He quickly discovers that his old nemesis, Blofeld (on this occasion played by Charles Gray) has taken over the bachelor pad of a reclusive Las Vegas millionaire, Willard Whyte (sausage king, Jimmy Dean in a loose Texas parody of Howard Hughes).

On reflection, the best thing about

Diamonds Are Forever is its no-nonsense Bond girl, Tiffany Case (Jill St. John), who represents a definite shift in the parameters of the ‘Bond girl’ from sultry plaything to fast thinking, sharp-shooting accomplice. In hindsight, the most damaging characterizations in the film are that of Mr. Kidd (Putter Smith) and Mr. Wynt (Bruce Glover) a pair of homosexual tongue-in-cheek assassins – miserably coy and painfully out of touch with either previous Bond villains or more contemporary tastes in political correctness.

The rest of the plot and staging is par for the course of a

Smoky and the Bandit rather than vintage Bond panache. Starlet Lana Wood appears in a brief but memorable cameo as crap shooter, Plenty O’Toole – “named after (her) father, no doubt”, while Trina Park and Lola Lawson performed as a pair of acrobatic assassins, Bambi and Thumper: easily foiled by Bond in the reflecting pool adjacent Whyte’s desert home. Despite the lack of production values that had indelibly etched the previous Bond adventures into the public’s fascination, upon its release,

Diamonds Are Forever proved a winner with the most successful seven day gross in the history of British cinema and the largest opening weekend in the United States: $116 million all told.

The concern for Broccoli and Saltzman in the spring of 1973 was in replacing Connery once and for all with another actor to carry on the series. Set against the daunting prospect of choosing a virtual unknown – as they had done with Lazenby – the producers eventually settled on Roger Moore whose previous acting credentials had included a stint opposite Elizabeth Taylor in

The Last Time I Saw Paris, and his lead as Simon Templer in the popular intercontinental television serial,

The Saint.

In retrospect it seems impossible to consider any other actor accepting the mantle of super spy-dom. But in 1973, Moore was on equal footing for consideration with actor Timothy Dalton. Although flattered at having been chosen, it was Dalton who declined the offer first, deeming himself much too young to play the seasoned British agent.

With

Live and Let Die (1973) Roger Moore realigned the persona of 007 with more contemporary trends – no small feat of accomplishment, considering how rabidly popular Connery’s stoic and brooding Bond had been only a few short years before. Yet, unlike Connery – who had detested the glitz, glam and endless hounding for autographs and interviews from the press and his fans, almost from the moment he had essayed into the role– Moore relished every moment in the process of becoming Bond and proved to be a great raconteur, both on and off the set. While filming in the tropics, Moore also attended a Tarot ‘reading’ of his future that uncannily predicted with accuracy he would have a son and become a humanitarian for UNICEF.

Redesigning Bond to suit Moore’s personality meant the loss of the harder edge that Connery had infused into the character. As screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz would later explain, Connery’s personality allowed for the option of writing a scene in which Bond either kissed or killed a girl. Moore, however, would appear thuggish and ill at ease with this latter option. Hence,

Live and Let Die has plenty of threatening menace – but most of it is delivered by Moore as total quip and tongue-in-cheek.

Ironically, at the time of the film’s release, critics perceived this nonchalance as having a ‘softening’ effect on the character of Bond. They also criticized the inclusion of J.W. Pepper (Clifton James), a sublimely over-the-top caricature of the Southern bigot that nevertheless won the laughs and popularity of audiences. If any singular unforgivable sin may be ascribed to

Live and Let Die it derives from the absence of resident gadget master “Q” (Desmond Llewelyn); an omission that has never been satisfactorily explained.

Today,

Live and Let Die more heavily dates than most of the Bonds – certainly more than any of the other Roger Moore classics. Its focus on Harlem hoods, thugs and a drug cartel run by San Monique politician Dr. Kananga/Mr. Big (Yaphet Kotto) simply reeks of the sort of blacksploitation that readily flooded the marketplace then, but is now acknowledged and almost universally panned as racial tripe in films like

Shaft (1971),

Blacula (1972) or

Foxy Brown (1974).

