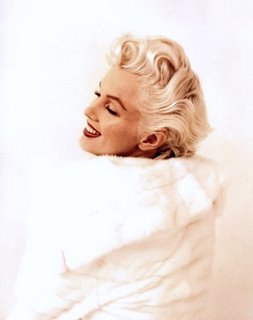

The Sad Unromantic Last Days of America’s Sex Goddess

The Sad Unromantic Last Days of America’s Sex Goddess“Bear in mind that the myth of Hollywood is far less than the reality!” – David Brown

It was a project begun in earnest, arguably in haste and with high expectations that ended in the tragic death of one of America’s best known and most beloved stars – Marilyn Monroe. By 1962, Monroe was 20th Century-Fox’s most bankable commodity since Shirley Temple; a troubled (some might say, troublesome) woman who’s familial past was littered in untidy demons that plagued the actress throughout her life.

George Cukor’s Something’s Gotta Give (1962) was to have been Marilyn Monroe’s 30th film – a landmark by anniversary standards. It was a remake of My Favorite Wife – a quaint Cary Grant/Irene Dunne screwball comedy from the 1940s about a woman who returns to her husband and children after missing, and presumed dead for almost five years. Monroe - who would turn 36 during the shoot; a prelude of the waning years in which that sex goddess persona she had so carefully crafted and maintained would undoubtedly have to yield to the aging process – perceived her role as a departure from the typical resident ditzy blondes she had played in the past.

To say that the final days of Marilyn Monroe were isolated and tragic is a foregone conclusion in retrospect – though few apart from director, George Cukor recognized the extent to which Monroe’s insular cocoon had damaged her own reputation, fragile ego and her ability to relate to anyone outside of a select fair-weather flock that included acting coach Paula Strasberg and publicist Pat Newcomb. “I don’t think they helped her at all” producer Henry Weinstein offered in a retrospective interview, “I think they just pumped her up so that they could use her.”

Monroe, who by this time had spent seven years under the tutelage of ‘method’ coaches Lee and Paula Strasberg at the Actor’s Studio in New York and, in that same interim had developed the dangerous habit of combining champagne with sleeping pills, had cultivated a legendary reputation for tardiness and costly delays. In an attempt to expand her range of authority and creative control, the actress had also founded Marilyn Monroe Productions in 1955: the result - Something’s Gotta Give would be co-produced by Marilyn and 20th Century-Fox. The joint venture also gave Marilyn director and script approval.

George Cukor, who had previously worked with Marilyn on the bombastic but abysmal Let’s Make Love (1960) reluctantly agreed to reunite with her on this project, but he quickly regretted his decision. Executive David Brown had initially proposed the project before being unceremoniously deposed in a backstage coup and replaced by producer, Henry Weinstein. The turn of events that removed Brown from the project had begun with the installation of Marilyn’s psychoanalyst Dr. Ralph Greenson and his friendship with Weinstein. Greenson convinced Fox studio brass that to surround Marilyn with close ‘friends’ could only help to bolster her spirits and contain her insecurities. Undoubtedly, the top brass agreed, though Cukor was forever bitter over Brown’s replacement – a friction that Weinstein seemed to deliberately exacerbate by leaving the director out of script supervision meetings.

For his part, Cukor’s initial attempts to maintain peace and order on the set, while at the same time coddling Monroe’s ego, was genuine. On this latter score he was greatly and inadvertently aided by Weinstein’s patience with Monroe – serving as the thankless go between Cukor and Paula Strasberg, whom Cukor absolutely despised. After Let’s Make Love, Cukor was well acquainted with Marilyn’s chronic illnesses and inability to work under any sort of schedule.

However, Weinstein was shocked and appalled when, after having screened Monroe’s luminous costume tests, he arrived at her Brentwood home for a consultation to find her sprawled out on her bed, nude and unconscious from an apparent overdoes of sleeping pills. Imploring the studio to suspend the project for at least one month, Weinstein’s pleas were rejected on the basis that the studio could not afford any more costly delays (Fox was, at this time, hemorrhaging money on the far off Italian shoot of Cleopatra, a film with its own litany of difficulties).

Instead, Cukor moved ahead with preproduction on the project. An exact replica of the director’s Brentwood Hills home was built by designer Gene Allen on a Fox sound stage and served as the film’s primary location for principle photography. The set also became a point of interest for the Shah and Empress of Iran while on their goodwill tour. Although most of Hollywood turned out – understandably agog – to meet royalty, Marilyn remained conspicuously absent from the fray. Her official excuse given to Weinstein was that she did not approve of the Shah’s anti-Israel policies. However, at the time of the Shah’s visit, Monroe had already been absent from the project for nearly a week, with varying claims to ill health brought on by acute sinusitis, the flu and a respiratory infection.

Monroe’s tardiness was only one reason why the project had fallen behind. Even before a single strip of film had been shot, Something’s Gotta Give veered $300,000 over budget on script rewrites alone. Beginning with a draft by Arnold Schulman (that Cukor found unsatisfactory), then another by Nunnally Johnson (who had crafted the Monroe mega hit, How To Marry A Millionaire 1953), and finally with writing credit exclusively assigned to Walter Bernstein, the project seemed plagued by setbacks from the start.

Eventually, a quiet rift developed on the set with loyalties divided between Cukor and those backing Henry Weinstein. Though Cukor tried his best to keep some semblance of a united front, his faith in the project and attempts at harmony were increasingly being thwarted by Monroe’s failure to show up on the set. Working around Marilyn’s absences, Cukor eventually reached a stalemate in which shooting could no longer progress without the actress’ involvement.

