Captain Ahab and His Children: Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, and Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers

The Man Who Wanted World War Three: Another nuclear madman, who constantly tried to provoke an atomic war with Russia in the Fifties

Precious bodily fluids: in Dr. Strangelove, Sterling Hayden's character, General Jack D. Ripper (another terrifying modern-day Ahab), was clearly based on Curtis LeMay, phallic stogie and all

In Captain Ahab, Melville created an enduring American archetype, and subsequent American writers have modeled major characters on Ahab: Jake Barnes in Ernest Hemingway s The Sun Also Rises (1926), General Cummings and Sergeant Croft in Norman Mailer's The Naked and the Dead (l947), and Ray Hicks in Robert Stone's Dog Soldiers (1974).

Captain Ahab finally meets Moby Dick: McCarthy is exposed by his nemesis, righteous attorney Joseph Welch

In fashioning the character of Captain Ahab, Melville was making a series of extremely perceptive observations about the Jacksonian America of his time—the society that, in 1851, was plunging headlong into the fiery abyss of the Civil War—and the trends that Melville observed are still in existence today.

They both went down with the ship: the collapse of the American male ego in the Seventies through drugs, isolation, paranoia, and madness—the Rev. Jim Jones and Howard Hughes did exactly the same thing

What was President George W. Bush doing in goading this nation into a heedless, ill-prepared, and wholly unnecessary war with

What was Adolf Hitler but a German Captain Ahab, leading his nation to utter self-destruction?

I originally wrote an earlier version of this essay as my second Junior Paper in the first semester of my junior year at

Ironically, since I wrote this essay, the name of “Starbuck” has taken on a new and very different connotation. Most customers who troop into a tributary of the world’s biggest coffeeshop franchise fail to realize that Starbuck’s takes its name from Ahab’s courageous Quaker first mate. Starbuck is only member of the Pequod’s crew who has the guts to confront Ahab over the insanity of his hunt for Mocha Dick—but Ahab forces him to cower by turning a blunderbuss on him, just as Sergeant Croft turns an M-1 on Red Valsen, Mailer’s Starbuck in The Naked and the Dead, to force him to back down, and just as Ray Hicks turns a gun on Converse, Stone’s Starbuck in Dog Soldiers, to intimidate him.

Why did Reagan lay wreaths at the graves of SS men in Bitburg in 1985? Who did it benefit? It only helped the Nazis

There’s no dishonor in that—in 2004, decorated Vietnam War hero John Kerry had the gun turned on him by George W. Bush (via the Swift Boaters) when he was accused of lying about his heroic war record, and Dan Rather had the gun turned on him by Karl Rove via a very vicious political ruse on 60 Minutes; through a Rove agent, Rather was fed slightly altered documents that told essentially a true story about Bush’s cowardice in the Vietnam War. Because Rather was so disgraced for broadcasting a story based on a document with stylistic irregularities (using the wrong kind of typewriter), the explosive story of Bush's draft evasion (which is true) is now considered totally taboo by the national media. The fact that both of these brave men, like Starbuck, flinched so visibly in public has banished them from American public life forever, for all intents and purposes.

I wish this essay had become outdated in the 30 years since I wrote it (right after America’s defeat in Vietnam, another example of doomed Ahabism), but as recent events in Iraq have attested, we’re still following Captain Ahab blindly, over the edge of the world. God help us.

* * * * *

"All Greatness is But Disease": Ahab As a Tragic Hero and Ahabism and Its Implications

In writing Moby-Dick, Herman Melville sought to create an epic, complete with tragic hero. But being well versed in Shakespearian tragedy, all of whose heroes are of noble blood, he was faced with the problem of creating a tragic hero in an age in which aristocracy was dead. Through the character of Ahab, Melville exploited his dilemma in such a way that it satisfied his needs. Ahab is the tragic hero of the new Romantic age that came into being after the American and French Revolutions, the modern age whose consequences were just becoming visible.

