A stooge in the head is worth three cheers from the heart

by Nick Zegarac

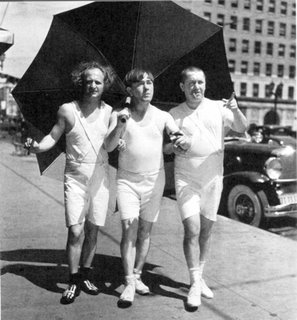

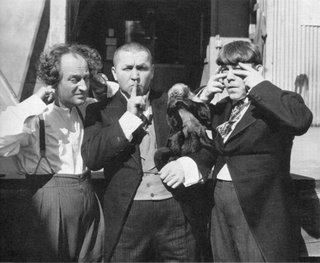

The Three Stooges are today regarded as cinematic icons; as American as apple pie, the undisputed masters of slapstick, and, as zanily unhinged as anything ever seen on the screen. If Laurel and Hardy were sublime punsters, the stooges were punch drunks. Pitted against the Marx Bros. leftist anti-establishment witty barbs, geared toward the anarchist intellectual, the stooges are low brow chuckleheads for the every man. Yet, the stooges have remained eternal – and arguably, have surpassed – their contemporary comedic legends. The endurance of one “nyuk-nyuk-nyuk” for example has managed to outlive almost all other filmed comedic bits of business put forth by rival acts, save radio hams cum film comedians Bud Abbott and Lou Costello’s ‘Who’s on First?’

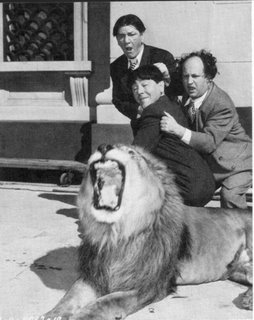

Who can forget the riotous boxing tournament, when Curly (the troupe’s most popular numb skull), after hearing ‘Pop Goes the Weasel’ manages to decimate not only his opponent in the ring but also his managers, Larry and Moe; or the moment when Curly, attempting to ‘fix’ a leaky bathtub, inadvertently builds a cage around himself from plumber’s tubing. Or Curly, with a large couch coil stuck to his rump, (the other end still attached to the couch), is pulled from his oafish female dancing partner at a  society party.

society party.

Curly: If her husband kills me, I'm comin' back to haunt you.

Moe: Haunt that house.

Curly: How many rooms?

Moe: Seven.

Curly: With bath?

Better still, the vignette in which Curly discovers a very feisty live oyster spewing projectile soup at him from his bowl of oyster stew. These, and many other moments, once seen are seared into the memory. Not bad for three guys with limited education who spent the bulk of their career appearing in two reel short subjects – rather than feature length films.

Woman - "I'm in a terrible dilemma."

Moe - "Yeah, I don't care much for these foreign cars either."

Professionally, it all began in 1908, when a feisty Moses (Moe) Harry Horwitz (then eleven) decided he had had enough with school and wanted to become an actor. There was one problem. Moses lacked even a glint of matinee idol good looks.

“Seeing my face in the mirror,” he would later recount, “covered with large jagged freckles…I would end up the ugly duckling of the Horwitz family.”

Still, he managed to finagle a gofer’s position at Brooklyn’s Vitagraph Studio on Avenue M in New York City. When asked by head of production Maurice Costello why he had consistently refused remuneration for his menial services Moses replied, “Because I’m looking for a job in films.” The ploy worked. Moses was cast in a string of bit parts for Vitagraph, including Van Dyke Brooks We Must Do Our Best (1909).

That same year, Moses (newly rechristened as ‘Moe’) met Ted Healy, the man who would amalgamate the stooges trademark humor before departing on other ventures. Healy was a bit of a drifter with greater aspirations for becoming a businessman than an entertainer. However, by 1912 Healy’s ambitions had shifted to Vaudeville and a modestly successful traveling troupe that included Moe and his brother Sam (Shemp).