The heady concern that Moore would not be accepted as Bond by his peers was counterbalanced by an impressive media blitz in publicity that included everything from a round of interviews to oddities like commercial tie-ins with Evinrude Motors and Glastron Boats, and even a commercial in which Moore trades vodka martinis to promote milk consumption. The campaign proved successful. Upon its release,

Live and Let Die became the most profitable Bond yet, raking in $161 million. Broccoli, Saltzman and Moore could at last breathe a sign of relief.

With

The Man With The Golden Gun (1974) Roger Moore’s tenure in the series was secured – if tentatively, by an absurdly comedic entrée that threatened to push Bond into the realm of extreme slapstick. After receiving a golden bullet marked with his double-o insignia, Bond is relieved of all duties and asked by his superior, M (Bernard Lee) to disappear for a while. Instead, Bond plots to stake out Francisco Scaramanga (Christopher Lee) – the man with the golden gun. Unbeknownst to Bond, Scaramanga doesn’t really want him dead. The bullet was actually sent by the hit man’s girlfriend, Andrea Anders (Maude Adams, in her first appearance in a Bond movie). Unfortunately, Bond realizes that Scaramanga’s intentions are to annihilate the world through the harnessing of a destructive solar device built on a remote island in Red China seas.

Though many critics consider the film a garish hiccup: too coy to be taken seriously and too extreme to be believable, in retrospect

The Man With The Golden Gun seems to foreshadow other pending Bond mega hits, like

Moonraker (1979) and

Octopussy (1983). And then, of course there is Christopher Lee. As Scaramanga, Lee is perhaps the second greatest Bond nemesis to ever appear in the franchise, sandwiched between Auric Goldfinger and Hugo Drax.

Justly famous too are the several fantastic set pieces in action, including a three-sixty mid-air roll stunt over open water, two funhouse sequences, and, the climactic showdown on Scaramanga’s island, in which a miniature model of the doomsday device - appearing remarkably convincing even under today’s scrutiny in special effects – is destroyed in a glittering ball of flame. Also noteworthy is pint size Bond villain, Nick Nack (Herve Villechaize, of Tattoo fame on television’s Fantasy Island).

However, in Bond girl Mary Goodnight (Britt Ekland), a vapid flaxen-haired bubblehead the film has an insurmountable obstacle. In every way, Goodnight is the female equivalent of a village idiot – placing herself in one precarious circumstance after the next and becoming completely ineffectual as a woman to whom Bond would ever consider sharing his bed, let alone his adventures.

Tepid box office response to

The Man With The Golden Gun (it only grossed $98 million) presented Broccoli and Saltzman with the very real prospect that this would be the last Bond adventure. For Saltzman, the prophecy came true. Forced into personal debt that threatened to bankrupt EON Productions, Broccoli had no choice but to dissolve their partnership in order to save his company from financial ruin.

Arguably then, one of the worst Bond films was followed by one of the very best,

The Spy Who Loved Me (1977); an action-packed thriller that returned the franchise to its epically mounted roots and infused Moore’s tenure with new resilience. Determined to prove his harshest critics wrong, Broccoli invested $13.5 million in bringing the story to the screen. The investment included the return of production designer Ken Adams and construction of the now famous 007 sound stage at Pinewood Studios – a gargantuan building that eventually housed the interior of the Liparus ocean tanker and mock ups of three full scale submarines. In every way then,

The Spy Who Loved Me was envisioned as larger than life – a moniker well deserved upon the film’s galvanic premiere.

Another minor bru-ha with screenwriter Kevin McClory prevented Broccoli from reviving the organization of SPECTRE as part of his narrative. Instead, Britain’s most amiable super spy was pitted against billionaire oceanographer, Strombold (Curd Jurgen) in a death-defying race against time to save the earth from total nuclear destruction. Strombold is obsessed with building a totalitarian empire beneath the sea.

