“Obstacles make for a better picture.” – Victor Fleming

By

September 26, 1938, the official first day of principle photography on

The Wizard of Oz, the film was already two weeks behind schedule. Start up had been delayed primarily to allow Judy Garland to finish,

Listen Darling (1938) the light-hearted minor programmer in which she effectively rocked the house with her poignant version of

‘Zing Went The Strings of My Heart’. However, this pause also gave contract player,

Gale Sondergaard (cast as the Wicked Witch) the opportunity to reconsider how her de-glamorization might impact future procurement of glamour girl roles on the backlot. Sondergaard’s apprehensions eventually blossomed into flat out rejection – a move that temporarily frustrated Oz’s original director,

Richard Thorpe – though Margaret Hamilton quickly essayed into the project as Sondergaard’s replacement.

More alarming on the whole was

Buddy Ebsen’s forced withdrawal from the part of The Tin Man. Ebsen’s makeup, made from aluminum dust had literally coated the actor’s lungs to the point where he could not breathe and had to be hospitalized for over a month. Unable to make a postponement in order to accommodate Ebsen’s extended recovery, the actor was replaced by

Jack Haley, a gifted Vaudevillian; the makeup applications thereafter made of the slightly less toxic mixture of aluminum paste.

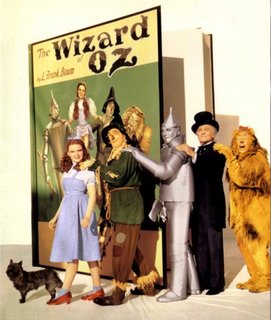

Despite these initial setbacks, what

Arthur Freed and

Mervyn LeRoy found even more unsettling was the handling of Judy Garland’s footage under director Richard Thorpe’s command. Thorpe had transformed this simple Kansas farm girl into a would-be glamour queen – complete with flowing tresses and makeup befitting a runway model. Deeming the footage as unacceptable, Thorpe was removed from Oz on

October 24, 1938.

His replacement was the imminent

George Cukor – on loan from

David O. Selznick. Although Cukor did manage to shoot costume and make up tests before being recalled to Selznick International to begin

Gone With The Wind, his involvement on Oz was minimal, though distinguished. For example, Cukor was largely responsible for transforming

Judy Garland into the image of Dorothy that millions have come to know and love since; stripping away the rubber prosthetic that had been designed to remove the slope in her nose; Cukor, who re-conceptualized

Margaret Hamilton’s Wicked Witch from old hag to severe gargoyle; and finally, Cukor who softened

Ray Bolger’s Scarecrow applications so that his expressive facial gestures could shine through.

Cukor’s replacement on Oz was

Victor Fleming – a determined, enigmatic (some might say, crude), though ambitious director with a proven track record of success, usually on projects that were in distress. Fleming’s passion for filmmaking was matched only by his unadulterated discount for the niceties on the set. He was, after all that has been written over the years, a man of formidable determination.

Fleming’s frank directness did not bode well in particular with actors

Bert Lahr and

Frank Morgan; the latter particularly felt that his best bits of comedy were being usurped by Fleming’s straight forward approach. Undoubtedly, Fleming was determined to maintain a certain mood throughout the production; a mood perhaps tampered with by Morgan’s zeal for hamming it up.

Production began in earnest, despite insufferable conditions exacerbated by the heat generated from 150 arch lamps raised high above the sound stages. Extreme lighting was necessary to compensate for the inadequate levels of color saturation attained on all early Technicolor film negatives. More

disturbing for cast and crew were the constant and daily revisions to the script.

And then, there were the accidents to consider. At one point, a witch’s soldiers stepped on

Toto, forcing

Terry – the original terrier – to be temporarily replaced by another dog. During their flight into the haunted forest a pair of winged-monkey stunt men had to be hospitalized when their wire harnesses snapped in mid-flight.

But by far the most disastrous mishap occurred during the filming of Margaret Hamilton’s disappearance from Munchkinland. The sequence called for Hamilton witch to be engulfed in a cloud of red sulfuric smoke followed by a colossal fireball. Special effects engineer

Buddy Gillespie had tested the hydraulic trap door on which Hamilton stood prior to executing this sequence. However, as the cameras rolled, the hydraulic lowered Hamilton too slowly – the net result, her upper extremities and face were engulfed by the fireball.

Remembering that Hamilton’s green applications had incorporated flammable copper, specialist

Jack Dawn managed to save the actress from severe scarring and disfiguration by working quickly to peel off her makeup. In the middle of all this chaos, MGM seriously contemplated canceling the project – a move that sent

Arthur Freed flying into L.B. Mayer’s office declaring loudly,

“If I had two and a half million I’d buy this picture from you. It’ll be worth more than that someday!”

By

December 28, 1938 one of film history’s most intricately staged and most fondly remembered sequences – Dorothy’s arrival into Munchkinland was completed without further incident.

Despite numerous stories over the years that have disseminated myths about the singer midgets as a collective body of drunken and disorderly reprobates, only a small percentage of ‘the little people’ indulged in such behavior behind closed doors and off the set.