Melville was clearly aware of this new age; in the chapter, "The Mast-Head," he points out that with the death of the medieval concept of the divine right of kings in his day, the heroes that are idolized are popular actors in great military and political events, such as Napoleon, Washington, and Nelson, whose names crop up constantly throughout the book. (1) Ahab is Man freed from God and free to pursue his own existential concerns.

Ahab's tragedy, as Melville recognizes it, is that his self-destruction is inevitable under the circumstances under which he is placed. As a dedicated Romantic egotist in tune with his time, Ahab is unable to accept the treacheries and injustices of life, symbolized by the loss of his leg in the jaws of Moby Dick, and he cannot blindly accept the authority of God. As a result, out of a very human anger and thirst for revenge, he must hunt down Moby Dick, the symbol upon which he has imposed his rage, to his eventual self-destruction.

Melville recognized that Ahab’s charismatic, self-destructive style of leadership would have universal appeal throughout the world. Referring to Anacharsis Clootz, the French revolutionary and self-styled Orator of the Human Race who proclaimed himself to be the citizen of no single nation but rather a Citizen of the World, Melville describes the Pequod’s international crew as an "Anacharsis Clootz deputation from all the isles of the sea, and all the ends of the earth, accompanying Old Ahab in the Pequod to lay the world's grievances before the bar from which not very many of them ever come back" (p. 166). Queegqueg, drawn from his South Sea island home by the lure of Christianity and the West, drifts aboard the Pequod and is drawn into Ahab’s cause quite willingly, even when he later senses that it will cause his death—which he accepts.

Melville certainly recognized the seeds of Ahabism in the main intellectual currents of his time, particularly in the thought of Emerson, who, as Walter Kaufmann has shown, was a great inspiration to Nietzsche. Later Nietzsche exerted an amazing influence on some of the leading thinkers and artists of the twentieth century, the century of Ahabism par excellance. (2) In "Self-Reliance," which Melville undoubtedly read, Emerson delivers an outburst that could have been pronounced by Ahab on the deck of the Pequod:

The populace think that your rejection of popular standards is a rejection of all standard, and mere antinomianism; and the bold sensualist will use the name of philosophy to gild his crimes. But the law of consciousness abides.... I have my own stern claims and perfect circle. It denies the name of duty to many offices that are called duties. But if I can discharge its debts it enables me to dispense with the popular code. If any one imagines that this law is lax, let him keep its commandments one day. And truly it demands something godlike in him who has cast off the common motives of humanity and has ventured to trust himself for a taskmaster. High be his heart, faithful his will, clear his sight, that he may in good earnest be doctrine, society, law, to himself, that a simple purpose be to him as strong as iron necessity is to others! (3)

The danger of such thinking, which jolted Melville so, is of course the simple fact that no man can presume to be a god and a law unto himself. Thus, Melville identified as the source of tragedy hubris, as did the ancient Greek dramatists. Like Emerson, Ahab is aware of this danger, which he labels "my madness," (p. 226), but he ignores it because only his quest can satisfy his pathological needs. His awareness of his moral trespass and his rejection of the responsibility his awareness entails is the sin for which he must be crushed.

Melville informs us of the forces that shape Ahab's psychological makeup in Ishmael's first description of him. Ostensibly Ishmael is speaking of Captains Peleg and Bildad, but in actually he is referring to Ahab. He says:

So that there are instances among them of men, who, named with Scripture names—a singularly common fashion on the island—and in childhood naturally imbibing the stately dramatic thee and thou of the Quaker idiom; still, from the audacious, daring, and boundless adventure of their subsequent lives, strangely blend with these unoutgrown peculiarities, a thousand bold dashes of character, not unworthy a Scandinavian sea-king, or a poetical Pagan Roman. And when these things unite in a man of greatly superior natural force, with a globular brain and ponderous heart; who has also by the stillness and seclusion of many long night-watches in the remotest waters, and beneath constellations never seen here at the north, been led to think untraditionally and independently; receiving all nature's sweet or savage impressions from her own virgin voluntary and confiding breast, and thereby chiefly, but with some help from accidental advantages, to learn a bold and nervous lofty language—that man makes one in a whole nation's census—a mighty pageant creature, formed for noble tragedies. Nor will it at all detract from him, dramatically regarded, if either by birth or other circumstances, he have what seems a half willful overruling morbidness at the bottom of his nature. For all men tragically great are made so through a certain morbidness. Be sure of this, 0 young ambition, all mortal greatness is but disease. (pp. 111-112)

