The Idealism of King Arthur in Tennyson's "Idylls of the King"

Why does man seek the Ideal so ardently? Because this world is so soiled, corrupt, debased, evil, and fallen. Genetically, and in terms of behavior, we’re not that much different than baboons—and not very nice baboons at that.

That’s one of the points Aldous Huxley was making in his black, despairing post-Bomb satire Ape and Essence (1948), one of the very darkest works of twentieth-century literature.

In Western thought, Plato originated the concept of the Ideal, and his worship of the Ideal has shaped Western thought like few other ideas.

What is Christianity but naked neo-Platonism? Everything about Christianity screams neo-Platonism—Christ is the incarnation of the Ideal, and his life is the story of how shabbily and viciously the Ideal is treated in this base world.

The story of the Virgin Birth is a metaphor for how miraculous it is that that anything decent, kind, and transcendent exists in this fallen world.

The point of the story of the Crucifixion is that evil is bent on destroying anything good and decent in this world, but the story of the Resurrection tells the tale of how the Ideal will triumph over the malevolent machinations of this world and ultimately emerge victorious.

Most of the Christian Era—especially the Dark Ages and the Middle Ages—was obsessed with the totemization of the Ideal. The flesh—the Real—was despised and seen as something to be conquered and overcome; hence the primacy in medieval times of the mortification of the flesh.

Nietzsche saw this and warned: “Be true to the things of the earth.” We’re flesh and blood too, you know, and that’s not too bad. The Puritans inherited this neo-Platonic worldview, and their unrealistic “idealism”—demanding perfection of flawed human nature—has poisoned much of American culture.

Post-Darwin, the Victorians commonly saw man as a being whose state was frozen between ape and angel—tied to the bestial by the nature of the flesh, but at the same time striving to achieve the perfection and purity of the Spirit. Nietzsche (who lived during the Victorian Era) dreamed of transcendence and imagined his Overman not as a genetic superman, but a common bourgeois European who was trying to overcome the mediocrity, stupidity, and narrow-mindedness of Victorian Europe—someone who was trying to overcome themselves.

The great British science-fiction writer Olaf Stapledon (1886-1950)—Oxford graduate, philosophy professor, and the only SF writer who can be considered as great as H.G. Wells as a purely literary writer—imagined in his masterpiece Last and First Men (1930) that man’s evolutionary destiny was to break free of the bonds of the flesh and become pure energy, unfettered spirit, living mental energy, the ape changing into the angel.

The famed Outer Limits episode, "The Sixth Finger," starring David McCallum as the man of the future, was clearly based on Stapledon's masterpiece Odd John

Stapledon, although largely unknown to the general public, is with Wells the most influential SF writer of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries; Arthur C. Clarke’s ideas of man evolving into pure energy in Childhood’s End and 2001 are taken directly from Olaf Stapledon.

In The Idylls of the King—acknowledged as the unquestioned poetic masterpiece of British Victorian literature—Tennyson is clearly obsessed with this concept of the Ideal. No wonder: he lived in an era where grim, ghastly Dickensian poverty (vicious economic exploitation) existed side-by-side with astonishing technological advances (the locomotive, the telegraph, the electric light, to name a few), a civilization that was worshipping Progress just so that it could blow its brains out a short time later in the First World War. Behind the daguerreotype façade of scientific wizardry and social advance, Jack the Ripper was just waiting to do his thing.

Tennyson makes his hero King Arthur’s attempt to create an ideal society the centerpiece of his book. He wasn’t just talking about the shortcomings of British Victorian society; he meant for his tale of the quest for an ideal social order to have universal appeal.

The stunning Keira Knightley as Guinevere in King Arthur (2004)

I originally wrote this essay while a senior at

We in

Of course, FDR couldn't be elected to the White House today. With those legs, are you kidding?

But in the early Fifties, the Republicans knew there was only one way they could unseat the Democrats after 20 years of occupying the White House—and that was by manufacturing, via the Big Lie, a false Red Scare, accusing the Democrats of treason, which Joe McCarthy was only happy to do for the GOP, with behind-the-scenes support from J. Edgar Hoover.

J. Edgar Hoover: rooting out subversion at the highest levels of the

Richard Nixon rode that scummy wave to power, as did Ronald Reagan, and to this day it astonishes me that those finks could deliver outrageous lies like George Marshall and Dean Acheson were Communists or Red tools, and they never had to pay the price in American public life for spreading outrageous lies.

They should have been excommunicated from American public life, but instead Richard Nixon became the man who most shaped postwar

Adlai Stevenson was a shining knight of postwar American idealism, but as an intellectual in the Fifties, he was derided as an "egghead"

Contemporary American audiences might be most familiar with the story of The Idylls of the King through the 1960 Lerner and Loewe musical Camelot (based on T.H. White's The Once and Future King).

On Broadway, the great Richard Burton played King Arthur and Julie Andrews was Guinevere

In the early Sixties, of course, “Camelot” became the nickname for the John F. Kennedy administration, the new Golden Age that would transform American society from the mediocrity of the Eisenhower administration to Plato’s Republic governed by philosopher kings (uh-oh).

Well, as David Halberstam recorded in The Best and the Brightest, the “philosopher kings” of the New Frontier really didn’t give a damn about morality, and they allowed

As Seymour Hersh reported in The Dark Side of Camelot, JFK seemed more concerned about orgies in the White House pool than governing the country.