By

February of 1939, nearly all of the Technicolor portions of Oz had been completed. Victor Fleming left Oz to assume directorial responsibilities on another troubled endeavor – Selznick’s

Gone With The Wind. With Fleming’s departure, veteran

King Vidor assumed the directorial reigns. It is Vidor, not Fleming who was responsible for photographing the memorable Kansas bookends, the spectacular tornado sequence, and footage involving Dorothy’s first meeting with Professor Marvel. As these sequences neared completion, dance choreographer

Busby Berkeley was brought in to stage an extended dance sequence for Ray Bolger’s Scarecrow.

As Oz officially entered postproduction,

Victor Fleming returned to help tighten the film’s narrative in the editing room. Prior to the second sneak preview in Pomona, Vice President

Eddie Mannix had Garland’s immortal

‘Over the Rainbow’ excised with the complicity of six executives because he felt the song tended to slow down the narrative. Outraged,

Arthur Freed and

Mervyn LeRoy launched their own successful counter campaign and the song was quickly reinstated by the third preview in San Luis Obispo.

Other sequences were not so fortunate. Despite having toiled on a dance he considered one of his finest, the Ray Bolger/Busby Berkeley collaboration on the scarecrow dance did not survive. Also entirely removed from the final cut was Dorothy’s reprise of ‘Over the Rainbow’ in the witch’s castle, the lavishly staged triumphant return to the Emerald City following the witch’s demise, and several minor comic bits of business. By the end of

July 1939, MGM was diligently working to produce five hundred prints of Oz for distribution.

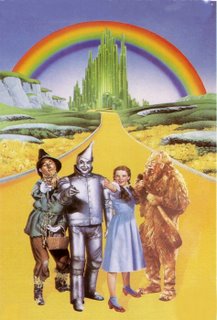

In totem, Oz had been in production for nearly ten months and had cost MGM just under three million dollars; a gargantuan sum for its day. The accolades the film received upon its private screening from the critics confirmed Oz’s place in entertainment history.

James Francis Crow of the

Hollywood Citizen News was among the first to proclaim,

“The Wizard of Oz is a great motion picture. It is not only a magnificent, history-making technical achievement: it is a warmly human, deeply emotional photoplay too.”  Edwin Schallert

Edwin Schallert of the

Los Angeles Times declared,

“Fantasy is at last brought to the screen in full-fledged form and a victory.”Picture Reports published a glowing accolade that began,

“Surpassing all previous screen extravaganzas in the mammoth scope of its production, Oz commands superlatives from critics and the public alike. It is truly a magnificent spectacle, a towering achievement in the technical magic of motion pictures.”Had

The Wizard of Oz been produced during any other year it would have easily swept the Academy Awards. Unhappy chance for the film, that it was released in 1939; the greatest year in motion picture history. Buffeted on all sides by worthy Oscar contenders, Oz remained the leading contender for Best Picture until David O. Selznick’s

Gone With The Wind debuted. Thereafter, despite its overwhelming positive reviews and grandiose sense of technical accomplishment, Oz became just another footnote to that illustrious year in movies. It would take a reissue in 1949 for the film to recoup its production costs and, in fact, turn a profit.

Mervyn LeRoy, who immediately following Oz’s triumphant premiere gave up producing to return to his first love – directing – may not have won an Oscar, but he arguably received the penultimate congratulatory salutation for his efforts. Upon winning her Oscar for Best Performance by a juvenile,

Judy Garland scribbled a message to LeRoy on her napkin –

“I owe you everything, Mr. LeRoy,” it read.

What has kept

The Wizard of Oz alive for so many and for so long since is not its technical achievements – as fine and as startlingly surreal as they are and continue to be. No, in the final analysis the proof in Oz’s purpose remains clear in its emotional depth; to find one’s place in the world not through the magical dabbling of some omnipotent power, but at the very heart and soul of one’s own courage to will a dream into reality. And even if the world at hand does not present itself under the most ideal of circumstances, the film’s underlying message is pointed clear; there is still no place like home. Fantasy would never again be quite so honest or appealing.

@ Nick Zegarac 2006 (all rights reserved).

d their own 1902 production; a reconstituted flashy – if misguided – musical comedy more attuned in sentiment and tastes to unrelated Vaudevillian hokum than Baum’s original clairvoyance for epic fantasy. Arguably an artistic misstep, Oz’s debut in live theater nevertheless created a minor sensation, running a then record 293 performances before going on a country-wide tour that lasted until 1911.

d their own 1902 production; a reconstituted flashy – if misguided – musical comedy more attuned in sentiment and tastes to unrelated Vaudevillian hokum than Baum’s original clairvoyance for epic fantasy. Arguably an artistic misstep, Oz’s debut in live theater nevertheless created a minor sensation, running a then record 293 performances before going on a country-wide tour that lasted until 1911. emerge from independent Chadwick Films. But the movie veered wildly beyond the scope and intelligence of the original work and proved a quick and easily forgotten flop.

emerge from independent Chadwick Films. But the movie veered wildly beyond the scope and intelligence of the original work and proved a quick and easily forgotten flop.

concocted two original characters not in Baum’s books the operatic ‘

concocted two original characters not in Baum’s books the operatic ‘ musically to handle the demands of Dorothy, Temple was much closer in age to Baum’s heroine as written than

musically to handle the demands of Dorothy, Temple was much closer in age to Baum’s heroine as written than