Here Melville is asserting that Ahab is product of both his environment and his natural psychological inclinations. Ahab is a man born into a Christian society and inculcated with its values (represented by the "Scripture names" and "the stately dramatic thee and thou of the Quaker idiom"), including extreme moral perfectionism dangerously reinforced with an apocalyptic mind-set—and apocalyptic longings. This society, America, is an island; and the beginning of the book, which is set on land, Ishmael constantly reminds us how the citizens of New Bedford derive everything for their daily lives from the sea.

As citizens of Island America and the New England fishing community, Ahab and those like him are raised is an insular environment cut off from any tempering influences. Combined with this absolutist socialization process is Ahab's own personality, a strong mind sensitive to and overwhelmed by its surroundings, until, so immersed in itself, it is warped into monomaniacal compulsion.

Through his final line, "Be sure of this, O young ambition, all mortal greatness is but disease," Melville is warning all incipient Ahabs that all "mortal" pursuits—fashioned and carried out entirely in a perspective that fails to take into account a higher power beyond one's control (whether God or social, psychological, and historical forces)—are doomed to disastrous failure, because of the tunnel vision the quest induces.

Yet Ishmael labels such an undertaking "great" and "noble." His description of Ahab expresses his own Romantic longings for a hero who will rebel against the forces that he feels are trapping him. As he declares, early in the book:

Though I cannot tell why it was exactly that those stage managers,--the Fates, put me down for this shabby part of a whaling voyage, when others were set down for

magnificent parts in high tragedies….

Chief among these motives was the overwhelming idea of the great whale himself. (p. 29)

Also, Ishmael can identify with Ahab. Admitting in the first chapter, "Loomings," that he goes to sea to escape his suicidal and violent impulses, he states that he feels tolerance for what he sees as the irrational in others "for we are all somehow dreadfully cracked about the head, and sadly need mending" (p. 121). Thus he sympathizes with Ahab’s dementia. Even Starbuck feels that Ahab is fulfilling a drive that he himself dares not admit: "For in his eyes I read some lurid woe would shrivel me up, had I it" (p. 228). Referring to Queegqueg's worship, Ishmael says, "Now, as I before hinted, I have no objection to any person's religion, be what it may, so long as that person does not kill or insult any other person, because that person don't believe it also" (p. 124).

But he is unable to resist Ahab's dangerous fanaticism because of his easy-going moral relativism, which fails to supply him with strong convictions. For Ishmael the isolato, without friends or family or any sort of emotional relationship, security is found in escape, in the mast-head, where

a sublime uneventfulness invests you; you hear no news; read no gazettes; extras with startling accounts of commonplaces never delude you into unnecessary excitedness; you hear of no domestic afflictions; bankrupt securities; fall of stocks; are never troubled with the thought of what you shall have for dinner—for all your meals for three years and mote are snugly stowed in casks, and your bill of fare is immutable. (pp. 209-10)

As a natural leader, Ahab senses this lack of resistance and hunger for a Fuehrerprinzip on the part of his crew of isolatoes, and he manipulates these forces to win over the crew. He employs obvious dramatics, not revealing himself at first and gazing out at the sea moodily to create an air of mystery about himself, which the crew responds to.

This is the same air of mystery that in part attracts Ahab to Moby Dick.

"Moby Dick," by the great doomed Abstract Expressionist painter Jackson Pollock--yet another tragically self-destructive Ahab

To further this sense of mystery, he nails the doubloon and performs the mystical rite of baptism upon the harpoons, and as a demagogue, he utilizes rhetoric to sway the already-susceptible crew to his cause.