Happy birthday, Mr. President: despite their enviable glamor, a terrible doom was waiting for them both

JFK shared beautiful Judith Exner with Chicago mobster Sam Giancana, which was awfully nice of him

To become President, he spent almost a million dollars in bribe money to buy the

He approved the assassinations of Lumumba,

What a Roman

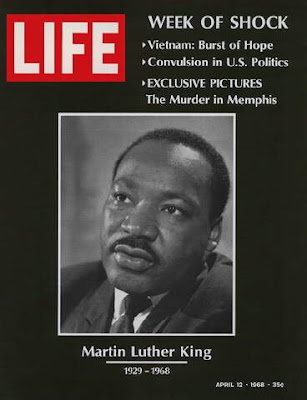

At the end of the Sixties, something happened that everyone knows, but nobody talks about—the Establishment crushed the spirit of the American people.

The same Hidden Hand that operated in

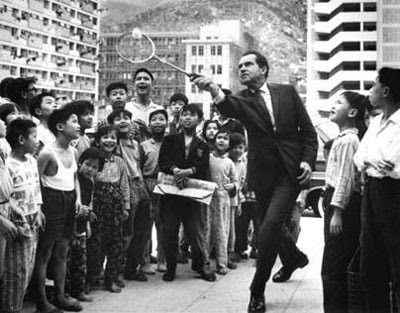

In the spring of 1968, we all know what happened. Witnesses to King’s assassination in Memphis testified that they saw men firing from the bushes, from below King’s motel room balcony; James Earl Ray was supposed to be across the street, and for him to have fired while lying across the bathtub (as he was accused of doing), his elbow would have to have been six inches inside the wall (an impossibility).

The bullets that killed Robert Kennedy came from behind, at close range. Sirhan Sirhan was firing from in front, six feet away; but standing directly behind RFK was a security guard named Thane Eugene Cesar, a member of the John Birch Society who was called in at the last minute to work at the Ambassador Hotel as a security guard.

Witnesses saw him bring his arm up and fire his pistol right behind Robert Kennedy, and from what I understand, you and I can still go to L.A. and have a beer with him and chat about what happened and what it was like watching Bobby Kennedy die at your feet. Any takers?

(See the shocking 1973 film documentary, The Second Gun, which shows you how you can kill someone of the prominence of Robert Kennedy in this country—so that everyone knows you did it—and still get away with it.) Also read Shane O'Sullivan's amazing November 20, 2006 Guardian article, "Did the CIA Kill Bobby Kennedy?", which reveals that three CIA agents with no reason to be in the U.S. happened to be in the Ambassador Hotel at the time of the shooting.

The Establishment made it very clear that any national leader who tried to stop the Vietnam War in 1968 was asking to get killed, and after Nixon took power (because his ally Madame Chennault told the South Vietnamese not to negotiate with Hanoi until Nixon was elected), he made it his job to crush the blacks and break the back of the Left.

Senator Eugene McCarthy, a remarkable Stevensonian idealist, valiantly tried to stop the Vietnam War in 1968, but two assassinations got in the way

Nixon and Agnew turned the working class (the “hardhats”) against the antiwar middle class, and in May 1970, someone told the Ohio National Guard that it was okay to use live ammo on the kids at

As soon as four white kids were murdered for opposing the war in

1972 Democratic Presidential candidate George McGovern, one of the shining knights of American idealism: he did his best to stop the Vietnam War

Thus was born the Me Generation, and the American public drifted into so-called privatism (tending your own garden, as Candide said), advanced materialism, depression, alcoholism, mental illness, drug abuse, cultic behavior (pick the cult, from Jesus freaks to EST), desperate self-help fads, resurgent Born-Again fundamentalism, disco, the Joy of Sex, and any other form of escapism that you can imagine. Oh yeah, and in 1976 Steven Spielberg began destroying serious

A feeble retelling of Moby Dick

In 1977, George Lucas followed up with the coup de grace by delivering Star Wars, a special effects extravaganza based on a clichéd genre everyone in SF considered too juvenile beyond belief for use in a serious film, the space opera (created in 1928 by The Skylark of Space by E.E. “Doc” Smith), with a plot stolen from Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress and equal parts lifted from The Hero of a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell (which all of us bright young mythopoetic/SF fan types were reading in the Seventies), A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs, the Buck Rogers/Flash Gordon comic strips and Thirties movie serials, and John Ford Westerns (the burned house in The Searchers).

When Mark Hamill reported to the set of Star Wars, he saw the costume for Darth Vader and thought, "Oh, it's Doctor Doom."

Frank Frazetta's beautiful cover painting for A Princess of Mars

All that was left was for Big Oil to use the Iranian Revolution as an excuse to double gas prices (with only a 5% decrease in supply), and all the discretionary income got sucked out of the Western economy as gas lines stretched across America. For the first time, Americans were terrified that they wouldn’t be able to drive to work and that without gasoline, civilization was in very real danger of collapsing.

The Road Warrior (1982) is very much an expression of that dire social panic and hysteria—which I believe was designed to soften us up for a right-wing demagogue like Ronald Reagan, or Grandpa as I like to call him.