Ken Adams eventually settled on very smooth rounded lines for most of his designs, including the ominous Atlantis, a laboratory capable of rising and sinking into the sea. The amphibious Lotus Espirit – another gadget laden mode of transportation for 007, that seemed over the top in its time, has since become a reality of our modern times. But perhaps the film’s most enduring creation came in the personage of Bond villain Jaws; the towering ogre with stainless steel teeth who bites his victims to death, played by Richard Kiel.

Finally, Moore’s tongue-in-cheek way with a one-liner that had seemed perhaps too deliberate in his previous efforts was brought into check and justified with the character of James Bond. When Bond and Triple X are discovered by their superiors, making love in a very public venue, M (Bernard Lee) blurts out,

“Bond, what the hell are you doing?” to which Moore fittingly replies in his usual nonplussed demeanor,

“Why, keeping the British end up, sir!”

Launched under a revised distribution policy by United Artists,

The Spy Who Loved Me went on to gross $185 million worldwide, a colossal blockbuster by most accounts, made all the more impressive when one considers that the film opened just weeks after George Lucas’ groundbreaking

Star Wars. Critically too, this latest Bond garnered high praise, understandably for its impressive sets and what can only be considered James Bond’s return to form. Even those cynics in doubt prior to the film’s release were ultimately left conceding that in terms of high adventure, when it came to 007 – nobody did it better.

Moonraker

Moonraker (1979) is perhaps the most lavish and bizarre of the James Bond adventures. In capitalizing on the obsession with the space program the screenplay by Christopher Wood retained only threadbare elements from the Fleming novel in which a megalomaniac industrialist, Hugo Drax (Michael Lonsdale) hijacks his own shuttle for an outer space rendezvous with a secret space station. In an age of intergalactic pipe dreams – this one must have seemed like an implausible lulu, though the Russian space laboratory - MIR has since afforded at least part of Drax’s dream a curious legitimacy.

After the stunning ovation he received in

The Spy Who Loved Me Richard Kiel reluctantly agreed to reprise his role as Jaws in

Moonraker. In truth, Kiel did not mind the part so much as he detested the awkward metal fangs he was forced to wear. The stainless steel could only be inserted into his mouth for short periods because it made him gag.

Determined that every penny should show on the screen, Broccoli moved his production from England to France in order to escape the oppressive British tax laws – consuming its two studios; Éclair in Paris and Studio de Boulogne in Epinay with Ken Adam’s extravagant sets – the largest ever built at either studio. But Pinewood remained Bond’s home for Derek Meddings’ impressive array of special effects which earned him and the film its’ only Oscar nomination and win.

Although

Moonraker had, and continues to have, its list of detractors, Christopher Wood’s screenplay is, for the most part, an exercise in total fusion of all of the elements that have made previous Bond films such an unqualified success: bold original stunt work and marvelously integrated action sequences, a diabolically effective villain (Michael Lonsdale), a peppering of light humor a la Moore, and an engaging Bond girl in Holly Goodhead (Lois Chiles).

As Bond becomes determined to rid the world of another obsessive madman, the production globe trots from Rio to Argentina to outer space with impressively nimble speed that never once seems contrived or out of place. As far fetched as fantasy goes -

Moonraker delivered on every level, its’ $203 million worldwide gross an unsurpassed fiscal achievement for the franchise until 1995’s

Goldeneye.

Although

Moonraker had been financially successful, producer Broccoli had shared the concern and sentiment echoed by die-hard fans, who found its lack of reverence for the serious side of Bond appalling. Hence, with

For Your Eyes Only (1981) Broccoli made every attempt to return Bond to his more ‘realistic’ Ian Fleming based roots. In everything from the film’s opening sequence (that has Bond placing flowers on the grave of his late wife, Tracy) to the staging of its action sequences, (right up to and including the climactic near drowning of James and his Bond girl, Melina Havelok (Carole Bouquet), there is a sense that the events occurring in this film, above all other Bonds, are quite plausible. The fact that Bond does not save the world but merely aids in the preservation of its currency, in retrospect foreshadows the present downgrading in Bond’s status from super human, to just an action guy with really cool gadgets.