The men appeared briefly in Annette Kellerman’s Diving Girls. Previously, Kellerman had made headlines for defying the odds of being stricken by polio at an early age, yet swimming the English Channel as a youth. Currently she was the star of an acquacade. But the Healy/Kellerman association ended abruptly after only one season when a contract diver fell to her death from the diver’s platform.

Still, Moe was determined. At sixteen, he lied his way into a stint aboard a traveling riverboat, The Sunflower for two seasons at a then plumb salary of $65 dollars a week. With his newfound strength as an actor, Moe reunited with Shemp for a blackface comedy relief routine: Howard & Howard – a study in black. Shemp’s draft into the armed forces briefly interrupted this lucrative venture, though afterward the two worked circuits for Loew’s and RKO until 1922. That was the year both men decided to marry; Moe to Helen Schonberger (the cousin of Harry Houdini) and Shemp to Gertrude Frank. But there was precious little time for romance.

A reunion with Ted Healy (and his wife Betty), paved the way for a new Vaudeville act – one that included aspiring comedian Larry Fine. The troupe also included the Haney Sisters – of which Larry would court and later marry the eldest, Mabel in 1927. At the outbreak of World War I, the act traveled the ardent route of playing small town venues. Larry attempted something of a breakout sketch ‘Fine and Dandy’ with a woman ironically named Winona Fine. The venture was extremely short lived. Back in the Healy fold, the act reopened as Ted Healy and his Three Southern Gentlemen, then later as Ted Healy and the Racketeers.

However, in 1927 Moe resigned himself to an official retirement from showbiz. His decision had been predicated on a deep seeded desire to prove his wife’s family – who had insisted that any marriage to an actor would never make for a stable home – wrong. After the birth of his daughter, Joan, Moe ventured into real estate.

The shift in profession proved disastrous. In an instant, his investment of $22,000 had dwindled to a meager $200.00. Another attempt at respectability, this time as the proprietor of a dried goods store, did little than to further strain the family’s financial status. Finally, Moe resigned himself to a reunion with Ted Healy – who had by this time become a rather prominent figure on the stage. The reunited group debuted in A Night In Venice (1929) – a comedic musical staged by Busby Berkeley.

A Night In Venice was a colossal success and paved the road to Hollywood in 1930 with a film offer from Fox Studios (then a precursor to 20th Century Fox). The film, Soup to Nuts (1930) was enough to convince Winnie Sheehan that the stooges were ready for the big time. However, a mere four days later the offer of a seven year contract was revoked, prompting Moe to make inquiries. What he discovered was that the contract had not included Ted Healy. Fearful that he was losing his own chance to score in films, Healy had confronted Sheehan with an impassioned plea not to sign the stooges as a solo. The rift generated between Moe and Healy was sufficient enough for the stooges to strike out on their own.

For the next several years, Healy and the new independent act of The Three Stooges (Moe, Shemp and Larry) struggled separately to find their niche. Both toured the theater circuit with their quiet animosity building. Another rupture occurred when Healy – ever more becoming a cynical drunk and embittered recluse – threatened to sue the stooges if they incorporated any bits of business from A Night in Venice into their new Vaudeville act. This pending lawsuit was settled quietly, but it did leave a bitter aftertaste for all concerned.

It was at this junction in their career that the success of Soup to Nuts began to pay off – with one caveat. It prompted more film offers to pour in but as the act Ted Healy and His Stooges. Reluctantly, the troupe reunited. However, while on tour for a live engagement at The Triangle Ball Room, Shemp received a solo film offer which Moe encouraged him to pursue. Outraged, Healy lamented that Shemp’s departure would ruin the act. But Moe had a winning replacement – his brother Jerome ‘Curly’ Howard.

With Curly in tow, Healy and the Stooges reunited on screen for Meet The Baron, Plane Nuts and Dancing Lady (all in 1933) but the partnership was from the start impossibly strained. After 1934’s cameo in Hollywood Party, Moe cornered Healy and his agent Paul Dempsey and officially broke their contract. Henceforth the new act would be known simply as ‘The Three Stooges.’