Just as Nixon stole the 1968 election through Madame Chennault’s political espionage and back-channel diplomacy, so Reagan stole the election in 1980. Evidence indicates that Reagan’s campaign chief William Casey learned of Carter’s April 1979 Iranian hostage rescue attempt through his network of ex-CIA and ex-FBI agents; the Reagan camp gave the Iranians advance warning, and that’s why the Iranians were ready when the

Once in office, Reagan bankrupted

Reagan had the same kind of effect on my generation, which came of age in the Sixties, as the First World War had on the Lost Generation—we lost our faith in the inevitability of social and political progress, and we saw that reason had no place in governing the affairs of men. Not when the fools and the hard-hearted were running the show. Things weren’t going to get better, necessarily; in fact, it was very easy for our Space Age society to jump back into the robber baron days of the Gilded Age.

As for George H.W. Bush’s first Gulf War, I have to agree with what I heard Kris Kristofferson say at a Greenwich Village nightclub performance in 1991—“If it takes killing 200,000 innocent people to make this country feel good about itself, that’s pretty sorry comment on America.” And as for the post-1987 crash, post-S&L looting of the economy at that time, around 1991, all I can remember is seeing all the boarded-up storefronts along

In Japan, President George H.W. Bush has a delayed reaction to serving eight years as Ronald Reagan's butler

In Japan, President George H.W. Bush has a delayed reaction to serving eight years as Ronald Reagan's butlerHow much money did he take from China? Is that why he sat still for the impeachment proceedings--he preferred sex charges to treasonous foreign bribery accusations?

We can blame Bill Clinton for the fact that George W. Bush was able to assume office and institute his nervy, under-the-table dictatorship.

Our Helen of Troy: isn't America amazing?

Linda Tripp was obviously a Republican secret agent; she was working with literary agent Lucianne Goldberg, a former “political operative” in the Nixon White House, and when Tripp met Monica Lewinsky, she was hunting for the goods on Bill Clinton on the behalf of the GOP.

When I first listened to her tape-recorded conversations with Monica, when she’s gently pumping Monica for information about the affair and leading the distraught young woman on, I could only think of Roger Chillingsworth in The Scarlet Letter and his secret psychological manipulation of the distraught Reverend Arthur Dimmesdale, the man whom he knows knocked up his wife Hester Prynne; Hawthorne knew that one of the worst sins you can ever commit is to fuck around with someone else’s head, to violate the sanctity of their soul.

Then Bush the demagogue showed up. In early 2000, I spotted him right away for what he was: a paranoid psychopath with narcissticistic tendencies. The closest recent world leader who fits that description was, unfortunately, Stalin. Otherwise, we’re talking about the unspoken terror that haunted all of us while watching

Don’t get me started on 9/11. I was living in

According to journalist Wayne Madsen, in 2003, during the runup to the invasion of Iraq, Pope John Paul II feared that Bush was the anti-Christ, and the Pope wished he was younger and in better health so that he could properly combat the Beast of Revelation

I trusted Bush for the first week—I couldn’t believe that any American President would try to capitalize on a horrific national tragedy like 9/11—but soon his bellicosity emerged, and my political antenna went up immediately. I realized quickly that Bush wasn’t interested in getting the bastards who’d attacked us; he just wanted to use the attack as an excuse to cement American world military hegemony and institute a full-grown police state in this country. If you want to read an interesting take on 9/11 and its aftermath, check out a very political online comic strip entitled Dies Irae written by Justin Wertham and illustrated by the great Sixties underground cartoonist Spain Rodriguez, creator of Trashman and co-founder of Zap Comix.

Ever wonder why Bush hasn’t bothered to capture Osama bin Laden? I’ve got an idea. Fahrenheit 911 verified beyond the shadow of a doubt the very close financial ties between the Bushes and the bin Laden family in

As soon as Jose Padilla (the “dirty bomb” suspect) was arrested in 2002 and not allowed to see a lawyer, much less a judge or a jury trial, there should have been an outraged general strike in this country, but Americans were too busy following Bush’s advice and going shopping as a patriotic gesture to bolster the sagging 9/11 economy.

Then came the Iraq War. In 1999, Bush was interviewed by Houston Chronicle sportswriter Mickey Herskowitz, a friend of the Bush family, a biographer of Prescott Bush and George W. Bush's former ghostwriter; Herskowitz was hired to ghostwrite Bush’s 2000 campaign book, A Charge To Keep. Bush revealed to him that once he took office, he wanted to invade

Journalist Russ Baker revealed the whole astonishing story here:

“He was thinking about invading

According to Herskowitz, George W. Bush’s beliefs on

Bush’s circle of pre-election advisers had a fixation on the political capital that British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher collected from the Falklands War. Said Herskowitz: “They were just absolutely blown away, just enthralled by the scenes of the troops coming back, of the boats, people throwing flowers at [Thatcher] and her getting these standing ovations in Parliament and making these magnificent speeches.”

Republicans, Herskowitz said, felt that Jimmy Carter’s political downfall could be attributed largely to his failure to wage a war. He noted that President Reagan and President Bush’s father himself had (besides the narrowly-focused Gulf War I) successfully waged limited wars against tiny opponents –

It starts with one person: Cindy Sheehan was instrumental in cracking Bush's invulnerable facade in 2003--he was obviously afraid to meet with her

In addition to Cheney, Rove was clearly pushing Bush to invade

Historians, and our descendants, will look back on the coerced run-up to the Iraq War in 2002 and 2003, and they’ll be astonished (and ashamed of us) that it was so easy for Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz (remember him?), Rice, and Powell to con us.