It is this conscious manipulation that compounds his crime. Even worse, he admits he is not entirely certain of the validity of his crusade. Describing Moby Dick as a symbol that masks ultimate reality, he says, "If a man will strike, strike through the mask! How can the prisoner reach outside except by thrusting through the wall? To me, the white whale is that wall, shoved near to me. Sometimes I think there's naught beyond," he confesses, then hastily adds, "But 'tis enough" (pp. 220-1).

Ahab is conscious of his duplicity and the dubiety of his quest, yet he leads the men to what he knows might be their doom; and the crew lets him. Starbuck objects that Moby Dick is no devil incarnate, only a brute beast, and that the injury he inflicted on Ahab was an accident (one, incidentally, Ahab should have expected, chasing the whale), not part of some malignant design. But Ahab overcomes Starbuck's rational argument by appealing to his irrational suspicions (instilled by the Puritan vestiges of American society that the two men share) that earthly existence only cloaks a transcendental reality; and so Ahab captures the crew.

During this scene, Ishmael notices how

he stood for an instant searchingly eyeing every man of his crew. But those wild eyes met him, as the bloodshot eyes of the prairie wolves meet the eye of their leader, ere he rushes on at their head in the trail of the bison; but, alas! only to fall into the

Ishmael is prophetic; the adventure of these conquistadores venturing into uncharted moral territories proves a horrendous disaster, as Moby Dick annihilates Ahab, the Pequod, and all its crew except Ishmael. In this case, "the Indian" that traps them is, according to one's interpretation, either Father Mapple's punishing God, or the social, psychological, and historical forces that have overtaken Ahab and the crew.

As a Puritan divine, Father Mapple provides a valuable moral compass in the book. In his famous sermon, he describes Ahab indirectly.

Delight is to him—a far, far upward, and inward delight—who against the proud gods and commodores of this earth, ever stands forth his own inexorable self. Delight is to him whose strong arms yet support him, when the ship of this base treacherous world has gone down beneath him. Delight is to him, who gives no quarter in the truth, and kills, burns, and destroys all sin though he pluck it out from under the robes of Senators and Judges. (p. 80)

In many ways, Father Mapple's sermon serves as the key to the novel, and by the end of the book, Ishmael has learned its significance, or at least so we are led to believe. Ahab is the Puritan spiritual leader who is the warrior of his God of the second half of the sermon. He, like the Puritans, needs to moderate his irrational perfectionism and absolutism; and like Father Mapple's warrior, he does not outlast the lifetime of his God. Like Jonah in the first half of the sermon, Ishmael has his life spared from disaster, he believes for the purpose of warning us: "And I only am escape alone to tell thee," he quotes from Job (p. 723).

However, unlike Ishmael, he is not absolutely certain that he was rescued by God; his survival may be an accident. Yet at the time when he is writing the book we are reading (for, a s awork of fiction, Moby-Dick is supposed to be his autobiographical account of his remarkable voyage), we know he is attempting to make some sense of the astounding experience he has just survived, in order to warn us of the lethal perils of such a course. His bitter experience has taught him to deal no longer in absolutism and to resist the appeal of fanatical leaders, and we feel that he, with his gentle humor, kindness, tolerance, and easy-going nature, just might have been spared because of all the crew, he was the best equipped to carry on for the future.

There is no doubt that Melville succeeded in his aim of creating a tragic hero commensurate with the modern age. Ahab, without God, and so consumed by his egotism, is tragic because he is fully aware of the implications and consequences of his sins, and yet he cannot resist his self-destructive impulses because they fill and define his existence, and they are too strong for him to resist.

One can criticize Moby Dick on the grounds that it lacks fidelity to the reality of American life, because Ahab and his fate are too glorious and heroic. The two Americans in recent public life most like Ahab, Joseph McCarthy and Richard Nixon, suffered disgrace and eventual obscurity after their self-destruction, as they wondered all the time what had had happened to them. To this can only be said that Melville was writing in symbols and that Ahab did not die in a blaze of glory, but was crushed and drowned by the White Whale.

