Every action has an equal and opposite reaction, and such was the case the night of April 12, 1976, when as a young writer and a junior at Princeton one month shy of my twenty-first birthday, I heard esteemed novelist and critic William H. Gass absolve writers of any responsibility for the words they use. At the end of his lecture, I was rocketing up out of my seat and I knew I had to write this essay.

Writers have no responsibility for the words they use? Then it was essentially okay for a writer to channel the sensibility of Reinhardt Heidrich? This essay poured out of my typewriter at white-hot heat that night.

Don't get me wrong: Bill Gass is a brilliant, first-rate American writer, and I have the greatest respect for him and his amazing body of work. But his provocative statements that night seemed so extreme that I felt I just had to respond.

This article was the first thing I ever wrote that I thought showed serious promise, and it was published in the April 25, 1976 issue of The Princeton Forerunner, which at the time was a brand-new alternative campus newspaper that had just sprung up at Princeton, kind of a Village Voice to The Daily Princetonian’s New York Times. It didn’t last long, but there was a young editor (whose name escapes me) who did a terrific job of cutting down my piece.

I still stand by what I said in this article, and it’s the closest thing to an artistic and creative credo I’ve ever formulated.

My thanks to Mr. Gass for forcing me to assess what I really think the artist's role in society is. I guess that's what he wanted me to do as a result of his lecture that night—provoke me to think.

Art For Life's Sake

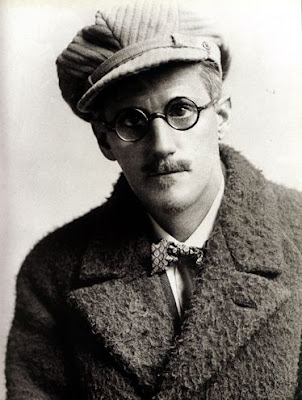

Two weeks ago, on the evening of Monday, April 12, William H. Gass, professor of philosophy at Washington University, delivered this year's Rabbi Irving M. Levey lecture, entitled "Carrots, Nose, Snow, Rose, Roses: The Ontological Transformation of Language and Literature." Although little known to the general public, Gass is considered one of the foremost writers in

The fact that he is one of the judges of this year's National Book Award gives added weight to his well-chosen words of April 12. His lecture, and the enthusiastic response it drew, indicates the present direction of American literature and literary criticism.

His central metaphor was that of a snowman. When we build a snowman, we take carrots, lumps of coal, and old woolen mufflers and overshoes out of their quotidian context (that of practical use in our hands) and place them in a wholly fresh one. On a snowman a carrot becomes a nose. We accept it as a nose; we don't think of eating it. As Gass said, this is an ontological transformation.

Gass then applied the same standards to words. In daily conversation, we use words for purely practical purposes—for communication, for self-expression, for getting what we want. We interpret words used in public seriously; if someone tells us, "I hate you," we assume they mean it. We make moral judgments on the way people use words.

But according to Gass, when words are used for a literary purpose, they are suddenly absolved from moral accountability. They need have no rational relation to the outside world, because they have been placed in a different context. Literature does not have to apply to life. On a snowman we accept the carrot as a nose placed in a different context. Literature does not have to apply to life. On a snowman we accept the carrot as a nose and don't think of eating it, right?

The analogy between carrots and words is, of course, a fallacy. A carrot is different from a word. Building snowmen is not the same as writing a novel. Snowmen exist to amuse us. Words exist to enable us to communicate. If I am used to interpreting a word one way when it is used in daily speech and the mass media, I will naturally apply the same interpretation to that word if I encounter it in a work of literature. The same applies to complexes of words, known as ideas. I will identify the anti-Semitism of Ezra Pound's Canto XLV ("With Usura") as the same sentiment upheld in Mein Kampf. Pound's and T.S. Eliot's anti-Semitism expressed in their poetry does not carry a different meaning just because those men were great poets. Being a creator of literature does not absolve one from moral responsibility.

Gass believes otherwise. In his lecture he declared, "Physics, philosophy, and poetry are not bound by moral considerations. They should have no end but themselves." It astounds me that any intelligent person in this century could make that statement. Physics is not bound by moral responsibility? J. Robert Oppenheimer believed very deeply in that responsibility; on witnessing the world's first atomic explosion, he realized that now, like

This is nihilism of the purest sort. It is not only an ivory-tower view; it is a conscious abdication of moral responsibility. As critic John Leonard has written, "I am astonished that we are all prepared to insist on the moral obligations of the nuclear physicist, the cabinet member, the university president, the sociologist on government contract, the director of General Motors, the construction worker and the newspaper editor, and yet we foist upon art an autonomy as if it had been dropped on us from Mars... Without going quite so far as Samuel Butler, who suggested that, 'Books should be judged by a judge and jury as though they were crimes,' I'd say that either we relate our profession to the world we live in or we have no more ethics than a can of Spam."

Writers are supposed to be more than the fathers of pleasant artifacts; they are supposed to be thinkers. Indeed, they should consider very carefully the connotations of every word they employ. That is where words differ from carrots.