A terrifying cross between Father Chronos and Pluto, Lord of the Underworld: Christ, he shoots his friends

Puritanism teaches us that in a time of crisis, the Lord is really testing us; that’s when you really see what someone is made of. If that’s the case, then the forced runup to the Iraq War certainly showed us what the moral constitution is of some of the most prominent members of our society. When Bush took office, a lot of us on the Left were counting on the

At the time when the Bush Administration was ramming through the invasion of

Why isn’t there a prominent American who’s so upset by the prospect of a criminal and disastrous invasion of Iraq that he’s willing to spend $2 million (or however much it would take) on a tireless nationwide public speaking tour denouncing the war in order to sway public opinion, widespread public condemnation be damned? Why isn’t an American on the order of Bill Clinton or Al Gore or Jimmy Carter putting his reputation on the line to prevent this horrendous (and avoidable) train wreck?

William Lloyd Garrison didn’t stop until slavery had been outlawed in this country. That man couldn’t sleep for 35 years until slavery had been vanquished in the

“Where is our William Lloyd Garrison today?” I kept asking myself when it was clear that Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, and Wolfowitz were forcing the Iraq War on the trusting American people. "Why aren’t there any great Americans today who care that much about their country?"

As it turned out, there was a handful of great men around the world who spoke out publicly and tried to prevent this outrage—Nelson Mandela, Pope John Paul II, Jimmy Carter, Al Gore, and Howard Dean—and we all know how they were treated by the media: like they were child-molesting Commie weirdos.

They were marginalized, ostracized, mocked. Like the Dixie Chicks, or Howard Dean, whose “Dean scream” (a spirited ya-hooo!) was pounced on as a sign of emotional instability, when in fact it was nothing we haven’t seen at a football pep rally or an evangelical camp meeting.

At Princeton in 1975, when I was concerned that the

Emory’s point was that things could be much worse. If the American public hadn’t protested against the Vietnam War,

Maybe it’s not amazing that when push came to shove, the privileged leaders of our society did not try to prevent a very cruel Juggernaut from crushing

This is why Tennyson still speaks to us in Idylls of the King. As Americans, we are keenly aware of how our cherished ideals have been betrayed, and we are still waiting for a King Arthur—and not some tarnished Lancelot like JFK or Bill Clinton—to heal us and redeem us.

* * * * *

Tennyson's Ideal of King Arthur in The Idylls of the King: Toward a Man With Wings

At the heart of the Idylls of the King lies Alfred Lord Tennyson's ideal conception of the character of King Arthur, who is repeatedly dubbed "the blameless King." Arthur's importance as a moral force in the world of Tennyson's epic cannot be underestimated. As Percivale observes: "King Arthur made/His Table Round, and all men's hearts became/Clean for a season" (p. 173). The old Seer whom Gareth encounters on the road to Camelot is even more telling concerning Arthur's moral standing:

...the King

Will bind thee by such vows as is a shame

A man should not be bound by, yet the which

No man can keep (p. 33).

In Arthur, Tennyson sought to erect a moral exemplar suitable to Victorian society in an age wracked by religious doubt, the explosion of Darwinism, and the birth-pains of massive industrialism and its multiplying social problems. Besieged by these manifold dilemmas (which often attacked in concert), absolute standards and traditional moral conventions suffered terrific breakdowns, and as a step toward remedying this cultural crisis, Tennyson strove to construct a workable moral ideal. He is often rebuked on the grounds that the Idylls is a retreat into medievalism, but to any careful reader it is readily apparent that Tennyson is hardly taking refuge in a romanticized past.

Rather, in line with the greatest Victorian thought, he is producing an exciting synthesis of the finest of traditional culture with the inescapable realities of the Victorian world, particularly the theory of evolution.

Unlike some modernist writers who practice hermetic art for art’s sake, Tennyson does not retreat from the social, intellectual, and technological situation at hand. Instead, he chooses to face it and adapt it for his purposes. The Idylls of the King is no celebration of the dead glories of chivalry, similar to William Morris' romances.

Tennyson uses the Arthurian cycle as a vehicle for a modern fable mounted on the profoundest scale conceivable. By including clear references to evolutionary theory and the burgeoning hypocrisy, moral relativism, and eroding faith of his time, Tennyson presents the symbolic story of the dream of Arthur and the fall of Camelot as a recurring pattern that takes place in every stage of human society, moving towards a progressive end.

It is, as Tennyson himself stated, an "old imperfect tale/New-old" (p. 254). Thus he pointedly directs a message of the deepest moral sincerity (in the Victorian sense) to his readers, and so manages to create a believable moral hero for his time.

FDR is wearing a black mourning band out of sorrow for the men he's sending into combat

On the surface, Arthur can be seen merely as a hero whose inspiration lies rooted in British nationalism. The whole poetic cycle is dedicated to the late

Indeed, Arthur appears to be a paragon of British nationalism. He unites

In any event, Tennyson powers the Idylls with moral implications that are by no means limited to

Yet the Idylls is no mere recapitulation of neo-Platonism. For an age whose Christian faith in a guiding

From the outset, the saga of Arthur is presented in an evolutionary framework. At the beginning of "The Coming of Arthur," Tennyson declares,

And so there grew great tracts of wilderness,

Wherasin the beast was ever more and more.