As for Ahab's self-awareness, which can be said to be lacking in his real-life counterparts, Melville created it to elevate his character to a tragic stature. As we learned from Vietnam, psychopathic killers like Lieutenant Calley (and torturers like Lyddie England in Iraq) are blind to the meaning of their actions. Without tragic self-awareness, they lack any consciousness of the implications of their moral decisions. That’s to our detriment. Deep down inside, Ahab knew that what he was doing was wrong. But can a blind killer stop himself?

Appendix: The Children of Ahab

"So good-bye to thee—and wrong not Captain Ahab, because he happens to have a wicked name. Besides, my boy, he has a wife—not three voyages wedded—a sweet, resigned girl. Think of that; by that sweet girl that old man has a child; hold ye then there can be any utter, hopeless harm in Ahab? No, no, my lad; stricken, blasted, if he be, Ahab has his humanities!"

So Peleg informs Ishmael (p. 120). When examining the docked ships at the wharf at New Bedford, Ishmael muses "that one most perilous and long voyage ended, only begins a second; and a second ended, only begins a third, and so on, for ever and aye" (p. 93). Therefore, Ishmael knows that unless Americans change, the pattern of Ahab leading the crew (symbolizing society) to destruction, will be repeated indefinitely.

If American literature is to be trusted, wars seem to create Ahabs, or at least bring them to the surface. This is not surprising, since Moby-Dick is often interpreted as a prefiguration of the Civil War (America destroying itself in an orgy of irrational self-destruction) and Ahab as seen as a symbol of the intractable, fanatical leaders (like John Brown and fanatical Southerners) who blindly led America into the Civil War. Wars occasion the appearance of characters like Ahab in three later works of American literature: the First World War in Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (1926), the Second World War in Norman Mailer's The Naked and the Dead (l947), and Vietnam in Robert Stone's Dog Soldiers (1974).

Isn't it pretty to think so?: a shattered Jake Barnes (Tyrone Power) commiserates with Lady Brett (Ava Gardner)

In The Sun Also Rises, Jake Barnes is like Ahab in that where Moby Dick, representing the impersonal forces of life, bit off Ahab's leg, the First World War severed Jake's penis. In the following passage from The Eternal Adam in the New World Garden, David W. Noble is referring to Hemingway, but what he says applies just as directly to Jake:

It is perhaps not too imaginative to hear him cry out to Melville's Ahab for forgiveness because he does not have the courage to continue the struggle. Like Nick and Fredrick, he had been wounded too desperately to renew the battle against the implacable forces of the universe. Ahab sought out death in his vain ambition to conquer it, and Hemingway, the child of Ahab, remains loyal to the father's vision although he knows from the fate of the elder that the dream of perfection can never be fulfilled. All he can do is preserve the dream in his own heart by surviving as an impotent innocent. As long as he lives, he will remain a Puritan. (4)

Yet another tragic Ahab: the doomed sailor who wrote the Moby-Dick of the Fifties, The Old Man and the Sea

The Naked and the Dead features two Ahabs. General Cummings, the intellectual Ahab, seeks to conquer the island of Anopopei, held by the Japanese in the Pacific; Sergeant Croft, the Ahab of direct action, on a correspondingly smaller but more direct scale as a platoon leader, wants to climb Mount Anaka.

Sergeant Croft (Aldo Ray), the WW II Ahab in the field, and his Ishmael Lt. Hearn (Cliff Robertson)

General Cummings, influenced by the power morality of Nietzsche and Spengler, is a fascist thinker of the Lawrence Dennis stripe who serves as Mailer's Grand Inquisitor, making statements such as, "The natural role of twentieth-century man is anxiety," "You're a fool if you don't realize this is going to be the reactionary's century, perhaps their thousand-year reign," and, "You know, if there is a God, Robert, he's just like me," to Lieutenant Hearn, the Harvard liberal who is Mailer’s synthesis of Ishmael and Starbuck. Hearn’s fascination with Cummings could have been voiced by either of Ahab's foils:

And he couldn't escape the peculiar magnetism of the General, a magnetism derived from all the connotations of the General’s power. He had known men who thought like the General; he had even known one or two who were far more profound. But the difference was that they did nothing or the results of their actions were lost to them, and they functioned in the busy complex mangle, the choked vacuum of American life. The

The fascist General Cummings (Raymond Massey), clearly based on another Ahab, Douglas MacArthur: Mailer has stated openly that he modeled The Naked and the Dead on Moby-Dick

Later, when Cummings transfers Hearn to lead a reconnaissance patrol on the other side of the Island, Croft, the platoon leader, is seized with a blindly unconscious urge to prove his mastery over existence by scaling Mount Anaka.