Carrots are blank physical entities; one can interpret them as one wishes, as resembling a nose, icicle, phallus, or rocket. The power of a word is derived from the meaning agreed upon by its users. A carrot can suggest whatever you want, but when you use a word, you are making a statement, and it doesn't matter whether you make it in a conversation or a poem or a novel; the word still carries the same meaning and the same moral weight. When Henry Miller tells me in Tropic of Cancer that since the world is destroying itself, he'll look out for himself, full speed ahead and the devil take the hindmost, I don't think, "How droll!" I think Miller is copping out.

I think Gass is copping out too. At the conclusion of his lecture, he could see no reason why art should have anything to do with what he called "the sweaty standards" of the world we live in, and he urged all artists to enjoy their private act of creation before returning to their "less-real rooms." He ended his lecture as he began, with the metaphor of the snowman; only this time, he called upon us to build bigger and better snowmen (metaphors for morally autonomous creation) using not only coal and carrots, but also raiding our homes and adding our grand pianos and family portraits to the growing snowball, until we had fashioned a monster snowman; in other words, he wants us to ignore the reality of daily life in order to create works of art.

(This is known as The Eugene O'Neill Method, and it has its problems. Worship the Muse to the exclusion of your family. And if your kids bother you? Tell them to get the hell out of your household and never come back. Unfortunately, as a result, one of his sons turned to heroin. Tough. Well, at least we have those beautiful plays, right?)

With the arrival of spring, the snowman will melt, of course, Gass said. He went on to pose the question: But afterwards won't our grand piano be ruined? (After the glow of artistic creation fades, won't we suffer from having neglected our everyday responsibilities?) Gass answered, voice oozing sarcastic concern: "What a shame, what a pity." Long pause as he scanned the audience. "What a loss."

Riotous applause.

It upset me. Here he was, asking writers to abandon their moral responsibility and appealing to us to cast our lot with an illusory imaginative construct (a ball of snow, in fact) that was sure to vanish, and allaying our fears by remarking that really the loss of reality (in the form of the snow-damaged piano) was not as important as we might think, and by their applause this audience of intellectuals was showing its approval. Gass is an impressive lecturer, extremely articulate and very witty, but consonant with the artistic preachment of his argument, his lecture was all style and no substance.

For those who follow the course of modern literature, the gist of Gass' lecture will come as no surprise. Scholars of modernist writing have long praised what they see as its detachment from the concerns of realistic fiction, that of making moral judgments and commenting on one's society. But they tend to forget—or rather, to want not to see—that most of their heroes were very involved in the world in which they lived. To quote Pound's review of Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, "Flaubert pointed out that if

In this day of the anti-novel, of what John Barth calls "the literature of exhaustion" of Barth, Borges, Nabokov, Calvino, Barthleme, and Beckett, it has become very fashionable to say that literature has no relation to life whatsoever and so to absolve the writer of all moral responsibilities. Gass claimed the above writers as practitioners of his views, but he was wrong. Nabokov's Lolita is in part a comment on American attitudes toward love and sex. Beckett covers the human condition. Barth's The End of the Road is a critique of existentialism. By no means are these the only themes these writers are employing, but they must be considered.

Absurdism has a great deal to do with Gass' thinking; it is the motive behind his "less-real rooms" remark and his final statement, "What a loss," a deprecation of reality. The reality of existence lacks substance for him. As an artist in the process of creation, he feels his work of art is real, not the life in the streets. All artists feel this to a certain extent, but they must realize there is a world going on out there, because what is happening out in the streets is going to affect not only themselves, but those they love. Look at what happened to Thomas Mann, who had to flee Nazi Germany for fear of his life.

But what do you do when the snowman melts? After you have sacrificed all you have in order to construct your aesthetic fantasy world, what do you do when the mirage disappears? The question does not bother Gass. So everything is ruined when our imaginative construct is gone. "What a loss," he says. It is easy sarcasm which avoids the question posed.

But it is not surprising. To a man who asks that moral autonomy be awarded to physicists, philosophers, and poets, moral considerations are not especially important. To a man who asks us to renounce our "less-real rooms" for giant-snowman building, life is not real. Life is absurd. Life is a joke. So are war, poverty, bigotry, death, and evil. Ha ha. It is not surprising, but it is shocking.

Gass made an offhanded remark that was most revealing. He asked why artists should bother to improve "the scabrous body politic" since it has always been considered "scabrous." It is an easy thing for a white college professor to say in this country, at this time; we are the mightiest nation on earth, prosperous, physically isolated, relatively peaceful.

But it is a short memory that does not recall other times and places, even in this century, that were not scabrous but suppurating. Pick a place, any place. In this racist country alone, one-fifth of whose citizens live in poverty, we are only recovering from a hysterical period of assassinations, race riots, a decade of

Yet all the same, his attitude shows an alarming lack of concern for the quality of world our children will inherit. Artists and critics can have an influence on the life in the streets, but they are not going to attain it by sneering at "the sweaty standards" of the workaday world. And as for the human condition, which artists must report, because no one else will, with its interminable misery, waste, and violent death, with its constant loss of intangible qualities, both moral and personal, that can never be recovered, yes, it is a shame, it is a pity, it is a loss.

No comments:

Post a Comment