Bond is deployed to recover a decoding device from a British sea vessel, the St. Georges, that has sunk somewhere off the coast of Greece. At the same time, Melina Havelok (Carole Bouquet) is on a mission to avenge the murders of her mother and father who were attempting to salvage the wreck. Inevitably these two destinies collide when it is discovered that a man named Aris Kristatos (Julian Glover) is responsible for both the sinking and the killings. At first, Kristatos presents himself as an ally to Bond. He is a cultured patron of the arts and devoted sponsor to Olympic hopeful, Bibi Dahl (Lynn-Holly Johnson in a camp performance as an underaged/oversexed skater, setting her cap for Bond, and Kristatos stooge, Erich Kriegler – John Wyman). However, very shortly these alliances shift as Bond discovers his true compatriot in Greek smuggler, Milos Columbo (Topol).

In retrospect, this film is notable for the appearance of the late first wife of future Bond, Pierce Brosnon; Cassandra Harris as the Countess Lisl. Esthetically,

For Your Eyes Only also marks a first for Bond films by featuring the transparent ghost of Sheena Easton singing against the main title sequence. At $195 million, the receipts on

For Your Eyes Only may not have been as impressive as those accumulated by Moonraker, but they were respectable enough to convince Broccoli that his revised interpretation of Bond had been the correct one all along.

Octopussy

Octopussy (1983) is one of the best of the latter day Bonds. Certainly, the film must rank as a high water mark in Roger Moore’s tenure. Far more complex than most, the film is a potpourri or perhaps more accurately stated penultimate compendium of the essentials that best quantify the franchise. On this occasion, 007 is assigned to investigate the curious appearance of a Faberge Easter egg at a Sotherby’s auction, marked ‘property of a lady.’ What he discovers is that the lady, Magda (Kristina Wayborn) is the property of one, Kamal Khan (Louis Jourdan), a prince of spurious heritage who is using the backdrop of his fabulously wealthy lifestyle to hide a diabolical agenda. Khan plans to detonate a nuclear bomb on an American military base in Germany with the complicity of a Russian dissident, Gen. Orlov (Steven Berkoff). The act of terrorism will surely bring about WWIII. However, beneath this lofty and maniacal ambition is Khan’s base deception to steal the Romanoff royal jewels.

Enter Octopussy (Maude Adams in her second appearance in a Bond film; the first was in The Man With The Golden Gun); a business woman whose traveling circus is populated by a motley crew of lethal femme fatales. Both she and her staff have pledged allegiance to Khan under the false pretense that they are working as a team. However, when Octopussy learns that she has been used as a pawn, and furthermore, that Khan planned to do away with her in that same nuclear explosion, she takes her place on the side or righteousness and becomes Bond’s ally.

Buttressed by masterful set pieces and stunning locations,

Octopussy was released at the same time as a rival Bond picture

Never Say Never Again: a thinly disguised and badly updated remake of

Thunderball, starring Sean Connery. In every way,

Octopussy outranked this latter entrée and tied Moore’s appearances in Bond movies with the Connery legacy. A year later, Moore would top his tally with his final Bond flick,

A View To A Kill (1985).

Much maligned upon its release,

A View To A Kill effectively rounds out Roger Moore’s tenure in a flurry of classic clichés and stunning action sequences. It also marks the retirement of Bond alumni Lois Maxwell in the role of Miss Moneypenny – Bond’s long suffering unrequited, yet ever hopeful, love interest.

What is perhaps most regrettable is the film’s attempt to not so finely balance camp elements (as with Bond, knocking the hats of a couple of cowboys while clinging to the undercarriage of a fire truck ladder) with the more serious brevity of saving the world yet again. Bond alumni, John Glen directs with his usual flair for the spectacular; and to be sure, during both the Eiffel Tower jumper stunt and the climactic Golden Gate Bridge battle of wills between Bond and villain Max Zorin (Christopher Walken) he does manage to recapture the thrill and excitement that exemplifies the very best of the series. Although not nearly as bad as critics tend to misrepresent it, A View To A Kill does tend to fall somewhat short of expectations – most notably with the casting of Tanya Roberts as Stacey Sutton – an ineffectual and all together incompetent heroine, very much reminiscent of Mary Goodnight in The Man With The Golden Gun.