The contest seemed an infinite distance away, and he felt a thrill of anticipation at the thought that by the following night they might be on the peak. Again, he felt a crude ecstasy. He could not have given the reason, but the mountain tormented him, beckoned him, held an answer to something he wanted. It was so pure, so austere. (9)

Fearing of a postwar tide of domestic anti-Communism, Hearn decides to take political action after the war to stop the triumph of Cummings' brutal power philosophy. But when he vetoes a climb of the mountain, Croft arranges it so he walks into a lethal Japanese ambush unawares. Now in command of the patrol, a cross-section of American society, Croft drives the men ruthlessly up Mount Anaka.

On the verge of exhaustion, Red, like Starbuck, rebels and tries to convince the other men of the insanity of Croft's mission so they will refuse to continue, but Croft aims his rifle at them and tells them any who have a strong enough conviction to stop him can sacrifice their lives. "Who wants it first?" he says. Defeated, the men plod on. Just before they reach the summit, however, nature, in the form of a hornet's nest, frustrates Croft by attacking the patrol, and the men run howling down the slope. Later:

Goldstein told Croft how they had lost Wilson, and was surprised when they made no comment. But Croft was bothered by something else. Deep inside himself, Croft

"For that afternoon at least..." In another form, Croft's monomaniacal impulses will awaken later. As for the men, Mailer makes it clear in the succeeding chapters that they have not learned at all from their experience. Hearn the idealist is dead, and Cummings is left planning for the anti-Communist crusade to come at home.

There would be few Americans who would understand the contradiction of the period to come. The route to control could best masquerade under a conservative liberalism. The reactionaries and isolationists would miss the bell, cause almost as much annoyance as they were worth. Cummings shrugged. If he had another opportunity he would make better use of it. What frustrations! To know so much and be hog-tied.

To divert his balked nerves, he carried out the mopping-up with a ceaseless concentration on details. (11)

"The mopping-up” is a euphemism for the American massacre of the remaining Japanese troops.

In Dog Soldiers, Robert Stone's novel of the domestic consequences of Vietnam set in 1971, Ray Hicks, an ex-Marine veteran of Vietnam, could well be a demobilized Croft one generation later. A psychopath who has discovered Nietzsche and Zen, Hicks agrees to smuggle heroin into the States as a favor for his friend Converse, a playwright, now a journalist in Vietnam, who undertakes the smuggling as an existential gratuitous act. In California, Hicks meets Marge, Converse's wife, and while he is seducing her, she recognizes Hicks as, like Ahab, the personification of the id:

He had a hungry face; in it Marge detected a morphology she recognized. The bones wore strong and the features spare but the lips were large and frequently in motion, twisting, pursed, compressing, being gnawed.

Deprivation—of love, of mother's milk, of calcium, of God knows what. This one was sunburned, usually they were pale. They always had cold eyes. They hated women.

....His eyes seemed as flat as a snake's. There was such coldness, such cruelty in his face that she could not think of him as a man at all. (12)

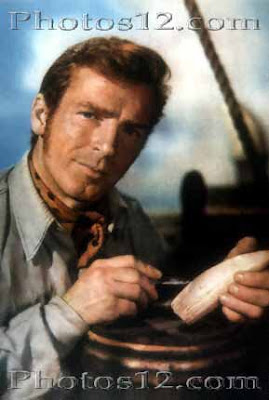

Nick Nolte as Ray Hicks in the film version of Dog Soldiers, Who'll Stop The Rain (1978), screenplay by Robert Stone

When a pair of corrupt narcotics agents raid Marge's home, Hicks beats them, ties them up and leaves with Marge and Janey, Marge's small daughter, dropping Janey off with a stewardess friend of his. From there they flee the authorities along the West Coast. By this point, Marge is already abusing tranquillizers heavily, but in a seaside bungalow, Hicks introduces her to the heroin he is carrying for her husband, ostensibly to calm her jangled nerves.