But man was less and less, till Arthur came.

For first Aurelius lived and fought and died,

And after him King Uther fought and died,

But either fail’d to make the kingdom one.

And after these King Arthur for a space... (p. 15).

Tennyson deliberately constructs the above passage to suggest an evolutionary pattern. First, in the natural state of the wilderness, anarchy, represented by "the beast," runs riot. Then comes civilization, in the form of the Romans under Marcus Aurelius, to impose order on the heathen wilderness of

Arthur follows. He advances evolutionary progress through a decisive conquest of natural chaos—he unites

The above passage contains the ultimate meaning of the book. On first reading, "The Passage of Arthur" appears to present a pessimistic ending. Arthur's kingdom lies in ruin, the age of Camelot has died with its founder, and it is the end of an era. But when the preceding passage is considered, one sees the ending presages not the last days but a new beginning. Arthur's career must be viewed as part of the schema of existence. It is a significant part, to be sure; he is the first to unite

But the eventual dissolution of his kingdom does not mark the permanent victory of confusion. Just as Arthur succeeded Aurelius and Uther and built upon their pioneering efforts, so will another leader follow him and undertake the long laborious enterprise of reconstructing the kingdom; and just as Arthur advances one step beyond his predecessors, rectifying their failure to unite

And so progress inches ahead. Doubtless each leader will fail in terms of the short run, but through renewed struggle and a successive accumulation of achievements, progress will be attained. In biological terms, Arthur would be classified as a mutant.

As a sport, he stands out significantly from his fellows, and for that reason, he makes major demands on them. But as with all mutants, his auspicious advent heralds a new strain in humanity, a new race of men, a biological advance. His very appearance is an unmistakable sign of progress; Tennyson's Victorian readers, well versed in The Origin of Species, would have recognized him as a hopeful portent at once.

As in the case of all mutants, Arthur is eradicated quickly. His ecology, as it stands, has no place for him. But his powerful influence as a mutant necessarily introduces a profound factor in his environment, and so the world will eventually have to make a place for his kind, especially as his strain, now unique, becomes dominant.

Was Einstein a biological sport, a mutant--the next step in human evolution? His brain was so far in advance of the rest of us, you have to wonder if he wasn't genetically or biochemically different

Assuredly, nowhere in the Idylls does Tennyson state this train of reasoning this baldly, but it is everywhere implicit in the text. As has been shown, he purposely places at the very start of the saga a key passage (“And so there grew great tracts of wilderness…”) that provides the germ from which the logical progression detailed above naturally evolves.

Toward the end of the poem, in "Guinevere," Arthur visits the unfaithful Guinevere in the nunnery. Forced to come to terms with the dissolution of his kingdom and his dreams, he delivers a speech wherein he expounds Tennyson's evolutionary thesis point for point:

For when the Roman left us, and their law

Relax'd its hold upon us, and the ways

Were fill'd with rapine, here and there a deed

Of prowess done redress'd a random wrong.

But I was first of all the kings who drew

The knighthood-errant of this realm and all

The realms together under me, their Head,

In that fair Order of my Table Round,

A glorious company, the flower of men,

To serve as model for the mighty world,

And be the fair beginning of a time (p. 235).

Here, substantially, is all of Tennyson's argument for evolutionary progress; the original institution of order (by the Romans), its lapse into anarchy, and yet its heritage too—"here and there a deed/Of prowess done redress’d a random wrong"—"random" underscoring the entropy overcome by the remnants of order. Then comes Arthur, to introduce the resumption of order ("Order," of course, bearing a double meaning) "To serve as model for the mighty world,/And be the fair beginning of a time."

Through his Order, Arthur labors to provide a moral exemplar that will establish an apocalyptic era. As he departs in his funeral barge, Arthur repeats to Bedivere the words with which he initiated his reign: "The old order changeth, yielding place to new" (p. 251). Despite the weariness and ambiguity of Arthur's closing speeches in "The Passing of Arthur," the above statement is the most telling, delivered instinctively and ending Arthur's tenure on earth as he began it. Its circular quality bespeaks the cyclic nature of the evolutionary process, and its content represents Arthur's faith in Darwinian progress. His order (and mode of instituted ordering) is dying, but in time a new regime will arise, and order will be imposed, of a different kind, admittedly. Unspoken is his belief that just as he arose to realize his ideals in an England reclaimed by the beast, following the departure of Roman law, so will another visionary idealist appear to put his dreams in action in an England disrupted by Modred's style of entropy, following the disintegration of Arthur's Order.

The charge has been leveled at the Idylls that it is an epic without a hero. Yet despite the fact that Arthur is not the central figure of each Idyll, his moral presence dominates the whole body of the book, for the Idylls describe the progressive degeneration of the Order based on his ideal. Another reason Arthur is not present in every episode of the epic of which he is the hero is that he is not a traditional epic hero. He is not simply a doer of mighty deeds or a culture hero. For Tennyson he is the living personification of the Ideal on earth—thus the mysterious circumstances that surround his birth. His entrance into this world is miraculous, just as is the advent of any ideal of perfection into this flawed world.