Bond is assigned to investigate Zorin, a leading industrialist who is using steroids to win horse races. Zorin’s accomplices are a former practicing Nazi, Dr. Carl Mortner (Willoughby Gray) and a devious woman of means and menace, May Day (Grace Jones). What Bond discovers is that Zorin plans to flood Silicon Valley by generating a cataclysmic earthquake with the detonation of a nuclear device beneath the earth, thereby ensuring his own supremacy in the market share of microchip production.

As Zorin, Christopher Walken is a fairly strong villain. But he is surrounded by sheep in wolves’ clothing. Consider the diabolical May Day. After stabbing a French police inspector in the neck with a poisonous butterfly, strangling Bond’s chauffeur (Patrick McNea) in the middle of a car wash and, making numerous attempts to murder both Bond and Stacey, May Day suddenly regresses to the model of a good girl when it is revealed that Zorin is not in love with her. Perhaps then, the best that can be said of

A View To A Kill, is that, like Moonraker, it is a film that begs not to be taken seriously. On that score it is one heck of a good thrill ride.

At $152 million,

A View To A Kill was a sizeable financial success. But the safety net in producing films with weaker narratives, using Roger Moore’s guaranteed box office clout as leverage, effectively became a thing of the past with Moore’s retirement from the series. The next Bond movie would have to stand on its own merit as a compelling piece of fiction, and, it would have to reinvent the character of James Bond once more.

The Living Daylights (1987) became Timothy Dalton’s entrée to the world of James Bond and, in hindsight it is a far more engaging film than critics of its day gave it credit. Following Roger Moore’s departure, Broccoli had courted several possibilities as his replacement, including then relative unknown Sam Neill and Christopher Reeve. But another actor impressed him more: Pierce Brosnan. The star of NBC’s hit detective series, Remington Steele, Brosnan was already a recognizable commodity to audiences – an element Broccoli strongly felt was needed to make the next Bond film a hit. However, NBC’s option on Brosnan’s contract prevented the actor from further consideration – hence, Broccoli returned to a choice he had almost made in 1973.

At last, comfortable that he had attained a level of maturity in his own acting prowess, Timothy Dalton accepted the role of Bond that he had turned down a decade earlier. Encouraged by Broccoli’s desire to return both the character and the franchise to its more earthy roots, Dalton’s characterization of Bond is something of a throwback to Connery in Dr. No and arguably, cannot help but to be judged a thin ghost against that bravado debut in retrospect. Though

The Living Daylights earned an impressive $191 million at the box office, critics were generally unimpressed with both the film and its male lead.

In terms of plot,

The Living Daylights is epically satisfying. After aiding in Soviet General Gregori Koskov’s (Jeroen Krabbe) escape from behind the Iron Curtain, Bond realizes that he has been the unwilling accomplice to an elaborate hoax. Furthermore, he begins to find himself falling in love with Koskov’s paramour, Russian cellist, Kara Milovy (Maryam d’Abo). When the general is recaptured, Bond decides to help Kara escape prosecution by moving her first to Vienna, then Morocco, and finally Afghanistan.

In every way the production is big. From its pre-title sequence, in which Bond and several allies parachute over the rock of Gibraltar, to its stunning car chase staged across the frozen Alps, director John Glen infuses the story with a scope and balance that at least attempted to keep the camp elements at bay. What he is hampered by is a trio of foppish villains; Koskov, the psychopathic, Necros (Andreas Wisniewski) and war enthusiast, Brad Whitaker (Jo Don Baker). None are capable of generating diabolical thrills or innate hatred from an audience. Instead, they appear as three blind mice lined up in sequence for the forgone conclusion of having Bond destroy them en route to the final fade out.