Robert Stone, a Navy veteran and experienced sailor

While she is helpless under the influence of heroin, he goes outside, feeling the impulse to desert her right then and there. The process by which he reaches his decision whether to stay or go is recorded in the following passage, which shows a striking similarity to Ahab's exhortation to the crew of the Pequod. Hicks thinks:

In the end there were not many things worth wanting—for the serious man, the samurai. But there were some. In the end, if the serious man is still bound to illusion, he selects the worthiest illusion and takes a stand. The illusion might be of waiting for one woman

If I walk away from this, he thought, I'll be an old man—all ghosts and hangovers and mellow recollections. Fuck it, he thought, follow the blood. This is the one. This is the one to ride till it crashes. (13)

Hicks' psychopathic insanity emerges when he makes a deal with a Hollywood friend named Eddie Peace to unload the heroin. After Eddie refuses to passively accept Hicks' attempt to intimidate him, Hicks, in revenge, delivers a lethal overdose to Gerald, a writer Eddie brought to buy the drugs.

Hicks and Marge speed away from the motel where Eddie is left with the dying Gerald and his hysterical wife, and the following exchange between Hicks and Marge presents the flavor of Hicks' mind:

Marge was crying again.

"I can't hack it," she explained, "it's too much."

"You're doing fine."

They followed the coast highway south past Santa Monica and the arcades of Venice.

"So why Gerald?"

"Because he's a Martian. They're all Martians."

"What are you?"

"I'm a Christian American who fought for my flag. I don't take shit from Martians."

"My God," Marge said, trying to keep the tears out of her voice, "you killed the man."

"Maybe."

"He was just a jerk with a dumb idea." She stared at the merciless eyes, trying to see him again, trying to make him be there. "The same as us."

"Peace was fucking me. He was fucking me bad."

"Last week we were ready to throw the shit away,"

"He hit me," Hicks said.

"He hit you?" Her voice rose to an incredulous whine she could not control. "Are you three years old?"

"I was drunk. It seemed like a good idea."

Marge tried to experience Gerald’s overdose as a good idea. It was not the way she was used to looking at things.

"So fuck Gerald?"

"That s right," Hicks said. "Fuck Gerald."

"For all the obvious reasons."

"Fuck all the obvious reasons."

Feeling indifferent to Gerald made Marge cold. She put her sweater on.

"I should have done up when I had the chance,"

"Hue City," Hicks said. "We had guys there who were dead the day they hit that place, in the morning they were in Hawaii, in the afternoon they were dead. I had six buddies shot to shit in Hue City in one morning."

"I quit," Marge said. "Fuck Gerald." (14)

Hicks and Marge (Tuesday Weld) on the run

When Converse returns to America, he is picked up by the narcotics agents and tortured, and Marge becomes totally addicted. At the end of the book, Hicks is seriously wounded in a Vietnam-style firefight in a California forest with the agents. He manages to crawl away with a knapsack filled with the heroin, and with incredible insane endurance, makes a trek across the desert (like Frank Norris' McTeague) until he collapses and bleeds to death.

Meanwhile, Converse has found Marge, and together they evade the agents. After driving through the desert and discovering Hicks' body, Converse arrives at the realization that his relationship with his wife is now ruined, because of the Conradian chain of events he triggered, and most of all, because of her experience with Hicks.

"In the worst of times," he began to tell her, "there's something."

"Ha," Marge said. "There's smack." She watched him pace in bewilderment. " In the worst of times there's something? What?"

"There's us."

Marge laughed.

"Us? You and me? That's something?"

"Everybody," Converse said. "You know."