Because of Arthur's symbolic identity as the Ideal, the epic that celebrates him is devoted to the progress of his ideal as he attempts to establish it in his realm. Tennyson realized that the best way to dramatize his point was to illustrate the struggles of Arthur's subjects as they toil toward their King's ideal. Arthur's ideal of perfection is a supremely noble one. Of his knights, he says:

I made them lay their hands in mine and swear

To reverence the King, as if he were

Their conscience, and their conscience as their King,

To break the heathen and uphold the Christ,

To ride abroad redressing human wrongs,

To speak on slander, no, nor listen to it,

To honor his own word as if his God's,

To lead sweet lives in purest chastity,

To love one maiden only, cleave to her,

And worship her by years of noble deeds,

Until they won her (pp. 235-6).

Of particular importance is the fact Arthur requires his knights to swear their oath of honorable conduct, for he knows that a moral code can only be implemented through an effort of the individual will, which the act of swearing comprises. Arthur knows he cannot impose his ideal from without. His subjects will have to carry it into action because of their faith in his dream and because their honor—their self-respect—has been placed at stake as a consequence of their oath.

Arthur practices what he preaches. As the old Seer informs Gareth, Arthur will not tolerate lies (p. 34). As Arthur remarks, "Man's word is God in man" (p. 18); what is most sacred and noble in humankind is the devotion to the truth. Arthur dispenses the Christian justice of "that deathless King/Who lived and died for men" (p. 36), who of course is Christ, by refusing to incur capital punishment against wrongdoers, instead favoring the Last Judgment. In his court, he seeks to rectify the wrongs committed by his father Uther (p. 35), and he puts great stock in honor. Not only does he refuse the villain Mark’s knighthood, but he eschews custom and spares the messenger of unpleasant news (p. 37). As a result of his conduct, his court provides an atmosphere where Edyrn is able to reform by beginning a new life with a clean slate (p. 99). Arthur considers Edyrn's moral rebirth a superior achievement to any of his knight's quests (p. 100).

Senator Robert Byrd, a former Klansman, became a brilliant crusader against the Iraq War

Each successive tale of "The Round Table" records the encroaching devolution of Camelot, just as the Old Testament records the inevitable gradual corruption that comes to infest the institutions based on Hebrew ideals, beginning with the Fall. By the same token, Tennyson is commenting on what he sees as the decay and cant of Victorian society.

In "Gareth and Lynette," the strength of Arthur's ideals is fresh enough to enable Gareth, through patience and nobility, to overcome Lynette's petulance and eventually win her love. At the beginning of the story, Tennyson is pointedly observing the common pattern in his day of ambitious British rural youth deserting their hometowns for the excitement of the cities, and later, in the court scenes where Gareth absorbs abuse as a kitchen slavey, he is making a statement about the exploitation inherent in the English social class system.

In "The Marriage of Geraint" and "Geraint and Enid," Tennyson is attacking Victorian hypocrisy; Geraint's removes

The decisive break in the moral course of the epic occurs in "Balin and Balan" and particularly "Merlin and Vivien." In both tales, the precipitant cause of this break is the malevolent influence of Vivien, Tennyson's symbol of the perverse impulse. Balan's warrior virtues degenerate into fits of rioting insanity.

General Thomas Power, head of the Strategic Air Command, was considered unhinged by Curtis LeMay and insane by Daniel Ellsberg, who interviewed him as a State Department employee under Kennedy. With

Merlin, the personification of the cognate faculties, the wisdom of Arthur's realm, succumbs to Vivien's allure, when his reason has cautioned him full well; he gives in to his self-destructive impulses, symbolized by the spell of domination Vivien so hungers for. So fall both the military and the intellectuals.

The sour Paul Wolfowitz, architect of the Iraq War

Neocon William Kristol, who thinks an American Empire is a really good idea

"Lancelot and Elaine" discredits the validity of romantic love in Arthur's kingdom. Through repeated misunderstandings and inadvertent events, Lancelot causes the death of Elaine. In the same way, Guinevere's suspicions of his infidelity are aroused, and for the first time a canker buds in their illicit relationship. In "The Holy Grail,” the quest for the Grail delivers the first mortal wound to Camelot.

King Arthur's vision of the Grail

Through their shallow search for transcendence through worldly adventures, Arthur's knights "follow wandering fires/Lost in the quagmire" (p. 178) as Arthur predicts, and they return to find the neglected kingdom in ruins (p. 107). Too late, they learn from Arthur that spiritual illumination comes not through dramatic revelations, but the performance of everyday responsibilities. As Arthur voices this wisdom, it is plainly Tennyson's version of the Victorian conception of duty:

...the King must guard

That which he rules, and is but the hind

To whom a space of land is given to plow,

Who may not wander from the alloted field

Before his work be done, but, being done.

Let visions of the night or of the day

Come as they will; and many a time they come (pp. 191-2).

However, by this time radical corruption has set into the kingdom, as Tennyson shows in "Pelleas and Ettare," a dark retelling of "Gareth and Aynette." In this version, the gentilesse has run out. Ettare, the Lynette-like petulant maiden, refuses to relent in her distain for Pelleas, who, like Gareth, is an idealistic young knight. As in the previous Idyll, Sir Gawain plays the churl, and it is his lust that shocks Pelleas into gross revulsion for the hypocrisy of the Court, when he discovers the senior knight in the arms of his beloved following their agreement. When Pelleas blunders into Camelot, accusing Lancelot of adultery to his face, there is, unlike the previous tale, no reconciliation, only the young knight's sickened disgust with pervasive social shame (Tennyson's comment on Victorian hypocrisy) and Modred's ominous portent that "The time is hard at hand" (p. 206).