As with

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the narrative structure of

The Living Daylights develops much more detail and depth than most of the films in the series – perhaps as compensation for Dalton’s general lack of striking any indelible impression of his own as Bond. While critics were quick to praise for the most part, and audiences flocked to the tune of $191 million, Dalton’s next endeavor in the series would divide opinion and expectation for the future of the series right down the middle.

License To Kill (1989) is a film that has no middle ground amongst fans of the Bond franchise – one either judges it as a superior departure from the formulaic Bond or dismisses it as not Bondian enough. In the opinion of this reviewer, it is an inanely dismal installment to the series that is best forgotten. Timothy Dalton made his second and final appearance, but this time he transformed the lighthearted and savvy adventurer/spy into a brutish avenging desperado that is more aligned with the villain of the piece, Franz Sanchez (Robert Davi) than with the legacy of James Bond.

After aiding FBI man Felix Leiter (David Hedison) in a drug bust, and standing up at his wedding, Bond returns hours later to discover Felix’s wife murdered and Felix barely clinging to life after being fed to a shark. In an awkward plot entanglement, Bond’s license to kill is revoked by the British government. Now a-wall, Bond pursues Sanchez for revenge in Mexico. On this quest, Bond is paired with Pam Bouvier (Carey Lowell), an undercover FBI agent assigned to pick up where Felix left off. Together they prowl the backstreets of Mexico City, doing battle with Sanchez’s psychotic henchman, Dario (a very young, Benicio Del Toro) while Bond attempts to bleed the kingpin’s maul, Lupe Lamore (Talisa Soto) for vital information.

What is particularly abysmal about

License to Kill is the absence of fundamental elements that audiences have come to expect from a Bond movie; scantily clad women, witty one liners, memorable action sequences – and above all else – a certain amount of seriousness on the part of the actors to suspend the audience in the art of make-believe. Yet, there is nothing even remotely engaging about a misguided vignette that has Wayne Newton cast as a charlatan leader of a religious cult. Nor are there any memorable action sequences of action to fill up the story, which concentrates on Sanchez – sneering and plotting, as other men shoot it out with Bond and Bouvier.

License to Kill premiered at an impressive $156 million, a sizeable financial hit that, in hindsight, accumulated its box office more from audience expectations rather than satisfaction guaranteed. In general, critics were far more dismissive of the film. Timothy Dalton – who had entered the franchise with high hopes, was undoubtedly unnerved by the publicity associated with playing the part. Despite rumors that he was fired, Dalton respectfully resigned from the series by mutual consent, leaving Broccoli once again in search of a mere mortal to fill Bond’s godlike shoes.

By late 1992 both Broccoli and MGM/UA desperately wanted to return James Bond to cinema screens. Lengthy litigation between EON Productions and the aforementioned studio, that had forced the franchise into a hiatus, had been resolved under the latter’s new management and all concerned were anxious to launch another installment in the Bond series. Dalton’s departure was only one hurdle that needed to be overcome. England’s Pinewood Studios – which had primarily been James Bond’s home, were unavailable to accommodate the shooting schedule for Broccoli’s latest and last project –

Goldeneye (1995), forcing the company to virtually build another studio, later named Leavesden, from scratch. Broccoli would die the following year of natural causes, leaving behind a legacy in anthology filmmaking that will likely remain unsurpassed.

Relieved of his NBC contract, and relegated to several years of inconsequentiality as an actor, Pierce Brosnan enthusiastically approached the assignment – perhaps a bit weary that his commitment rested precariously on the shoulders of a studio that could not afford to have a flop. Happy accident for all, that despite an erratic gestation period and rather awkwardly structured script, Goldeneye proved to be anything but a failure.

