“You were very good at playing a bitch-heroine, but you shouldn’t win an award for being yourself!”

– Jack Warner to Bette Davis on her Oscar win for Jezebel.

Depending on which star or technician you tap, there are as many differing and varied opinions on the legacy of Jack L. Warner as there are films in the Warner vaults.

Although he managed to retain control of his studio longer than his contemporaries – and, produce some of the finest films – in hindsight the tyrannical and wily mogul was a force of nature, whose gale force often blew negativity back in his own direction.

Not that bad P.R. ever ruffled Warner’s proverbial coat of Teflon feathers. He was a man of great determination, considerable stealth in the boardroom and a brilliant strategist. His deft handling of stars and subject matter made Warner Brothers the envy of the best in the business – up to and including MGM.

He was born John Eichelbaum (of Polish-Jewish extraction) in London, Ontario Canada on August 1892 – the youngest of the Warner brothers: Harry, Albert and Sam. For a while, the brothers went their separate ways. Demonstrating a certain degree of talent as a nightclub singer, Jack seemed to prefer the flashy lifestyle that public fame afforded. Although his presence as a movie mogul would eventually dominate the studio and the industry at large (Warner was one of the founding 36 members of AMPAS – the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences), credit for developing that fledgling enterprise cannot be ascribed to Jack L. Warner.

SAM, I AM

Beginning in the early 1900s, Sam Warner had made his reputation as a carnival barker and something of a gregarious showman. Convinced by a friend that Thomas Edison’s primitive Kinetoscope would revolutionize the realm of entertainment, it was Sam who persuaded his brothers to abandon their respective trades and amalgamate their efforts around the new-fangled mystique of ‘the movies.’ Buying a modest store front and padding out the experience with live entertainment, Sam’s ambition and drive were complimented by a blind faith and

optimism. His timing could not have been more perfect. The movies had caught on and so had the Warner brothers.

optimism. His timing could not have been more perfect. The movies had caught on and so had the Warner brothers.Dabbling in the acquisition of independent productions between 1905 and 1912, the brothers Warner had a string of modest successes and failures in their nickelodeon venture. In 1918, My Four Years in Germany, netted the brothers $130,000 in pure profits; enough of an enticement to consolidate their ventures under one company banner in 1923: appropriately named ‘Warner Brothers.’

For the next several years, it remained a small studio – heavily reliant on the exploits of their four-legged star Rin-Tin-Tin, their ‘prestige’ thespian, John Barrymore and the increasingly defiant Darryl F. Zanuck – then head of production.

Once again, it was Sam, not Jack Warner who had seen the future of the industry in a little-plied gimmick: Vitaphone. This crudely rendered sound recording device emanating from wax records synchronized to picture elements would be the studio’s first claim to fame. Ambitiously mounted and expensive to make (it cost $500,000) the overwhelmingly success of their first talking picture, The Jazz Singer (1927) was marred by a personal tragedy. Sam Warner succumbed to a cerebral hemorrhage the night before the premiere.

THE AGE OF GRIT

“I have a theory of relativity too. I never hire them!” – Jack Warner quipping to Albert Einstein.

Returning from Sam’s funeral, the brothers Warner regrouped their efforts – more determined than ever to transform their studio into one of Hollywood’s major players. Albert assumed responsibilities as the company’s treasurer; Harry – the company’s president. But it was Jack Warner who became the defacto mogul in charge of production, a credit he largely ascribed to himself (and one that appeared across the famous Warner shield for many years) despite the fact that company’s initial successes were largely due to the foresight of Darryl F. Zanuck.

Under Zanuck’s ambitious campaign, the studio emerged

triumphant with a string of hard-hitting crime dramas and detective thrillers. James Cagney became their number one box office draw. Zanuck also revived the trend for musicals with 42nd Street (1932) – combining Warner’s gritty style for tabloid ‘ripped from the headlines’ storylines with frothy ethereal concoctions from the man who would leave his imprint as ‘the master builder of the American musical’ – Busby Berkeley.

triumphant with a string of hard-hitting crime dramas and detective thrillers. James Cagney became their number one box office draw. Zanuck also revived the trend for musicals with 42nd Street (1932) – combining Warner’s gritty style for tabloid ‘ripped from the headlines’ storylines with frothy ethereal concoctions from the man who would leave his imprint as ‘the master builder of the American musical’ – Busby Berkeley.However, a personal rift with Zanuck in 1933 resulted in a change of regime. “If it's anything I can't stand it's yes-men” Warner later mused, “When I say no, I want you to say no, too.”