Though Dr. Greenson and Marilyn’s regular physician, Dr. Hyman Engelberg attempted to ply the actress with various medications and almost daily psychiatric counseling, her work ethic worsened. On April 23rd, 1962 Marilyn was granted a one week retreat at the Actor’s Studio – a move that invigorated her resolve for the project, but infuriated Cukor when she arrived at Fox with Paula Strasberg in tow.

Strasberg’s reputation for undercutting directorial authority was well entrenched in Cukor’s recent memory. Her involvement with Marilyn on the set of Something’s Gotta Give proved no exception. Originally, Monroe had sought out the Strasbergs to gain respect and credibility for her craft, releasing a statement to the press, that her greatest goal was to become “a good actress” – rather than a joke, which she believed was Hollywood’s current impression of her acting prowess. Yet, if the actress was dedicated to improving her thespian talents, her personal life was exemplified by manic bouts of desperation that made her emotions spin out of control.

Haunted by childhood memories of her biological father’s rejection and a mother whose revolving door inside various mental institutions had begun to mirror her own instabilities, Monroe’s private life traveled the dark roads paved with failed marriages, botched abortions and rumors of torrid liaisons between the President of the United States and his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy. All of these personal failures and anxieties were undoubtedly exacerbated by Henry Weinstein’s sudden revocation of Marilyn’s pre-arranged time off to attend the Kennedy inaugural in New York. Defiant, and perhaps self-assured that her place at Fox was secure, Monroe renounced both her producer’s wishes, and the studio’s edict to perform the now legendary, Happy Birthday Mr. President.

The pall cast by this gesture was sufficient enough to turn the tide of concern for Marilyn’s health against her. Interoffice memos that had once stated cancellations due to “ill health” were revised to read “due to Miss Monroe’s failure to show up” on any delay incurred afterward. Perhaps more than anyone else on the set, George Cukor regarded this latest episode as a personal betrayal. Until then, he had been Marilyn’s greatest champion on the set – bolstering the morale and ever-convincing cast and crew that the final on camera results would counterbalance whatever animosity had been incurred.

But even Cukor was ready to forgive his star when on May 23rd she appeared healthy and happy to shoot her nude scene in the swimming pool – the first ever attempted by a major Hollywood star. Taking advantage of the paparazzi, Monroe discarded her flesh-colored body suit midway through the shoot in a bit of playful exposition that quickly turned into a public relations feeding frenzy. She appeared as the top story on all the national and international film magazines.

After viewing select footage of the sequence, Fox executives were equally ecstatic. Their euphoria however was short lived. On Friday, May 25th Marilyn unexpectedly left Fox and for all intensive purposes disappeared for the weekend, emerging from her private escapade on the following Monday as an emotional wreck, and with yet another health excuse not to show up for work. Her stalemate lasted three days.

In the final few days that remained between the time Marilyn returned to the set on June 1st to celebrate her birthday and June 4th, the day both Cukor and costar Dean Martin had decided they had had enough of being manipulated, Marilyn’s psychiatrist, Dr. Greenson begged the front offices not to fire Monroe from the project. However, on June 6th, in a rare outburst for which he had not been known, Cukor openly expressed his frustrations to gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, even going so far as to renounce his star and make the assessment that her career in Hollywood was officially over. On June 8th 1962, Fox concurred with Cukor’s spur of the moment. They fired Marilyn from Something’s Gotta Give.

However, when Fox announced that other stars were being considered from the project, including Kim Novak and Lee Remick (who had actually been fitted in Marilyn’s costumes), Dean Martin effectively pulled the plug on the project by pointing out that contractually he had costar approval. Martin’s final edict stood – no Marilyn/no movie. On June 11th 104 contract workers were given their pink slips and the production closed down for good.

To her credit, Marilyn’s initiative and resolve were inspired. Squeezed to the point of extinction by the press coverage she had been receiving, Marilyn launched into a one woman media blitz that she hoped would resurrect not only her reputation but the film. Providing indiscriminate interviews to anyone who would listen, Marilyn also allowed photographer George Barris unprecedented access, and gave an exclusive to Life reporter Richard Meryman, whom she quietly implored “please, don’t make me look like a joke.”

The joke…it seems…was to be on the rest of the world. For on Saturday August 4th Marilyn politely turned down a dinner invitation extended by Pat and Peter Lawford in favor of a quiet evening at home with her housekeeper, Eunice Murray. What occurred at that Brentwood home thereafter remains a mystery. Though conspiracy theorists have placed everyone from the mafia to Robert and John Kennedy at the scene during those final fateful hours – one certainty is indisputable: Marilyn Monroe was dead. An autopsy revealed large quantities of Seconol and Chloral Hydrate in her system – neither prescribed by either Greenson or Engelberg. A distraught Joe DiMaggio arranged for her Forrest Lawn burial – a quiet gathering that excluded all of Marilyn’s Hollywood entourage. For decades thereafter, the former baseball great would replenish Marilyn’s vault marker with fresh flowers.

In the interim, Marilyn Monroe, the actress, has transcended mere stardom. Her iconography is more galvanic and resilient today than at the time of her death. She is arguably the most glamorous star to emerge from post-war American films, and the patron saint for all the scarred and tragic Hollywood horror stories that had gone before her and have come to light since.

In 1995, 20th Century-Fox finally edited the 500 minutes of raw Cinemascope footage that Cukor shot into a reconstruction of Something’s Gotta Give. Although incomplete, the film as it is remains a final glimpse into the psyche of Marilyn Monroe – unfortunate star and mischievous woman who so readily found her self-worth miscast in the persona she had helped to create; one that ultimately consumed her in the end.

What is past is prologue. The legacy of Marilyn Monroe lives on.

@Nick Zegarac 2006 (all rights reserved).

No comments:

Post a Comment