"The Last Tournament" witnesses Camelot in the last stages of decay, to the extent that the infamous Red Knight (who is Pelleas) can inform

...the King and all his liars that I

Have founded my own Round Table in the North,

And whatsoever his own knights have sworn

My knights have sworn the counter to it....

But mine are truer, seeing they profess to be none other (p. 208).

This sweeping inversion of Arthur's principles that has overtaken the kingdom is displayed in the Tournament of Dead Innocence won by Tristram, who in his victory speech praises expedience over honor: "Strength of heart/And might of limb, but mainly use and skill,/And winners in this pastime of our King" (p. 211). Later, Tristram justifies his duplicity with Isolt with what Tennyson makes a definition of modern moral relativism:

The vow that binds too strictly snaps itself—

My knighthood taught me this—ay, being snapt—

We run more counter to the soul thereof

Than had we never sworn (p. 222).

In this speech, Tennyson predicts beautifully the modern argument for the relaxation of moral standards; in Freudian terms, repression stifles and warps the authentic personality. But Tennyson illustrates the ultimate fruits of such an attitude carried to irresponsibility.

In the most abrupt, unsettling ending of any Idyll thus far, Tristram is cut down from behind by Mark, whose treachery matches Arthur's knight's own deceit.

It is in "Guinevere" that Tennyson makes the strongest use of Arthur's identity as a Platonic Ideal. In these terms, Guinevere serves as the Flesh, or Being, or the World, the raw clay the Ideal must mold in order to refashion reality. Before their marriage, Arthur states this symbolic relationship in explicit terms:

But were I join'd with her,

Then might we live together as one life,

And reigning with one will in everything

Have power on this dark land to lighten it,

And power on this dead world to make it live (p. 17).

Guinevere's adultery with Lancelot is, like Cressida's infidelity in Chaucer's Troilus and Cressida, the fickle betrayal of the Ideal by the Flesh of this world with the wavering Real (Lancelot). After Arthur renounces their marriage (since to persist would be hypocrisy in his eyes), he outlines this relationship in these words:

I cannot take thy hand; that too is flesh,

And in the flesh thou hast sinn'd; and mine own flesh,

Here looking down on thine polluted, cries,

"I loathe thee:” yet not less. 0 Guinevere,

....I love thee still (p. 237).

In Pauline language, Arthur is here viewing her fornication as an infidelity of the spirit. His initial reaction is Victorian loathing, which condemns the sins of the flesh above those of the spirit. But Arthur's ingrained Christianity, which recognizes that the opposite is true, overcomes his cultural conditioning and permits him to love her still as something necessary to him. Arthur's farewell voices his faith in the Christian neo-Platonic afterworld, where

Hereafter in that world where all are pure

We two may meet before high God, and thou

Wilt spring to me, and claim me thine, and know

I am thine husband—not a smaller soul,

Nor Lancelot, nor another. Leave me that,

I charge thee, my last hope (p. 238).

Eleanor Roosevelt, the great American idealist: isn't she beautiful?

It is only Arthur's hope of an otherworldly reconciliation and spiritual union that saves Guinevere from suicidal despair and guilt. In a gradual revelation, she comes to recognize the true value of Arthur's love (the Ideal) over the sensual pleasure of Lancelot's (the Real). Using classic neo-Platonist images, she says she

...half-despised the height

To which I would not or I could not climb—

I thought I could not breathe in that fine air,

That pure severity of perfect light—

I yearn'd for warmth and color which I found

In Lancelot—now I see what thou art,

Thou art the highest and most human too,

Not Lancelot, not another....

It was my duty to have loved the highest....

We needs must love the highest when we see it,

Not Lancelot, not another (pp. 239-40).

The American Lancelot

FDR and Churchill weren't glamorous, and boy were they flawed, but they saved Western civilization from Hitler

Her change of heart is of paramount importance, for as the personification of the Flesh and the World, she stands as the representative of the physical matter that Arthur's idealism longs to re-form. Earlier, her betrayal marked the temporary failure of Arthur's dream; but her reform signals the healing power of Arthur's vision and the increased chance of its eventual victory. The character of the new life she takes up is a clue towards Tennyson's solution of the plight of modern civilization. She becomes a nun. In Tennyson's eyes, significantly enough, her asceticism is composed of good works and introspection (pp. 240-1).

"The Passing of Arthur" sees Arthur at the end of his dream. His lands lie in ruins, and anarchy has resumed. The beast has returned. Yet, even at the last, he refuses to relinquish his faith in visionary idealism. He counsels Bedivere:

...More things are wrought by prayer

Than this world dreams of. Wherefore, let thy voice

Rise like a fountain for me night and day.

For what are men better than sheep or goats

That nourish a blind life within the brain.

If, knowing God, they lift not hands of prayer

Both for themselves and those who call them friend? (p. 251).

In the face of disruption, Arthur maintains that faith must be asserted. In his view, prayer serves not only a religious function, but is constituted of directed hope bolstered by faith. The only faculty that distinguishes us from beasts ("sheep and goats") or that prevents us from falling prey to the wild urges of the subconscious (the "blind life within the brain") is man's gift of will. Through purposeful action, man can impose order on the chaos of existence.