"Sure," Marge said, "that's why it's so shitty. (15)

At the end of the book, there is a car chase where the agents pursue Converse and Marge across the desert, and Converse realizes he was set up by his Saigon dealer, an American woman named Charmane who's working with the CIA and the Nixon Administration to funnel heroin into the United States for profit. Finally he understands that he was tricked into smuggling the heroin just so Charmane and her Washington associates could hijack his skag and keep it for themselves. (See The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia by Alfred J. McCloy and Donald Freed's accusation in his play Secret Honor that Nixon actually resigned because during the Watergate investigation, H. Wright Patman's House Banking Committee traced Asian checks deposited to the account of the Committee to Re-Elect the President after the election to Saigon heroin lords who were personally paying off Nixon over a million dollars a year to perpetuate the Vietnam War to insure the uninterrupted flow of heroin to the coffers of the CIA and organized crime. Significantly enough, Nixon never sued Freed, even after Robert Altman made a film of Secret Honor in 1984 containing this most shocking accusation.)

During the climactic car chase, we can see the disintegration Marge has suffered and the total fatalism to which Converse has been reduced, not only because of Hicks' dynamic evil, but also because of Converse's nihilism.

When Converse sees the pursuing car in the rearview mirror:

Marge leaned over to where she could see the mirror, turned to look behind them, then turned back to the mirror again. Her face flushed, her eyes grew wide.

"Oh God," she cried. A burst of spitty laughter broke over her lips. "Oh my God, look at it."

She leaned out of the window and screamed back at the column.

"Fuck you," she shouted. "Fuck you—fuck you."

When they reached the road again, the column had settled, the thing had stopped. There were still no cars in sight.

"Let it be," Converse said. (16)

The comparison to the flight of Lot and his wife from the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah is clear. The couple escape, but to worse than nothing.

The nuances of their conclusions may differ—the bitterness Hemingway finds is not the grinding brutality Mailer sees or the horror Stone uncovers—but all of these three writers who have dissected the children of Ahab agree that these vessels of crushed hopes and dreams, raised in an emotionally sterile society, will institute a nightmare as they impose their rage on those around them, who will acquiese out of weakness.

The children of Ahab may lack his tragic stature, but their ignorance of the forces driving them make the wreckage they create all the more terrible. With each generation, American writers confirm Melville's dark vision of destruction, and if the past (according to Hemingway and Mailer) and the present (as Stone sees it) are any indication, unless Americans change themselves, the future will turn out to be the same, and America will march further down the road to irrevocable self-destruction.

* * * * *

ENDNOTES

- Herman Melville, Moby-Dick, ed. Charles Feidelson, Jr. (New York, 1964), p. 208. All page references are from this edition.

- See Walter Kaufmann, Nietzsche (Princeton, 1973).

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Selected Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, ed. Brooks Atkinson (New York, 1930), p. 161.

- David W. Noble, The Eternal Adam in the New World Garden (New York, 1968), p. 152.

- Norman Mailer, The.Naked and the Dead (New York, 1947), p. 140.

- Ibid., p. 68.

- Ibid., p. 145.

- Ibid., p. 68-9.

- Ibid., p. 387.

- Ibid., p. 546.

- Ibid., p. 556.

- Robert Stone, Dog Soldiers (New York, 1974). p. 95.

- Ibid., p. 168.

- Ibid., p. 202-3.

- Ibid., pp. 336-7.

- Ibid., pp. 338.

An extremely rare first edition

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bowen, Merlin. The Long Encounter.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. The Selected Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, ed. Brooks Atkinson.

Franklin, H. Bruce. The Wake of the Gods. Stanford, 1963.

Hemingway, Ernest. The Sun Also Rises. New xork, 19$4.

Kaufmann, Waiter. Nietzsche.

Levin, Harry. The Power of Blackness.

Mailer, Norman. The Naked and the Dead,

Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick, ed. Charles Feidelson, Jr. New York. 1964.

Noble, David W. The Eternal Adam in the

Parker, Hershel, and Harrison Hayford, eds. Moby-Dick as Doubloon.

Seltzer, Leon F. The Vision of Melville and Conrad.

Stone, Robert. Dog Soldiers.

Thompson, Lawrance. Melville's Quarrel With God.

Vincent, Howard P. The Trying-Out of Moby-Dick.

No comments:

Post a Comment