Imbued with the best elements of the series, (though arguably, the rejuvenation of Miss Moneypenny as a woman much prettier and younger than Bond remains a misfire) including exotic locales and stunning action sequences, Goldeneye proved a notable return to form. The plot concerns a stolen helicopter with nuclear missiles and a rogue element in MI6, Alec Trevelyan (Sean Bean). Once a committed agent, Alec has defected to the Russians who plan to hold the world hostage by using a satellite to zap out potential adversaries from the relative safety of outer space. (This tired pretext had been previously exploited in Diamonds Are Forever and would be reused again as the main threat to world domination in Die Another Day.) Not that audience seemed to mind this retread on old ideas. Upon its release,

Goldeneye grossed a staggering $351 million – a financial success more telling of the rising costs in theater tickets rather than an accurate measure of total audience attendance.

Tomorrow Never Dies

Tomorrow Never Dies (1997) is the least memorable Bond in Brosnan’s brief tenure. Officially launched into production even before

Goldeneye’s release,

Tomorrow Never Dies is hampered by two circumstances: first, that both Leavesden and Pinewood Studios were unavailable to accommodate the shooting schedule – thereby forcing the company to build yet another production facility out of an abandoned grocery warehouse; and second, by MGM/UA’s determination to push onward with a pre-slated release date that effectively provided the shortest period ever for pre-production on a Bond film.

Bond is assigned to investigate the disappearance of a British vessel in Chinese waters. Along the way he comes in contact with egotistical media baron, Elliot Carver (Jonathan Pryce), whose satellite and cable empires span the globe – everywhere except China. Exploiting his communications apparatus to launch WWIII by falsifying news stories, Carver’s trump card is the acquisition of that British vessel. In the meantime, aware that the ship contains valuable cargo, China has dispatched its own undercover agent, Wai Lin (Michelle Yeoh) to Hong Kong where she and Bond find themselves increasingly the targets of assassination attempts. The film’s narrative is superficially complicated by Bond’s reunion with old flame, Paris (Teri Hatcher), who is currently married to Carver.

Despite this fairly cut and dry story, director Roger Spottiswoode struggles to make something of the material he has been given. The first half of the film plays more like a downgraded and retrofitted knock off of David Fincher’s

Se7en (1995), with Bond investing far too much time sneaking under Carver’s radar and getting reacquainted with Paris. The latter half is more on par with the expectations of a Bond action/adventure. Yet, despite an adrenaline pumping motorcycle/helicopter chase, in which Bond and Lin are handcuffed together as they jump over rooftops, the rest of the film come to life only in fits and sparks. And then there is the issue of Lin herself; she’s a Bond girl only by definition; meaning she’s female and she’s working with Bond. There is no sexual chemistry between the two. Worse, Lin seems to take over for Bond on more than one occasion, leaving one with the unnerving question – is this a Kung-Fu flick with Caucasian testosterone thrown in on the side?

More satisfying on every level is

The World Is Not Enough (1999) is an impressively mounted production mired by problematic story-telling – at least insofar as a Bond film is concerned. Rules are rules and the rules of a Bond film have remained: that the villain will always be male; the Bond girl usually scantily clad, and that James Bond is the hero of the day. However, what occurs on this outing is a subversion of these time honored principles. Bond (Pierce Brosnon) is a hapless accomplice to the diabolical machinations of Elektra King (Sophie Marceau). Elektra’s prior kidnapping by rogue nationalist, Renard (Robert Carlyle) has brainwashed her into be his accomplice. After pretending to escape, she murders her father before plotting to systematically dismantle his oil empire, while wreaking havoc on those who were closest to him. That list includes Bond and M (Judi Dench).

The story is an interesting series of action-based vignettes that hark back to the Bond tradition. But the latter half – in which the full wrath of Elektra is exposed - plays more like a Greek revenge tragedy. Through it all, Bond appears to be along just for the ride. He is first made Elektra’s complicit dupe; then the second string to savvy Bond girl, Christmas Jones (Denise Richards), who always seems to know more about what’s going on than Bond does; and finally, the victim of torture that ends only after Bond rival, Valentin Zukovsky (Robbie Coltrane) barges in, is killed by Elektra, but manages to shoot loose the handcuffs that prevent Bond from his escape.