The close of Arthur's dream is one of hope and rebirth. Like the river, Arthur, on his death barge, flows back into the ocean (the continuum of being), later to reappear re-formed, not dead, only invisible for the time being and waiting to make a fresh advent, like the dawning sun of the new day. Thus the apocalyptic closing line of the poem: "And the new sun rose bringing the new year" (p. 253).

Tennyson leaves clear traces of the heritage of Arthur's dream. As Camelot crumbles, Dagonet, Arthur's wise fool, upholds the heroic idealism of his master, who

Conceits himself as God that he can make

Figs out of thistles, silk from bristles, milk

From burning spurge, honey from hornet-combs,

And men from beasts—Long live the king of fools! (p. 215).

Dagonet clearly sees the difficulty inherent in Arthur's enterprise of attempting to institute transcendence in human nature, but through his imagery he glimpses its possibility. Just as God can produce the sweet fruit of the fig from a thorny plant and create delicious honey in the fierce home of the hornet, so can Arthur, as the instrument of God's imminence in the evolutionary process, develop the divine humanity from man's bestiality. Dagonet acknowledges that without doubt men are beasts, but the human dilemma is that such a bestial state is intolerable, and exponents of man's struggle to his higher destiny are to be reverenced. They are the champions of evolutionary progress.

The key motif that underlies the whole of the Idylls of the King is best crystallized in Tennyson's description of "The mighty hall that Merlin built."

Merlin discovers the infant Arthur

In this structure of Arthur's premier artificer and intellect, there are

... four great zones of sculpture set betwixt

With many a mystic symbol, gird the hall;

And in the lowest beasts are slaying men.

And in the second men are slaying beasts,

And on the third are warriors, perfect men,

And on the fourth are men with growing wings....

At sunrise...the people in far fields,

Wasted so often by the heathen hordes,

Behold it, crying, 'We have still a king' (p. 176).

This one masterful allegory embodies the philosophical foundation of the epic. First on the evolutionary scale, man's bestial nature ("beasts") overpowers ("slays") his rational powers ("men"). On the second tier of progress, man's reason fights to overcome his irrational impulses; it is during this age that the epic is set. As a mutant, Arthur represents the first men of the third stage, "warriors, perfect men." In the fourth stage (i.e., Galahad), there is no struggle as in the first two (Whiteheadian process has ceased), and the state of evolutionary rest as enjoyed by the "perfect men" of the third stage (who do nothing, only exist) has passed. His bestial heritage overcome, man is now prepared to fulfill his promise, whose heady freedom, ongoing development, and unlimited range is represented by “growing wings.” The existence of such a manifest plan of evolutionary growth lends joy to the hearts of toiling humanity "in the far fields" of life, beset by chaotic forces, "the heathen hordes." The king celebrated in their cry is the imminence of the plan as represented in the apparent progress around them and in the lives of representatives of the evolutionary process like Arthur.

Tennyson wrote the Idylls of the King to serve the same purpose as Merlin's hall. For his age, assaulted by doubt, despair, wholesale confusion, insecurity, hypocrisy, and cynicism, he labored to construct a lasting monument that, like Merlin's hall, would act as a visible reminder to struggling humankind that its extant progress has only come into being because of continuous effort; only rededicated effort can enable man to fulfill the divine promise visible to us in the gestures of nobility and self-command in forerunners like Arthur. In the character of Arthur, as a representative of the third evolutionary stage, Tennyson presented to us a glimpse of what man could be, of the transcendent greatness of which determined human action is capable.

“You must be the change you want to see in the world,” Gandhi said

Tennyson's greatness lies not only in the overwhelming success of his intent, the flowing beauty of his poetry, and his brilliant use of legendary materials, but most of all in the enduring relevance of his achievement. More than ever, we need to be reminded of Arthur's legacy, in this time of the drastic crisis of confidence that the intelligentsia of the West has been experiencing since 1945, whose seriousness has been growing incrementally since 1963.

Where Arthur advised "prayer"—a willful ordering of sensibility comprised of directed hope bolstered by faith—in the face of fortune's confusion, we have forgotten even to formulate any kind of purposeful attitude that can later be used to orchestrate experience. Instead we have allowed events to overwhelm us, and so the imminence of evolutionary advance escapes us, and such inertia can prove to be fatal, for although imminent, progress is not inevitable. As Tennyson showed, for those of us trapped in the second stage, struggle is still necessary to effect further development, and struggle requires an act of will.

Yet even in the face of such a danger of paralyzing despair as we now face, Tennyson provides a bright glimmer of hope. We must not forget how similar to our own age was the time of anarchy in which Arthur departed as his idealism seemed to fade. To counter the fashionable cynicism of our age, Tennyson thoughtfully included the promise of Arthur's approaching return. For Arthur, and the ascendant spirit of man he represents, is like the sun with which he merges. In its absence, the chaos of night darkness reigns, but in accord with a cosmic schedule, it will return, bringing illumination, and with it the warm stuff of life.

* * * * *

ENDNOTES

Alfred Lord Tennyson. Idylls of the King and a Selection of Poems, ed. by Oscar Williams (New York, 1961), page l01. All page references refer to this edition, the Signet Classic, which unfortunately does not number the lines of the poem.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Tennyson. Alfred Lord. Idylls of the King and a Selection of Poems, ed. by Oscar Williams.

No comments:

Post a Comment