Zanuck departed to co-found 20th Century-Fox and Jack Warner appointed the man who would ultimately become the hidden talent behind the magical output of the studio’s golden era – Hal B. Wallis. If short-lived, the association nevertheless proved extremely profitable. It also produced

some of the most memorable movies in the Warner canon including Confessions of A Nazi Spy, Dark Victory, The Roaring Twenties, The Private Lives of Elizabeth & Essex, The Sea Hawk and Casablanca. It was the overwhelming critical and financial success of this latter film that unfortunately proved the undoing of that lucrative partnership between Wallis and Warner.

some of the most memorable movies in the Warner canon including Confessions of A Nazi Spy, Dark Victory, The Roaring Twenties, The Private Lives of Elizabeth & Essex, The Sea Hawk and Casablanca. It was the overwhelming critical and financial success of this latter film that unfortunately proved the undoing of that lucrative partnership between Wallis and Warner.When it was announced that Casablanca had won the Best Picture Oscar at the 16th annual Academy Awards, Wallis was on his way to the podium when he was cut off by Jack Warner who accepted in his stead and on behalf, not of Wallis, but his studio. The slight was sufficient to sour and severe their tempestuous partnership. Wallis resigned. In fairness to Jack Warner, the producer credit on any film of the period rarely meant widespread public acknowledgement for the producer. As precedence, previous Best Picture Oscars had gone, not to the producer of the film, but to the studio that had funded the project; a practice judged as unfair but not overturned until MGM’s An American In Paris’s took home the statuette in 1951.

Throughout the 1930s and 40s, Warner studios achieved great success with

modestly budgeted fare. While MGM was confounding the public’s senses with glamorous and gaudy entertainment far above the normalcy of every day living, Warner Brothers was producing movies whose plot lines and characters echoed the lowest common denominator of the streets. Dark, sinister, brooding and shot on a budget, the Warner style of the 30s was a text book example of seamless blending between economy and artistry.

modestly budgeted fare. While MGM was confounding the public’s senses with glamorous and gaudy entertainment far above the normalcy of every day living, Warner Brothers was producing movies whose plot lines and characters echoed the lowest common denominator of the streets. Dark, sinister, brooding and shot on a budget, the Warner style of the 30s was a text book example of seamless blending between economy and artistry.If powerful and timely social dramas like I Was A Fugitive From A Chain Gang (1932) convinced Jack Warner of the public’s voracious appetite for this sort of exploitive melodramas, then the failure of expensive fantasies like A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935) confirmed his sound judgment to keep a tight reign on the purse strings. As such, Jack Warner built his star roster, not from glamour queens (like Joan Crawford) or dapper Dans (like Clark Gable), but with a flair and an eye for

solid acting and the un-glamorous. Humphrey Bogart, Bette Davis, Paul Muni, James Cagney: these were the tough-as-nails early draws at the studio. Those critics who described Errol Flynn as a ‘thin pale ghost of Gable’ were missing the point that female audiences had embraced with the Tasmanian actor’s debut in Captain Blood (1932). That Flynn, unlike Gable, was cast as a rapscallion, not a stud, despite his pretty boy looks. While other studios may have developed stars more readily, one aspect about Warner Brothers was undoubtedly the envy of the rest of Hollywood – its bountiful assortment of competent contract players.

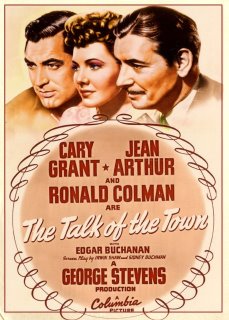

solid acting and the un-glamorous. Humphrey Bogart, Bette Davis, Paul Muni, James Cagney: these were the tough-as-nails early draws at the studio. Those critics who described Errol Flynn as a ‘thin pale ghost of Gable’ were missing the point that female audiences had embraced with the Tasmanian actor’s debut in Captain Blood (1932). That Flynn, unlike Gable, was cast as a rapscallion, not a stud, despite his pretty boy looks. While other studios may have developed stars more readily, one aspect about Warner Brothers was undoubtedly the envy of the rest of Hollywood – its bountiful assortment of competent contract players.From the inimitable Claude Rains to the irascible S.Z. Sakall; the diminutive Peter Lorre, to the formidable girth of Sidney Greenstreet, the studio’s stock company of contract players was as much a selling feature to the paying public as the name above the title. Even the studio’s B-level actors – such as Ronald Reagan, were among the best of

their kind, and often superior to actors billed as leading men at other studios.

their kind, and often superior to actors billed as leading men at other studios.Also integral to the Warner Brothers success throughout the 1930s and 40s was Jack Warner’s ability to procure some top flight talents behind the camera. These included; director John Huston, whose fast paced darkly edged humor complimented the Warner studio style; composer Max Steiner, who scored roughly half of the output of the period, and, choreographer Busby Berkeley and his mesmerizing kaleidoscopic dance routines.

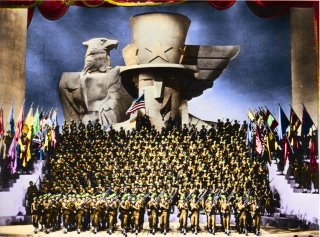

Yet, perhaps no one was more versatile in shaping the Warner film output of the period than director, Michael Curtiz. Curtiz’s adept and masterful handling of every genre known to film made him the busiest director on the backlot – responsible for such diverse projects as the action/adventure yarn, The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) the wartime musical, This Is The Army (1943) and the Oscar-winning film noir, Mildred Pierce (1945).

So intensely engrossed in the business of making movies, that he once was thrown from a moving car because he attempted to simultaneously drive it and write down his ideas for a new project, Curtiz’s volatile Hungarian personality and inferior mastering of the English language was often in conflict with the stars and studio technicians he commanded, though in the upper echelons of the executive boardroom his star continued to rise. For example: Curtiz once admonished an assistant for not fulfilling his wishes by shouting, “The next time I want an idiot to do this, I'll do it myself!”