In the final analysis Michael Apted’s direction keeps the pace fast, perhaps too fast to make one forget what a Bond film should really be. The action sequences are visceral, but lack any memorable moments to place them among the best in the Bond canon. The absence of any scantily clad Bondian vixens throughout this excursion is sadly missed. Nevertheless,

The World is Not Enough emerged as a $361 million blockbuster.

The last Bond film to bear Brosnan’s imprint is Lee Tamahori’s

Die Another Day (2002); a glossy retread on the premise previously addressed in

Diamonds Are Forever. Assigned to a rendezvous with North Korea’s Colonel Moon (Will Yun Lee), to capture terrorist, Zhao (Rick Yune) Bond’s mission is compromised and he is taken prisoner. After being severely tortured, Bond is traded to MI6 but relieved of his duties and blamed for leaking information. M (Judi Dench) confides that she can no longer trust him. Bond escapes to Cuba, teaming with sexy diver, Jinx (Halle Berry) a rogue agent who believes that the key to Zhao’s whereabouts lies with mysterious British billionaire Gustav Graves (Toby Stephens).

The plot digresses into fantastic plastic surgeries that have made Colonel Moon’s son and Graves one in the same, thanks to a genetic conversion that, so we are told, is both painful and short lived. Borrowing heavily on the doomsday devices first introduced in

Diamonds Are Forever and

The Man With The Golden Gun, Graves has harnessed the power of the sun in a destructive intergalactic ray gun that can be pointed at any place in the world.

Improbability seems to be the order of the day in this Bond film; in everything from having a posh palace and hotel constructed entirely out of ice, but where the invited guests cavort in skimpy attire and are never cold; to employing the doomsday device to melt the polar ice cap, but not the frozen palace built on it – at least not the room where Jinx has been entombed, this Bond film asks that one throw caution and logic to the wind and just go along for the ride. Bond drives an invisible Astin Martin – another impossibility made possible by digital movie making. Madonna makes an unexpected, but welcome edition to the cast as Verity – referee of a particularly nasty bit of sword play between Graves and Bond. It is the highpoint of an otherwise stagy and clichéd filled adventure yarn.

PARTING THOUGHTS for the adventures of tomorrow

PARTING THOUGHTS for the adventures of tomorrowAnd there you have it: Bond’s cinematic legacy in totem. Cumulatively, the films have been an uneven batch at best – the brightest among them (

Goldfinger, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, For Your Eyes Only, Octopussy) elevating the spy thriller to a hallowed place in the cinema firmament. What is in store for agent 007 in the future? Who can say for certain – but arguably the epitome of the franchise was achieved during the golden aegis of Connery and Moore, and of course, under the formidable and omnipresent guidance of Albert R. Broccoli. For them, and for author Ian Fleming, the world was indeed not enough.

@Nick Zegarac 2006 (all rights reserved).

and fellow writer Al St. Clair turned the German Shepard Rin Tin Tin into a national phenomenon at Warner Brothers. Both Jack and Harry Warner considered Zanuck their protégée – one they would afford every opportunity along the way except total control as Vice President in Charge of Production. After launching the studio into talkies with The Jazz Singer (1929), Zanuck went on to solidify Warner’s gritty stylized gangster/melodrama formula. In the course of six short years he oversaw 300 productions and was arguably the most consistently unbeaten producer in the business. Despite his weekly salary of $5000 the young and aspiring mogul was restless.

and fellow writer Al St. Clair turned the German Shepard Rin Tin Tin into a national phenomenon at Warner Brothers. Both Jack and Harry Warner considered Zanuck their protégée – one they would afford every opportunity along the way except total control as Vice President in Charge of Production. After launching the studio into talkies with The Jazz Singer (1929), Zanuck went on to solidify Warner’s gritty stylized gangster/melodrama formula. In the course of six short years he oversaw 300 productions and was arguably the most consistently unbeaten producer in the business. Despite his weekly salary of $5000 the young and aspiring mogul was restless.